По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

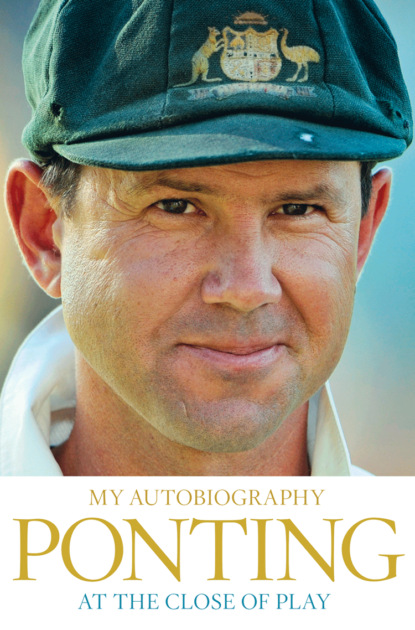

At the Close of Play

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The short stuff would continue throughout the Test series, but just as the boys had promised they stood up to every single bumper, while our pace attack, spearheaded by Glenn McGrath, gave at least as good as we received. The way Pigeon took them on was magnificent and the positive body language of all the boys was so impressive — it seemed to intimidate the West Indies players, which was almost stunning given the manner in which they’d steamrollered all challengers over the previous 15 years or more. When we won the Frank Worrell Trophy in Jamaica our dressing room was filled with TV cameras and reporters and they were allowed to stay to do their interviews while the room was doused in beer and champagne and some of the worst renditions of Cold Chisel’s ‘Khe Sanh’ ever heard were telecast via satellite back to Australia. Eventually, though, everyone except those in or very close to the team were asked to leave, we formed a tight circle, and Boonie led us in a rendition of our anthem that literally had the hairs on the back of my neck standing to attention. Even though I didn’t play in the series I still felt part of it all. In the years that followed, there would be some rousing renditions of ‘Underneath the Southern Cross’— I’d even get to lead the team in a few — but I’m not sure any had the raw emotion of this one.

That night, we ended up at a hotel next door to the one where we were staying, but most of the guys stayed in their whites and along with a few past players — Allan Border, Dean Jones, Geoff Lawson and David Hookes — who had been savaged by the West Indies in the past, we sat on deck chairs, glasses never empty, and talked about how good it was to win. I hardly said a word, just took it all in. In the years that followed, all the senior guys on this tour would talk about how their memories of the losses they suffered in the 1980s and early 1990s acted as a spur to keep going when the team started winning consistently; how it taught them to be relentless. Coming later as I did, I never experienced those painful setbacks, but I saw how much winning in the Windies in 1995 meant to the older guys. It was a lesson I never forgot.

THE TWO MONTHS WAS an education for me in other ways, too. Rooming with Steve Waugh, for example, meant I could grill him on how he approached Test cricket. Tugga was a cricketer who had thought deeply about the mental challenges of batting against giants like Ambrose and Walsh, and he was also happy to talk about his struggles at the start of his international career, like how he coped with not scoring his first Test hundred until his 27th Test. It wasn’t that he was trying to scare me; more that he wanted to stress that success wasn’t going to come easily. If I persisted, he explained, I was a chance for a long career.

After Steve, I ‘bunked’ with Tim May, which was a completely different assignment. Maysie was not in the Test XI and had made the assessment that with the team going well that situation was unlikely to change, so he set out to enjoy the tour as much as possible. What was most remarkable was his rare ability to turn up at breakfast seemingly as bright as a button despite the fact he’d been out until sunrise. He knew there were boundaries and he never crossed them, and rather than get people into trouble his natural instinct was to make sure everyone was sweet. When I said at midnight I’d had enough for the night, Maysie never talked me into kicking on (which, more than once, he easily could have), because he was always in my corner. He is also a born comedian, and remarkably astute at mimicking people and exposing their foibles, which meant that sharing a room with him was a laugh a minute.

