По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

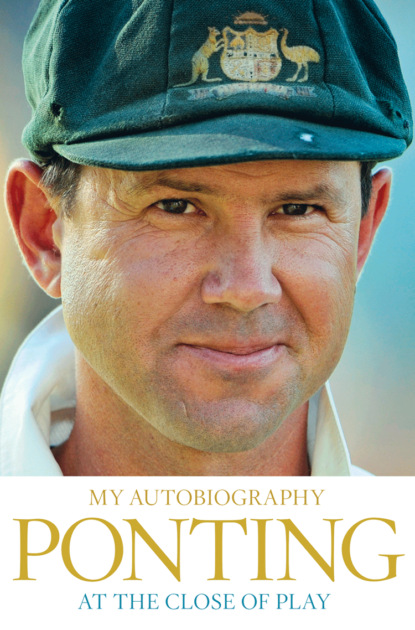

At the Close of Play

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Another four runs would’ve been nice,’ Dad said. ‘But I’m proud of you, we all are.’

Of course, with the Decision Review System (DRS) in place, you’d like to think decisions like that wouldn’t happen today. They’d have gone to the replay and then promptly reversed the decision. But at the time, I was not even aware that Hayat felt he’d made a terrible mistake. When he saw the replay at tea, his umpiring partner on the day, Peter Parker, recalled him being shattered he’d made a mistake. When they first introduced the DRS, I was hesitant, because I always worry about tampering with our game in any way on the basis that it’s pretty good the way it is. But then someone would ask, ‘Don’t you remember your first Test?’ And I’d think, Maybe a review system isn’t such a bad idea.

The last word goes to Nan, who couldn’t hide the fact she was so thrilled with all I’d done and was doing with my cricket. I was so happy she was there to share my first Test with me. As I batted on that third day, and the possibility of me making a debut ton grew closer, the TV cameras found her in the crowd and a reporter went over to see how she was going. Of course, she was asked about that T-shirt — the one she made when I was nine or 10 that said I was going to be a Test cricketer — and she quipped that she was going to print up another one.

‘What’s this one going to say?’ the reporter asked.

‘I told you so!’ Nan replied, and everyone laughed.

I’d missed out on the debut ton, but Nan was right: I was a Test cricketer.

AT THE START of the 1995–96 season, I had been awarded a contract by the Australian Cricket Board. To tell the truth, I can’t remember what it was worth — if I had to guess I’d say around $50,000, with the potential to make quite a bit more — which reflects the reality that at this stage of my life I just didn’t care what they were paying me. Occasionally, I’d hear a senior member of the Australian team muttering about how badly we were being paid, how the ACB was ripping us off, and I’d just nod my head and move on. I just wanted to play. The ‘security’ a contract brought meant nothing to me, because it didn’t guarantee I was going to be involved in the next game. What mattered to me was how well I played, not how my bank account looked.

For me, the best part about getting the Board contract was that it meant the people running cricket thought I deserved it. The combination of their backing, the camaraderie I felt in the Caribbean and the belief I had in my ability meant I felt a genuine sense of belonging when I played top-level cricket, even though I was not yet 21. This was a step up from the confidence the Century Club had in me when they sponsored my trip to Adelaide, that Rod Marsh had in me when he freely told others that he thought I could play, or that companies like Ansett, Kookaburra, Launceston Motors and the Tasmanian TAB were showing in me when they signed me up for cricket scholarships or sponsorship deals.

It was as if I’d moved from standby to actually having a seat on the plane. I felt like I’d never have to work again. And in a sense that’s what happened, because playing cricket has always been a joy for me. I’ve never felt like I had to be there for someone else’s sake, or because I needed the money. I think if I’d never played in a grade any higher than park cricket I would have been one of those blokes who kept playing forever, into my fifties, just because I love the game so much. I was getting well paid for doing something I would have done for nothing. Few people get this lucky and I’ve never forgotten that.

Every year of my cricket life I’ve had to pinch myself.

Being honest shouldn’t be that hard. It’s a value that every person should have. Honest team members create an honest team — and if you don’t have that, then trust and team values break down. Honesty has been a core value of mine for as long as I can remember. It’s been essential to me, right through my whole career — being honest to myself and to my team-mates, to the media and, above all, to the Australian public and cricket fans all over the world. It’s not a trait that you manufacture; it’s a way you live your life.

