По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

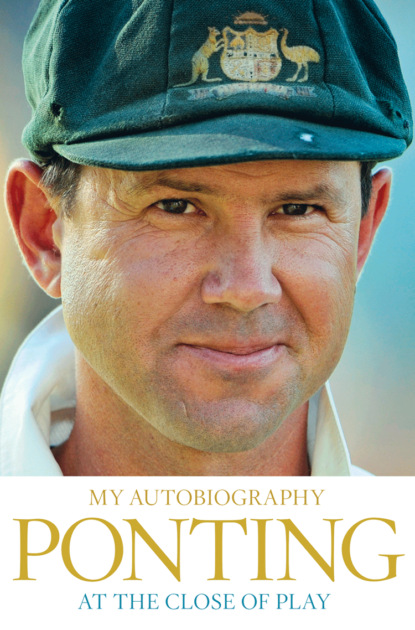

At the Close of Play

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Am I ever going to play Test cricket again?

In the end, after only a couple of days, I said to myself, ‘I’m going to get myself back in the team that quick it’s not funny. I’m going to go back to state cricket and get a hundred every time I bat. I’ll train so hard they’ll have to pick me again.’

IF YOU LOOK AT MY SCORES in the Shield for the rest of the 1996–97 season, you’d think it took me a while to rediscover my form. But I actually felt good from my very first innings in January, when we played Victoria at the MCG. I went out with the intention of batting all day and reasonably quickly I felt the ball hitting the middle of my bat. But when I was on 26 Tony Dodemaide, the veteran fast-medium bowler, suddenly got one to seam back sharply and I managed to get a faint nick through to the keeper. As I walked off after getting a ball like that I felt like I was the unluckiest cricketer on the planet, but in our second innings I made 94 not out, my knock ending only when Boonie declared in pursuit of an outright victory. Then came a frustrating fortnight, where I was hitting the ball beautifully in the nets but could only make 8 and 6 against WA at Bellerive and then 39 against SA in Adelaide. I thought the world was against me.

Trevor Hohns had told me to score heavily and if I wasn’t doing that, I knew I was no chance of making the upcoming Ashes tour. After that Shield game in Adelaide, I thought, This is not working. By ‘this’, I meant working my butt off. We finished early on day four and as soon as I could I booked a short holiday to the Gold Coast. For the next three or four days I didn’t think about cricket and I left it as late as possible to get back to Hobart for our next match. When I did get home, I only had time for a couple of training sessions and then I immediately scored a hundred in each innings against South Australia at Bellerive.

I actually learned a lot about myself and what was best for me during this time. Hitting a million balls a day and training as hard as possible was not always the solution, especially if I felt I had to do it. Sure, I’d spent a lot of time in the nets before this but I’d never forced myself to go, to do even more, as if that was the only answer. When things weren’t working, I was better off trying to freshen up mentally, and the best way to do that was forget about the pressures of the game. I learned there is a difference between letting it happen and forcing it, in trusting my skills rather than searching for something more.

The other thing that was crucial for me at this time was the support I received from Tasmanian coach Greg Shipperd. When I was working hard at practice, hitting ball after ball, he was always in my corner. He also offered what proved to be a critical piece of advice. My confidence had taken a hit, and Shippy was convinced I’d got into the habit of trying to hit my way out of trouble when things grew difficult. Of course, every batsman has rough spots during an innings of any length, especially if you bat near the top of the order and the pitch is offering some assistance to the bowler, but my brain was getting cluttered when this happened to me.

In the first innings against SA, I scored 126 out of 248. Then Jamie Siddons, the SA captain, made a very positive declaration on the final day, which gave me the opportunity to produce an even better effort than my first dig. We had to win to keep our Shield chances alive and I was in at 2–52 as we chased 349 to win. Four hours later, we’d achieved a terrific victory and I had played an important part, finishing 145 not out. Selectors love match-winning hundreds, but even more important than that I’d been intimately involved in a special team victory, which reminded me of just what a great game cricket can be. In all the stress of losing and then trying to revive my international career, I’d forgotten a little of that.