As well as a couple of days at the races, the odd spot of deep-sea fishing and a few rounds of golf (especially in Bermuda), there were numerous activities organised by the team’s social committee. These ranged from team dinners to beach volleyball to, at the start of the tour, a facial hair–growing competition, where we were given a specific assignment — handle-bar moustache, bushy sideburns and so on — with prizes to be awarded to the best achievers. I was assigned a goatee beard. Apparently, this competition had been a bit of a hit on the Pakistan tour in 1994. This time, however, the guys quickly lost interest, but I kept at it, mainly because I copped such a ribbing during my slow early progress that I was determined to see the thing through. In the end the goatee stayed with me for the best part of the next two years.

In Guyana, where we played the final one-day international of the tour and the first of two first-class games before the first Test, I got my ear pierced, which seemed like a good idea at the time. Dad had always told me if I came home with an earring he’d rip it straight out, and to this day I wonder why he didn’t. Maybe the fact Boonie got his ear done at the same time had something to do with it, but it didn’t last too long. Another way I confirmed my novice status on this tour came after we were told not to stay on the phone if we called loved ones in Australia. I made a couple of calls home to Mum, kept talking, and was horrified to discover when we checked out of the hotel that I was hundreds of dollars out of pocket.

When we arrived in Bermuda at the tour’s end, the boys were ready to party. We hadn’t been at our flash resort for long and I was down at the bar with a trio of seasoned campaigners — Boonie, Tubby and Errol Alcott — and after a couple of ales someone proposed we check the island out on the mopeds that were available for guests to use. We didn’t get far before we lost Boonie. First, we decided to give him a chance to catch up, but when he didn’t reappear we figured we should go back and look for him, and when we couldn’t find him we assumed he’d returned to the bar. That seemed like a good idea so back we went. But he wasn’t there either. What to do? We ordered a beer, having decided that if he didn’t return by the time the drinks were finished we’d organise a search party, and it had reached the stage where that’s what we were going to do when our hero finally emerged with blood seeping from cuts to his legs, arm and chin and an unlit cigarette perched precariously on his bottom lip.

It was one of those situations where everyone wanted to ask, ‘What happened to you?’ But everyone was waiting for everyone else to ask that obvious question. Then, before anyone said anything, Boonie quietly deadpanned, ‘Anyone got a light?’

He’d been riding at the back of our pack when he failed to take a turn at high speed and he and bike parted company.

Perhaps his mishap should have been a warning, but there was no holding back when a larger group of us went out that night for some more exploring. This time, Ian Healy stalled his moped and I volunteered, because of the basic mechanics Dad had taught me, to get it restarted, saying, ‘Don’t worry, I’ll catch you all up.’ I was able to do that, but then the bludger conked out again on the way back to the hotel and as I tried to get it going the back wheel got caught in a gutter. My response — part bravado, part frustration, part eagerness to return to the pack — was to go full-throttle, and when the bike did free itself it took off on me straight into a pole on the opposite side of the road. I’m not quite sure how I survived, but the bike was a write-off.

This wasn’t the only time a moped took a battering while we were in Bermuda. Right at the start, we had to get a permit before we could ride the things, which involved a basic test in the resort car park. A number of the guys had their partners with them for this final leg of the tour — until then, it had been boys only — and the girls had queued up so they could ride around the island too. All each of us had to do was go in a straight line, ride around a tree situated on the edge of the bitumen, and then come back, dodging a couple of witches’ hats along the way. I passed the course easily, we all did, except for one of the girls who had no idea how to ride a bike and when she was supposed to slow and turn instead she panicked and accelerated straight up a steep rise behind the tree. Near the top of the rise, the bike flipped back over itself while she kept hanging on, and for a moment it looked like things might turn really messy. Fortunately — and a bit miraculously — she survived, but then, when she picked up the bike, the back wheel was still spinning and as soon as it hit the ground it took off again. The two of them — bike and terrified rider — shot straight across the car park and it was a miracle (again) that she was finally able to get the thing to stop. Despite all this, she was then given a pass and soon we were on our way.