It’s also the way you should play your cricket. Honesty in the way you prepare, in your training, in your interactions with your team-mates and in your mental approach to a game. Honesty is integral to how you play the game. Always giving 100 per cent, being true to the values of the team and of your country, and of your team-mates. It’s also about being true to the spirit of the game of cricket. Playing to win, playing within the rules and playing with the integrity that is expected of all cricketers. Honesty is for the public eye but also behind closed doors with the way you communicate and interact with others. For me, honesty is not negotiable.

(#ulink_76e8dc04-78f8-59d1-b156-d088b87825ef)

IN MY FIRST THREE TESTS, I saw a ball-tampering controversy in Perth, Muttiah Muralitharan no-balled for throwing by umpire Darrell Hair in Melbourne and David Boon announce his retirement from international cricket in Adelaide. In between, relations between the Australian and Sri Lankan teams became pretty ugly, to the point that the two teams refused to shake hands after we won the World Series Cup in Sydney.

Simmering in the background was the continuing match-fixing controversy, which had become a headline story in Australia back in early 1995 when it was revealed that Mark Waugh, Shane Warne and Tim May had accused Salim Malik of trying to bribe them to play poorly in a Test match and a one-day international on Australia’s tour of Pakistan in 1994.

During the following October, Malik was cleared by Pakistan’s Supreme Court. But the so-called Malik affair didn’t end there. It was to be in and out of the courts for another ten years.

Then on January 31, 1996, two days after Boonie’s farewell Test, a huge bomb blast went off in Colombo, where we were scheduled to play a World Cup match two-and-a-half weeks later. The loss of life was horrifying. Some of the guys received death threats, I was being asked questions about being a possible terrorist target, and not everyone was keen to go to the subcontinent for the Cup. I hadn’t been prepared for any of this and wasn’t sure what to make of it all.

I was supposed to be soaking up every moment of being a Test cricketer, but there was so much going on around the games it was almost overwhelming.

The ball-tampering episode in Perth was a bit of a joke, because the umpires didn’t take the allegedly damaged ball out of the game, so it was a bit hard later on for anyone to determine if the Sri Lankans had done what the umpires reckoned they had. In the Boxing Day Test, Darrell Hair cast his verdict against Murali from the bowler’s end, where I would have thought it was harder to make a clear judgment than if he was standing at square. Mark Waugh reckoned Hair’s no-ball calls were the worst thing ever, because for the rest of the day every time Murali bowled the crowd was yelling, ‘No ball!’, which was very off-putting for the batsmen. Mark was eventually bowled, when he gave himself some room and late cut the ball onto his leg stump. Not his off-stump, his leg stump!

In our dressing room, we initially thought Murali had been no-balled for over-stepping the popping crease, but when the umpire kept going we quickly realised something awful was happening and I couldn’t help thinking that if there was a problem with his action there had to be a better way to fix it than to slaughter him on such a public stage. There had been some talk among us about Murali’s action, with a few guys adamant that his action wasn’t right, but I’d say the overriding view was that it wasn’t for us to worry about. Our job was to work out a way to counter him. I came to see his action as unusual rather than bent, and because his top-spinner often deviated from leg to off, we had to be wary of him in the same way we’d be careful against a leg-spinner with a good wrong’un. Over the years, scoring runs against Murali would become among the biggest and most enjoyable challenges I’d face as a Test batsman.

As things turned out, the only time Sri Lanka beat us in Australia in 1995–96 was in a one-dayer in Melbourne, the irony for me being that this was the game in which I scored my first ODI century. Batting at No. 4 and in at 2–10 in the seventh over, I lasted until the last ball of the innings, when I was run out for 123. There are two things I clearly remember about this knock. One, I hit a six, which was very rare for me in those days. I wasn’t sure I could hit it that far on bigger grounds like the MCG and the SCG, which is a reflection on where I was in my physical development and also on the bats we used then compared to today’s much more powerful pieces of willow. Here, I charged down the wicket and hit one as hard as I could right out of the middle of my bat … and it landed three rows beyond the boundary fence. And two, I didn’t claim the man-of-the-match award. That prize deservedly went to Romesh Kaluwitharana, who set up Sri Lanka’s run-chase with a superb knock of 77 from 75 balls. Ironically, when we talked about the defeat straight after the game we thought his effort was a fluke — it was only his second innings as an opener in ODI cricket and most people in those days still thought it was a top-order batsman’s job to build a platform and help ensure there were wickets in hand for a late-innings assault. In fact, Kaluwitharana’s smashing innings was the start of a revolution that would gain traction during the 1996 World Cup and explode from there in the hands of dynamic top-of-the-order hitters such as Australia’s Adam Gilchrist, India’s Sachin Tendulkar and Virender Sehwag, Sri Lanka’s Sanath Jayasuriya and South Africa’s Herschelle Gibbs.