I made another big hundred in our next Shield game, against Queensland and finished the season with scores of 64 and 22 against NSW at the SCG. It was time to wait for the Ashes touring party to be named. I went through all the options available and realised that even with my big finish to the season, I was hardly a sure pick. The Test team had won the home series against the West Indies 3–2 before heading to South Africa, where it was in the process of claiming a hard-fought three-game series 2–1. However, question marks were hovering over the batting order, with Mark Taylor completely out of form and none of the excellent batsmen from my generation on the tour — Matthew Elliott, Michael Bevan, Greg Blewett, Matthew Hayden and Justin Langer — having cemented their spots. But none of them had cruelled their chances completely either. The media in Sydney was campaigning for Michael Slater to be recalled, while it was certain that Adam Gilchrist, who had enjoyed a fantastic season with bat and wicketkeeping gloves for WA before flying to South Africa to bolster the ODI line-up, would be Ian Healy’s back-up. What if the selectors looked upon Gilly as a batsman too, and decided to take an extra bowler? What if they decided to look for experience, and opt for either of the Shield’s leading run-scorers for the season — Tasmania’s Jamie Cox or Darren Lehmann of South Australia — or Stuart Law, who was still playing one-day internationals but who hadn’t appeared in a Test match again since we debuted in the same game.

In the end, I think I was very lucky. Looking at the make-up of the squad now, it was top heavy with batting talent. Bevo was picked as the second spinner and Gilly as the second keeper, but the selectors still chose eight more specialist batsmen: Taylor, the two Waughs, Elliott, Blewett, Slater, Langer … and Ponting. I’ve always wondered, but I’ve never been game to ask, if that request Trevor Hohns had made of me — to go back to the Shield and score a ‘hell of a lot of runs’ — was what got me over the line. I’d done what he’d asked me to do, so maybe he and his fellow selectors felt obliged to honour their side of the bargain by giving me another go. It would have been far from illogical to pick one less batsman and one more bowler; as things turned out, a couple of the batsmen hardly had a dig on tour, while we had to call up some extra bowlers after the first choices suffered major injuries.

What I know beyond question is that my career might have turned out very differently if I hadn’t been chosen for this Ashes tour. Matty Hayden missed the trip and didn’t get another opportunity for two-and-a-half years. Great players like Damien Martyn and Darren Lehmann had been picked for Australia as prodigiously talented young players in the early 1990s, but after being discarded it would be ages before they would be granted another go at the top level. In contrast, I was very fortunate. My second chance came quickly. I was determined not to waste it.

I’m a watcher, a listener, a learner. I like to sit back in the corner and take everything in; learn as much as possible from as many people as I can. I’ve never really had any defined role models in my life but there have been plenty of people who I’ve watched very closely to help me be a better person. Bottom line for me has been that it’s up to me to be the best possible person that I can be. I had an understanding of where I wanted to be as a cricketer and as a person. I’ve always just been me. Anytime I messed up along the way, I’ve given myself a kick up the backside and then got on with things, making sure that each day I got up, looked in the mirror and asked myself how I could be a better person today. In many ways, I’ve been my own harshest critic but it’s helped me respond at times when I’ve most needed to. It’s helped me be true to myself and those around me and probably also helped me be a better role model for those looking to me as an example for how they might live their lives. That’s a big responsibility in many ways but one I have always been comfortable with.

(#ulink_f9791692-0589-5623-84ae-58b39e26b52c)

IT WAS A WEIRD experience, reacquainting myself with the other members of the Ashes squad for our flight to London via Hong Kong. I felt like I’d been out of the team for ages, rather than just five months, and quickly I discovered that things had changed a little in the time I’d been away.

Mark Taylor had been struggling for runs, but had stayed in the Test team and ODI squad despite his lack of form, a policy that impacted on the positions of a few other players. Most people were talking about the selection of Michael Bevan, a left-arm wrist spinner as well as a fine batsman, who was picked as the fourth bowler for the Tests in South Africa ahead of Paul Reiffel, seemingly to stiffen the batting order, even though the pitches over there suited the quicks.