STRICTLY SPEAKING, I SHOULDN’T have been given a permit, because when we were making our applications we were required to fill out a form, and one of the questions was: Do you have a driver’s licence? The correct answer — if I wanted a permit — was ‘yes’, so I had to lie.

I could have got my driver’s licence any time after I turned 17, but I never felt like I needed one, at least not until I was well into my 20s. From the time I first went to the Academy when I was 15 I was never really in one place for any length of time, so getting an opportunity to do the lessons was tricky. And when I was back in Launceston, there was usually someone able to give me a lift and more often than not at other times I could get to where I needed to go without too much of a hassle. It’s not that big a town. Most of the time I was going no further than the golf course, the cricket ground, the footy or the dogs, and I was rarely going to any of those places on my own.

I certainly wasn’t scared of driving, more just lazy, I guess. If I’d found myself constantly marooned at home unable to get to places I needed to go, I’m sure I would have got my licence in record time, but the blokes I spent my time with were all happy to pick me up or Mum or Dad were usually there if I needed a lift. And if you arrived at the club on time there was a bus to take you to the away games. Ironically, one of my first sponsors was Launceston Motors, the city’s biggest Holden dealership, and they offered me a car as part of the deal. (Perhaps my favourite sponsorship from those early days was with a local bakery. I didn’t get anything out of it; instead the funds were used to renovate the clubhouse at Invermay Park.)

When I was 24 I bought a house in Norwood, a suburb in South Launceston, which I shared with my then girlfriend. It was after we broke up early in the 1999–2000 season — and I found myself living in the house on my own — that I finally felt the need to get my L plates.

I suppose I can tell the story of finally getting my licence now. There was a policeman in a small town about three hours’ drive from Launceston on the north-west coast who may not have been the strictest when it came to those sorts of things. I don’t know how I heard of him, but Mum drove me up there and I basically went for a little drive with him and before I knew it I was a registered driver. If Boonie ever needed a lift all he had to do was call.

SIX WEEKS AFTER WE returned home from the West Indies in 1995, I was in England as a member of a ‘Young Australia’ team that was captained by Stuart Law. With hindsight, it’s easy to say that this was a classy outfit — of the 14 guys in the squad, four had already played Test cricket (Jo Angel, Justin Langer, Matthew Hayden and Peter McIntyre) and eight more of us would before our careers were over (Stuart Law, Matthew Elliott, Michael Kasprowicz, Shaun Young, Adam Gilchrist, Martin Love, Brad Williams and me). The only blokes who didn’t go on to win a baggy green cap were the South Australian pacemen Shane George and Mark Harrity, but if you’d told me at the time that they would be the two to miss out, I wouldn’t have believed you. They were two excellent quicks.

We were reminded in our first team meeting that an Ashes series would be played in the UK in 1997, so the guys who did well in English conditions on this trip might gain some inside running. To be honest, though, while some blokes might have been planning that far ahead, I think for batsmen like Haydos and Lang, who’d experienced Test cricket, and myself and Stuart Law, who had played ODI cricket in the previous 12 months, we were hoping to crack the top side before the middle of 1997. The problem was, given that the Frank Worrell Trophy was now in the Australian Cricket Board’s trophy cabinet, there didn’t seem to be an opening. All we could do was make a case to be next in line, and that process began with this tour.

In this regard, I didn’t do myself any harm, going past 50 five times in 12 first-class innings, but the other blokes had a good time of it as well, so I never felt as if I was standing out. A highlight for me came at Worcester, when I scored 103 not out against an attack that included the former Test bowler Neal Radford, but the enormity of the task I faced to make the Test side was underlined in our one-dayer against Surrey at the Oval, when I thought I batted really well to score 71 from 87 balls. Trouble was, at the other end Stuart Law was in sensational form, smashing 163 from just 126 deliveries and in the process making everyone forget I was even out there. There were numerous examples of this happening, where one guy would play really well but another would do something even better. Against Somerset, for example, Shaun Young made an excellent hundred, but Adam Gilchrist hit 122 from 102 balls, reaching his ton with a colossal six. The competitiveness among us would serve us and Australian cricket well for the following decade.