The best thing about my hundred was that it locked up a World Cup spot for me. I thought I batted really well when I scored 71 in the Boxing Day Test (a game in which I also took my first Test wicket: Asanka Gurusinha, caught by Heals before I’d conceded even a single run as an international bowler and after I thought I had him plumb lbw with a big inswinger), but my batting form in the early World Series Cup games was mediocre and with Steve Waugh due to come back into the team, my place might have been in jeopardy if I’d failed again. Instead, Michael Slater was dropped when Steve returned, Mark Waugh went up to opener and I became the new No. 3. I’d stay at first drop pretty much full-time for the next 15 years.

THREE DAYS BEFORE the Adelaide Test, we met with the ACB to discuss the World Cup tour. A civil war in Sri Lanka had been going on for more than a decade, and while Australian teams had toured there as recently as 1992 and 1994 (and I’d been there with an Academy team in 1993), fighting in the country had escalated in recent times and there was a real fear that terrorists might see the World Cup as a vehicle to push their cause. Further, some Australian players and coach Bob Simpson had received threats suggesting their lives were in danger if they went to Sri Lanka, a frightening state of affairs. However, I was still keen to tour and I went into the meeting dreading the idea that choosing not to tour might be an option. With hindsight, thinking this way was naive, and I have to say that not everyone shared my enthusiasm, but I didn’t want to miss a minute of being an international cricketer.

Mark Taylor initiated discussions by asking what our alternatives were. Did we have to play every game or could we just go to India and Pakistan, where all our World Cup matches bar the Sri Lanka group game were scheduled? Was it one Aussie player out, all out? The ACB bosses said we could pull out of our pre-tournament camp and opening game in Colombo, but if we did that it would put back relations between Australia and Sri Lanka by a decade.

‘Okay then,’ said Tubby. ‘What security measures will be in place?’

First, we were assured that the ACB had been to Pakistan and was happy with the arrangements that had been promised. For Sri Lanka, we would be treated the same way as a visiting head of state. We would leave the airport from a different exit to the general public, after going through a special passport control. There would be no parked cars on the sides of the roads we’d be travelling on and armed guards would look after us 24 hours a day, patrol the ground at practice and ride with us on the team bus. Our luggage and gear would travel on a different bus to us, and no one else would be allowed on our floor of the hotel. The only time we could escape this protection was when we were in our hotel rooms. It all blew me away, such a total contrast to the days when I used to ride my BMX bike from Rocherlea to Invermay Park.

We were grateful for all this, though that feeling was tempered by the news that the ACB had only just received a fax saying that we would be greeted by a suicide bomber when we landed in Colombo. Craig McDermott had received a chilling message that stated he would be ‘fed a diet of hand grenades’, Warnie was advised to look out for a car bomber, and a couple of their players had told us on the field during matches that if we went to Colombo we’d be ‘blown up’. Our security experts advised us that if we received a suspicious-looking parcel it would be best not to open it.

Before the final day’s play of the Test, we had a players’ meeting in which we decided unanimously to go, with the one change that our pre-tournament camp would be in Brisbane. But two days later, a huge bomb blast exploded in the centre of Colombo, just a few blocks from what was going to be our hotel, killing more than 100 people. When I heard about that, I suddenly didn’t want to go to Sri Lanka. I would have gone if we’d been made to, but soon the call was made by the ACB, in consultation with Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs, to abort the Sri Lankan leg of our tour. We were criticised by some people on the subcontinent and a few dopey columnists in England, and the World Cup organising committee ruled it a ‘forfeit’ and gave the two points to Sri Lanka, which seemed a bit ridiculous but didn’t worry us at all. Thinking about it now, I’m sure not going was 100 per cent the right decision.