When Pistol then missed selection for the Ashes tour some critics reckoned his career had been set back for the sake of the captain. At the same time, Steve Waugh replaced Ian Healy as vice-captain, which seemed to have shaken our champion wicketkeeper. You could see, even on the flight to England, that he wasn’t his usual chirpy self. That change, we all understood, had been made so that if Tubby was dropped from the Test XI in England, Tugga would be his replacement, but Heals couldn’t understand why he couldn’t remain the deputy no matter who was in charge. I couldn’t either.

In the years since, I have read stories of how the team was split, but I can’t recall any major blow-ups, just that mood shift, that sense that things weren’t quite right. Looking back over the statistics, it is a little surprising that Tubby survived his run of outs — at the start of this Ashes tour, he hadn’t scored a Test fifty since early December 1995 and since I’d been dropped he’d scored 111 runs in 10 Test innings — but I was not the sort of person to get involved in conjecture about another player’s place in the team, especially when he was the captain and I was a young bloke lucky to even be on the tour. I’ve always hated seeing behaviour or hearing talk that might divide my team. This time, my attention was devoted to forcing my way back into the side.

However, there were moments that showed just how much our captain was struggling with the bat, and not all of these were in the early weeks of the tour. The day before the third Test at Old Trafford, I was standing near the entrance to the nets, waiting for my turn to bat, which gave me a close-up view of him struggling to lay bat on ball. It looked like Michael Kasprowicz and Paul Reiffel (who’d been called up as a replacement after Andy Bichel was hurt) were bowling at 100 miles an hour, and when Tubby walked out of the net, he said to me, ‘If you can lay bat on those blokes in there you can have my spot in the Test.’ In reality, batting in that net wasn’t all that difficult. I also recall him saying to Matthew Elliott one day, ‘Next time, I’ll wear your helmet out. If I look like you out there maybe I’ll get a few half volleys and a few cut shots like you’re getting.’ Tubby had convinced himself his batting was just one long hard-luck story. Everything was going against him.

In fact, if my memory is right, he got a bit lucky. We played Derbyshire just before the first Test and when Tubby batted in our second innings, his former Aussie team-mate Dean Jones dropped him a sitter at first slip, and he went on to make 63. Four days later, the boys were bowled out for 118 after being 8–54 on the first day of the opening Test at Edgbaston. England replied with 478 before Tubby famously saved his career with a sterling 129. Even though we lost the game by nine wickets, the turnaround in our fortunes was massive. Finally, we could stop responding to the rumours that the skipper was about to get dropped and start concentrating on retaining the Ashes.

To this point, my on-field contribution had been minimal. I batted with little success in our first three matches — an exhibition game in Hong Kong and one-dayers at Arundel and Northampton — and then didn’t play for a month, missing a limited-overs game against Worcestershire, three ODIs, three-day games at Bristol and Derby, and the opening Test. First, I was told they had to give the guys in the one-day team the playing time; then it was the guys in the Test team. At practice, I often had to wait for ages to get a hit and it reached the stage where I was spending more time bowling off-breaks as a net bowler than I was playing off-drives. When I did eventually get a chance, in a three-day game against Nottinghamshire, the first day was washed out completely, and when we did get on the field I batted at three and was lbw for just 19. Fortunately, they chose me again for the next fixture, at Leicester, and I managed to score 64 in our first innings, when the only other contributors to get past 20 were Heals (34) and extras (48). When Michael Bevan failed with the bat in the third Test, which we won to level the series, I was suddenly in the running for the Test team.

Things really did change that quickly.

Before the first Test, the selectors were auditioning Greg Blewett and Justin Langer for the No. 3 spot, with Bevo certain to bat at six because his spinners added depth to our bowling attack. Greg made a hundred against Derbyshire, while Lang failed in both innings, and from there my little mate from Perth gradually faded from contention while Blewey hit a century in the first Test and locked up his place for the series. There were three weeks between the third and fourth Tests, and after a sojourn to Scotland we found ourselves at Sophia Gardens in Cardiff, for our tour game against Glamorgan. Tubby won the toss and batted first, and I went out and scored 126 not out, while my main rival for Bevo’s spot, Michael Slater, was out for exactly 100 runs less.