The only downer of the tour for me was that in the six weeks I was in England I never once had the chance to get to a dog track or a racecourse. Sure, I got to see iconic tourist attractions like Buckingham Palace and the Houses of Parliament, and to play at famous grounds like the Oval, Headingley and Edgbaston, but a number of blokes back in Launceston had told me how different and interesting horse and greyhound racing can be in Britain and I wanted to experience it for myself. All I could do, as I tried to find some sleep on the long flight home, was to make a commitment to do all I could to get back to England in the near future, preferably with the blokes I’d been with in the Caribbean, this time as a member of an Australian Ashes touring team.

Practice makes perfect is one of those everyday coaching lines that you hear all the time. But for me it goes one step further than that — perfect practice makes perfect! You have to train as specifically as you can for what you require and do it at an intensity that is as close as possible to match conditions.

For me, cricket has a long way to go to replicate this specific training. We train away from the centre wicket and outfields — on surfaces that are nothing like what we play on during a match. As a batsman preparing in the nets, you are at the end of a wicket that is almost certainly nothing like the centre wicket for the game. You face four or five bowlers — all of different paces and techniques — bowling in an order one after the other with different balls. Again, nothing like what happens in a game, when you face the same bowler with the same ball — for six balls in a row. Bowlers are faced with similar challenges. Many of them are unable to train with their full run-ups, with a full set of different balls to replicate different times in a game, no field placements to bowl to, and most bowlers are limited to the number of balls they will bowl in training to protect their capacity for a game.

I had a saying ‘train hard and play easy’ that summed up the need for more specific training. I think this was one of the reasons we weren’t at our best in the 2005 Ashes series, where we lacked the specific training we required. We certainly fixed that for the 2006–07 Ashes series, where I demanded that Brett Lee, Glenn McGrath and Jason Gillespie bowl new balls at full pace at me in the nets, day in and day out. The bouncers, movement and sheer intensity of those training sessions helped us all and was a part of the foundation for our 5–0 whitewash of England in that series.

Fielding practice has certainly come a long way since my early days in cricket and it’s as specific today as ever. Most days you now get on the outfield of the ground you are playing on. You can replicate a whole range of typical game situations from catching to runs-outs and throws. I had a set routine as part of my one-day training, where I had someone hit balls to me at backward point or extra cover, and I would field the ball and get it into the stumps as quickly as possible. I also had a variation of this where I would attempt to throw down the stumps at either end of the ground. I did tens of thousands of repetitions of this, at high intensity, and it certainly was perfect practice that made perfect.

(#ulink_cb012850-2030-5835-a0d1-5c57343de23d)

AT THE START of the 1995–96 season, Justin Langer and I were at the front of the queue to get into the Australian Test team if an opportunity came up, but Stuey Law was one of a number of gifted batsmen who were close behind. Of all of us, he was the one who started the season best in the early Shield and Mercantile Mutual one-day games. Then in early November, I finally found some form in a Shield game at Bellerive against Stuey’s Queensland, scoring 100 and 118, but he replied with a stylish 107 in their second innings. At the same time, poor Lang could hardly score a run for WA, until he cracked a second-innings 153 in Adelaide.

It was that old, quiet battle again, all the fringe players pushing each other.

Australia was involved in three Tests against Pakistan, and as that series unfolded concerns grew about the form of the Australian batting order, with most attention being on David Boon and Greg Blewett, who were struggling. In the third Test, which Pakistan won by 74 runs, Boonie and Blewey both missed out, while at the same time I made some big runs against the touring Sri Lanka, whose three-Test series against Australia was due to begin at the WACA on December 8. First, I scored 99 in a one-dayer at Devonport and then 131 not out in Tasmania’s first innings of a four-day game against the tourists at the NTCA ground in Launceston with Test selector Jim Higgs watching. I was a little lucky, to be honest, as I had been dropped on 14. The media believed Blewey was gone for the opening Test against the Sri Lankans, and I was the obvious option to take his place. Then it was announced that Steve Waugh was out because of a groin strain, which seemed to make my selection even more likely.