SO WE WOULD BE going to the World Cup, but one man who wouldn’t be travelling with us was David Boon, who called time on his international career after the Tests against Sri Lanka. It is one of my regrets in cricket that even though we played three times together at the highest level I never managed to bat with Boonie in a Test match. However, that doesn’t diminish the huge influence he had on me as a cricketer, how much he helped me from the time he was making it possible for all young cricketers in Northern Tasmania to realistically dream of greatness to the days we were together in the same Aussie dressing room.

Of all the things he taught me about big-time cricket, the thing that stands out most for me is patience. I was lucky in that from when I first came into the Tasmanian team, I could observe him closely at training and in games and study the manner in which he made the bowlers come to him, how he would wait until the ball was in his area, and then he’d score his runs. ‘You have to know your game,’ he would say. ‘And try to stay out in the middle for as long as you can.’

I thought I knew what he meant when he advised me to ‘know my game’, but in fact I didn’t really get it for a few more years. And that last line might sound obvious, but in my early days in the Tassie team I often threw away a potential big score by trying to blaze away. A rapid-fire fifty might excite the fans, but Boonie knew it was big hundreds that win games and impress the selectors. After I scored my first ODI century, I really felt a part of the side, much more than I did after making 96 in my first Test. In cricket, the difference between two and three figures can be huge, even if it is a matter of two, three — or four — runs.

Unfortunately, my promotion to the Australian side coincided with Boonie’s fight to prolong his Test career. From afar, I’d seen the media pursue out-of-form stars in the past, great players like Allan Border, Merv Hughes, Dean Jones and Geoff Marsh. But that was when I was a spectator; now I got a whole new perspective on the situation. I was at a stage of my career where everything that was written about me was positive, so I was always keen to head to the sports pages. Boonie, about to turn 35 and — as far as some reporters were concerned — well past his use-by date, probably hadn’t read a paper in weeks, but he couldn’t avoid the whispers, the well-meaning advice to ‘ignore what they’re writing about you’, the negative tone of the journalists’ questions. Watching him in the nets, I wondered if he was working too hard, but there was no way a young pup like me was going to say anything. I saw how stoic he was in the dressing room at the WACA after he was fired by Khizar Hayat (I think I’d have flipped in the same situation) and I admired how he fought so hard in Melbourne to score 93 not out on the day Murali was no-balled by Darrell Hair. He went on to his final Test century the following day.

I also was taken by the way he handled his omission from the one-day squad, a decision announced straight after the Perth Test. The sacking of a long-time player always cuts at the psyche of a team, but there was no way Boonie was going to sulk or make it awkward for his mates; instead, as usual, he was one of the first guys down to the hotel bar to toast our Test victory before we headed back to Launceston — me to play golf with my brother, Drew, at Mowbray; Boonie to visit his wife Pip in hospital, where she was recovering from a minor operation. Of all the things on his mind, that was easily the one he was most concerned about.

I’ll never forget how good he was to me on that flight, despite all the turmoil that must have been spinning through his head. He told me how proud he was seeing a ‘fellow Swampie’ making runs in Test cricket, and how determined he was for the two of us to go to England together on the 1997 Ashes tour. It wasn’t to be. I think Boonie found it hard to adjust to being in the Test side but out of the one-day team, and when it became clear he wasn’t going to make the World Cup squad he pulled the pin. He told us at a team meeting just before the Adelaide Test, reading from notes he’d prepared so he got the words right, emphasising how much playing for Australia meant to him and how he had treasured the camaraderie he shared with his team-mates. For 30 seconds straight afterwards there was silence, before Tubby, Simmo and a few of the boys told Boonie how grateful they were to have shared the ride with him.

I didn’t say anything, not then anyway. It was a bit different for me, because Boonie was not so much my team-mate as my hero. One thing he kept saying was that he was very comfortable with his decision to retire, that it was the right time. Well, it might have been the correct call for him, but I’d had visions of playing a lot of Test cricket with David Boon. I wish I could have batted with him in a Test match. One part of my cricket dream was over almost as quickly as it had begun.

(#ulink_733a026e-4c7d-5326-b302-84818cdba20b)

I WAS SEATED in an aisle seat for the first leg of our flight, from Sydney to Bangkok, next to Steve Waugh. Michael Slater, who’d been recalled to the squad, was sitting directly across from me, and he noticed me studying the flash Thai Airways International showbag.