THE DAY BEFORE THE TEAM was announced, the Examiner ran a back-page headline which shouted: ‘Pick Ponting!’ Inside, it pointed out that if I was selected it would be the ‘best 21st birthday present he could wish for’, because the Test was due to start on December 8, which was 11 days before I would turn 21. The next day, the front-page banner headline was more exuberant: ‘He’s Ricky Ponting, he’s ours … and HE’S MADE IT!’

Underneath was a big photograph of me giving Mum a kiss, while the accompanying story began: ‘Tears of pride welled in Lorraine Ponting’s eyes yesterday as she told of how her son Ricky had always said he would play Test cricket for Australia.’

The Test side was named on the last day of Tassie’s game against Sri Lanka, and that photo of Mum and me was snapped just before the news was announced over the PA system at the NTCA ground. There was something a bit special about learning of my promotion at my home ground with family, some of our closest friends and my Shield team-mates there to share the moment with me. Mum was never keen to watch me play — after I failed a couple of times when she was there, she started thinking her presence might be the cause — so when I saw her in the grandstand when I walked off the field I figured something must have been up. She ran down to meet me at the gate and was the first to tell me I’d been picked for Perth along with Stuart Law. It would be Stuey’s first Test as well.

Unfortunately, Dad was working, rolling the pitch at Scotch Oakburn College (Ian Young had teed up that groundsman job for him), but we caught up at home that evening and then, when the phone finally stopped ringing for a minute, the whole family dashed out for a celebratory dinner. After that, I raced over to the greyhound meeting at White City, where I met up with a few mates. It wasn’t a late night, but it was a beauty — everyone at the track seemed to know that Tasmania had produced another Test cricketer and I was overwhelmed by the number of people who came up to wish me all the best.

Inevitably, there were plenty of well-meaning individuals who wanted to give me advice. I’m not sure who suggested I get a haircut (probably Mum), but I did as I was told. Of all the suggestions offered, a couple stand out, not so much because of the advice offered but who was giving it: Uncle Greg told me to ‘stick to what you know best’ and then David Boon said I should just ‘go out there and enjoy it’. Nothing more complicated than that. Not long after I landed in Perth, captain Mark Taylor reminded me I was a naturally aggressive batsman and fielder. ‘I want you to add some spice to the side,’ he said. ‘And don’t go away from the style of cricket that got you into the team. It’s worked for you in the past and it will work for you here.’

I was actually one of three newcomers, with Michael Kasprowicz (for the injured Paul Reiffel) also coming into the 12-man squad, the likelihood being that Kasper would be 12th man, with me batting at five, one place lower than I’d been batting for Tasmania, and Stuart Law at six.

We flew to Perth on the Tuesday, three days before the Test was due to begin, but I honestly can’t remember feeling particularly nervous, at least until the day of the game. I guess the fact I’d been with the guys in New Zealand and the West Indies helped me, plus the fact that I’d also come into contact with a number of the players at the Academy, or with the Australia A team in 1994–95 or on the Young Australia tour. It’s funny thinking back, but while my memories of the actual game remain strong I recall very little of the build-up — except for my constant modelling of my very own baggy green cap in front of the mirror and the fact I took the stickers off my bats, sanded the blades down and then re-stickered them all and put new grips on the handles. I also knew the occasion was special because my parents, as well as Nan and Uncle John (Mum’s brother) and Aunt Anna Campbell flew over. Since he retired from cricket, I could count on two hands the number of times Dad had given up his Saturday golf to watch me play, and he’s never been a bloke to move too far away from his comfort zone unless he has a good reason to, but here he was in Perth, a long, long way from home. Pop, however, was too set in his ways to fly all the way to Western Australia.

I do remember going out and buying an alarm clock, to complement the clock-radio next to my bed at the hotel, and the two wake-up calls I organised and the early-morning call from Mum and Dad, all to make sure I wasn’t late for a day’s play. No way was I earning the wrath of Boonie or Shippy again.

HAVING SAFELY GOT TO the ground on time, we bowled first after Tubby lost the toss, which gave me a day to ‘settle in’ and also meant I could prove that, as a fielder at least, Test cricket was not going to be a problem for me. More often that not in those days, almost as a rite of initiation, the youngest member of a Shield or Test team became the short-leg specialist (rarely a favourite fielding position for cricketers at any level), and I’d fielded there a few times for Tasmania in the previous couple of years, but Boonie had made that position his own for the Australian team, so I was allowed to patrol the covers, which gave me a chance to burn off some of the nervous energy that was surging through me.

On day two, Michael Slater scored a big century, he and Mark Taylor added 228 before our first wicket fell, not long before tea. I went looking for my box and thigh pad. Boonie was controversially given out just before the drinks break in the last session, so I went and quickly put my pads on and then, as the last hour was played out, I grew more and more fidgety, going to the toilet more than once but never for long. Out in the middle, Slats and Mark Waugh looked rock solid on what had become a perfect batting wicket, while Tubby saw I was getting very edgy, to the point that 10 or 15 minutes before stumps he asked Ian Healy to pad up as nightwatchman if a wicket unexpectedly fell. The move proved unnecessary; my first Test innings would have to wait another day.

I was shattered when I got back to our hotel — it had been a long day, even though I’d never got a chance to bat. (I always found it very difficult having to wait so long to have a hit, and didn’t have much practice at it as I rarely batted as low as No. 5 in a first-class game; having to adjust to sometimes waiting around for ages before I got a bat was one of the hardest things I had to do in my early days as a Test cricketer.) I went out for dinner that night with Mum and Dad, and in their company I felt reasonably relaxed. My sister Renee had called from home to say she had scored 48 Stableford points while playing for Mowbray Golf Club against Devonport GC in a competition known as the ‘Church Cup’ — a colossal effort which would take three shots from her handicap — and it appeared our parents were just as proud about her achievement as they were in me playing a Test match. Mum insisted on an early night, but when I went to bed there was no way I could get to sleep. The strange thing was that whereas in the days leading up to the game I’d been picturing myself doing something positive, playing a big shot, even making a hundred, now I was a fatalist — picturing myself getting out for a duck, run out without facing a ball, or maybe I wouldn’t get a bat at all, then get left out of the side when Tugga came back and never play for Australia again. When I woke the next morning I felt as if I hadn’t slept a minute, but at the ground I was a lot calmer than I’d been the previous evening and I hit the ball pretty well in the nets before play.

Slats was 189 not out at the start of the day, and there was some talk among the team about him having a shot at Brian Lara’s then world record Test score of 375, but in the first hour, totally out of the blue, he drove at Sri Lanka’s spinner Muttiah Muralitharan and hit an easy catch straight back to the bowler. Just like that, he was out for 219, Australia 3–422.

I DON’T REMEMBER WALKING out to bat, taking guard or talking to my batting partner, Mark Waugh, before I faced my opening delivery. However, I do recall that from early in my innings I was batting in my cap (rather than a helmet) and I will never forget the first ball I faced in Test cricket … a well-flighted delivery from ‘Murali’ that did me fractionally for length as I moved down the wicket. I pushed firmly at the ball but it held its line and clipped the outside edge of my bat … and for a fateful second I thought my Test career might be over as soon as it had begun. Fortunately, I’d got just enough bat on it for it to shoot past first slip’s hand and down to the fence for four, which took away the possibility of a duck on debut and slowed my heartbeat a little. In fact, it calmed me down a lot — it doesn’t matter whether you’re batting in a Test match or in the park, if you nick your first delivery and it goes to the boundary you feel lucky, like it might be your day.

For the next four hours, it looked like it was going to be mine.