‘It’s just toiletries, mate,’ he said helpfully. ‘Try the breath freshener.’

I unzipped the bag, went through the soap, toothpaste, breath freshener … no, that’s the shaving cream … deodorant. Finally, I found the breath freshener, but initially I was worried it might be an elaborate trap. What was Slats up to? I took the cap off the small bottle, and gave the button a gentle prod, so that just a smidgen of spray came out.

Hey, that’s not too bad, I thought to myself, as I nodded in Slats’s direction. Thai’s business class was so impressive I was beginning to think they’d be serving Tasmanian beer on the flight. Then I looked to my right and saw that rather than checking out what freebies might be on offer, Steve Waugh was intently studying the new laptop one of his sponsors had given him to help him type his next best-selling tour diary. He hadn’t heard what Slats and I had been talking about.

‘Hey Tugga, have you tried the breath freshener?’ I asked, as I passed a bottle over to him.

‘Thanks, mate,’ he replied, as he put the nozzle to his mouth and pushed hard.

But it wasn’t the breath freshener; it was the shaving cream. I’d done him beautifully. He spat the foam out all over his new laptop, muttered something about me being a ‘little prick’, and then had to call a flight attendant over to clean up the mess. Once that was done, he looked over at me and said, as seriously as he could, ‘Don’t worry, young fella. I’ve got a memory like an elephant.’

He has, too. But while I’m sure Steve would have tried to square the ledger at some point over the following six weeks — and with our first game cancelled he had plenty of time before our opening match — I don’t think he ever did.

AUSTRALIA’S RECORD IN WORLD CUPS prior to 1996 was hardly flash: winners in 1987; finalists in the inaugural Cup in 1975; but couldn’t get out of the first round in 1979, 1983 and 1992. Still, we thought we were a real chance this time, even if we were giving the other teams in our group (bar the West Indies, who also refused to go to Sri Lanka) a game start.

There was a sense of relief and anticipation among us when we finally set off for India, as if we were bidding farewell to the stresses and turmoil of the previous few weeks. In fact, once we landed, we’d be subject to a fair degree of hostility from the locals, who thought we’d overplayed our hand by choosing not to tour to Sri Lanka, but on the plane, at least, we felt far away from that.

THERE WERE ACTUALLY 13 DAYS between our arrival in Calcutta (now Kolkata) and our first game, against Kenya in Visakhapatnam. Those in the squad like Steve and Glenn McGrath, who like to explore, did venture out on occasions, but the high security that accompanied our every move made that even less inviting for blokes like me who aren’t into that sort of thing. As it was I lost a couple of days to a stomach bug and wasn’t going too far from the bathroom anyway, but when I was healthy I was jumping out of my skin at training, and this caused a bit of grief at one session where Errol Alcott had us working in pairs, one guy wearing boxing gloves and throwing punches while the other held up a circular pad to absorb the jabs. All was going well until I aimed a straight right but missed the pad and instead struck Paul Reiffel bang on the bridge of his nose. Fortunately, Pistol was stunned rather than hurt. He quickly told me I was a bloody idiot and then we got on with it.

The fact we were treated as ‘outcasts’ by critics in India helped galvanise the group, to the point that we could belt each other and still be good mates, and our spirits remained pretty high despite the days without on-field action. Interestingly, while some officials and a number of commentators seemed dirty on us, the local fans were mostly positive, and I was astonished by just how many of them squeezed into the ground floor at our hotels — not to harass us, just to wish us all the best and, hopefully, to nab a prized autograph or photograph. Over the years of playing in India this is something I have noticed. The media can be tearing you limb from limb, but the fans are among the most generous in the world and sometimes it pays to remember that.

We were one down before we even started courtesy of missing the first game, but made up for it in matches against Kenya, India and Zimbabwe. Mark Waugh won man of the match in the first two games and Warnie was outstanding in the third.

It was when we headed to Jaipur to take on the West Indies that I started to get some traction and played my best innings of the tournament. Remembering back to our early team meetings in the Caribbean a year before, where Steve Waugh talked at length about not being intimidated by Ambrose, Walsh and company, I went out to bat in my yellow Australian cap. It may have been a reckless show of defiance, but one that had me feeling very good about myself after I survived my first few overs. Mind you, this was after I ducked under the first three balls I faced — all bouncers.