Initially, I was a little scratchy, but then they dropped one short at me and I belted it through mid-wicket for four. Middling that pull shot was what I needed; it was as if I shifted into a higher gear. From that point on, my feet moved naturally into position, I had time to play my strokes and my shot selection was usually on the money. I’d batted at the WACA a couple of times before and loved the extra bounce in the wicket and the way the ball came on to the bat, and the light, too, which seems to make the ball easy to pick up. All I focused on was ‘watching the ball’, a mantra I repeated to myself before every delivery, the way Ian Young had told me to do. Being out there with Mark, who always made batting look easy and was a brilliant judge of a run, helped me enormously and then, when he was out for 111 to make our score 4–496 Stuart Law came out. Two of us out there in our first Test. He started very nervously, which in a slightly weird way was good for me as well, because suddenly I felt like the senior partner instead of the rookie.

When I reached my half-century, I looked straight away for my family in the crowd, especially for Mum, and I pointed my Kookaburra in her direction. It was a very satisfying feeling getting to fifty, because I knew — even with Steve Waugh coming back into the team and Stuey now looking comfortable — that I’d get another game. Now, I just wanted to enjoy it. We were already more than 200 in front, so I knew a declaration was coming sooner or later, certainly before stumps, but Tubby never sent a message saying I had a set amount of time to try to get a hundred. So we just kept going.

It was only when I moved into the 80s that I really thought the ton was on. By that point, the way Stuey and I were going through the last session of the day, he’d get to a half-century and I’d make three figures about half an hour before stumps, and that seemed a logical time for a closure. But it wasn’t to be. Sri Lanka had just taken the third new ball and I was on 96 when left-arm paceman Chaminda Vaas got one to cut back and hit me above my back pad — closer to my knee than groin. They did appeal, quite loudly considering how much it had bounced and the state of play, while I panicked for that split-second after I was hit (as a batsman always does as a reflex when hit on the leg anywhere near the stumps), but I quickly calmed down when I realised the ball was clearing the stumps. Nothing to worry about.

Then, Khizar Hayat, the umpire from Pakistan, gave me out lbw.

I simply couldn’t believe it. I looked down at the ground, fought the urge to complain or kick the ground, and began to trudge slowly off. What else can I do? The Sri Lankan captain, Arjuna Ranatunga, rubbed me on the head, as if I was a kid who’d just been told to go inside and do some homework, and for a moment I felt a surge of anger, but I managed to let his gesture go. I felt so empty, a feeling accentuated by the mass sigh and stony silence that immediately greeted the decision, though the crowd was very generous in their applause as I approached the dressing room. You only get one shot at scoring a century in your first Test innings and I’d done the hard work … and that opportunity had been snatched away from me when everyone, me included, thought I was home. Apparently sections of the crowd got stuck into the umpire, but I didn’t hear it. All I could think of was the hundred that got away.

Tubby declared immediately, with Stuey left at 54 not out, which meant that there was plenty of activity in the room as we prepared to go out for the final four overs of the day. There was still time for the boys to congratulate me on how I’d played and to tell me I’d been ‘ripped off’, a fact that was confirmed for me as I watched the replay of my dismissal on the television in our room. I was gutted. I felt like I’d got a duck, like everything I’d done was a waste. Back on the field, the fans were now really giving it to umpire Hayat, and this time I heard every crack, from the obvious to the cruel.

Umpiring mistakes, as much as your own, can cost you records and matches, and this one cost me the chance to join that very exclusive club of Australians who have made a century in their debut Test innings. I guess there were extenuating circumstances; it was a really tough Test match. Hayat had been out on the field for five-and-a-half hours on a very hot day, and he was under pressure after reporting the Sri Lankans for ball tampering and then giving David Boon out when he shouldn’t have earlier in the Test. Making it worse, we went out and bowled four overs, and in the last over of the day I was fielding bat-pad on the offside for Shane Warne, and Warnie got a ball to fizz off the pitch, straight into the middle of the batsman’s glove and it popped straight up to me. All I had to do was catch it and throw it jubilantly up in the air, which I triumphantly did, but umpire Hayat said, ‘Not out.’

Afterwards, I said all the things they expected me to say: that I would have taken 96 if you’d have offered it to me at the start of the Test; that good and bad decisions even out in the end; if the umpire said I was out, I was out … but I was still disappointed and I don’t think I truly got over it until I went out for dinner that night with my parents and Nan.