When we batted again, Slats opened the batting and was out for 7, and I was kept back to give others a knock, as if I was now one of the Test regulars. There was one more game before the fourth Test, against Middlesex at Lord’s, and I was picked again, to bat at six after the guys who had batted one to five in the first three Tests, and the strong impression I was given was that this was being seen as a rehearsal for the big game a week later. If it was, I didn’t do myself any favours — out for just 5 — but it didn’t matter. When they announced the team for Headingley I was in, and I felt the same emotions as when I’d learned I was going to make my Test debut, only this time the stakes were higher. It wasn’t just that this was the Ashes, cricket’s oldest trophy, the contest all budding Aussie cricketers dream about; this time, I really thought my career was on the line, that if I stuffed up this chance I might not get another.

It’s funny how cricket takes you down a rung. By comparison I’d been reasonably confident when I made my Test debut, but from the moment you’re dropped the game becomes another proposition and the older you get the harder it becomes to deal with those mental pressures. For that reason I have always been wary of axing young players or any player when it comes to that. If you’re going to do it you have to understand the profound effect it will have on the person and be aware that it can genuinely set people back. Greg Chappell always said it was better to give somebody one Test too many rather than one too few and I agree.

THE OTHER BLOKE who might have been a chance to bat at six for Australia in that fourth Test was Adam Gilchrist but, cruelly for him, he wasn’t available. Instead, he was flying home, having hurt himself during a training session in the lead-up to the third Test. We were playing ‘fielding soccer’, which as its name implies is a game where you pass a cricket ball to a team-mate by throwing it below knee-height and attempt to score. I was standing slightly in front of Gilly when someone threw the ball to his left, and I dived in front of him to try to cut the ball off, he put his left leg in front of my dive, I clipped the side of his knee, and down he went. Within 10 minutes, you could prod your fingers into his leg and it felt and looked like Play-Doh, all the way from his ankle to his knee. The eventual diagnosis was a torn ligament and poor Gilly was on that plane home. We still have a bit of a laugh about my dive being ‘deliberate’ — that was the only way I was going to get a game on the tour. It would have been a bold call, picking our second keeper as a specialist batsman in the Test team, but he had played in two of the three ODIs as a batsman, so it wasn’t completely out of the question.

I was very sorry to see Gilly depart. In the early days of the tour, when morale wasn’t as bubbly as it could have been it was almost inevitable that we young blokes would seek refuge in each other’s company, and bonds that were first established at the Academy or on youth tours were forged tighter. Gilly and I have a lot in common, from a love of harmless practical jokes to enjoying working hard at practice. But the team-mate I grew especially close to on this tour was Blewey, who shares my passion for golf, and we had time to experience a number of famous courses, including the Belfry, St Andrews, Sunningdale and Royal Portrush.

The day at St Andrews felt almost like a pilgrimage to me; I’m not sure I felt a similar sense of golfing anticipation until the day I visited Augusta for the US Masters in 2010. However, purely from a quality-of-layout perspective, Royal Portrush on Northern Ireland’s north coast was superior, as good a links course as I will ever see. In fact, I enjoyed every minute of our three-day trip to Ulster that came near the end of our tour: the local Guinness was superb and I scored an unbeaten hundred and took 3–14 in our one-day game against Ireland. Another enjoyable excursion was to the famous Brands Hatch motor racing circuit where I met for the first time Australia’s future Formula One ace Mark Webber. Mark was a cricket tragic and we would catch up quite often in the following years. For a guy who drives million-dollar racing cars at a million miles an hour he is as laid-back and unassuming as anyone you would ever meet.

Keeping up with the AFL and the greyhounds back home was one of the challenges of travelling, and more than once I’d call home and ask someone to put the radio to the phone so I could listen to an important race. Junior was much the same. In the match against Nottinghamshire, I was dismissed in the first over of the day after he had said to me, ‘I’m next in, so don’t you dare get out early today. I’ve got to listen to a race.’ He was in a toilet cubicle at the back of the change room and the horses were lining up behind the mobile start when I let him down. He had to hang up with his horse in contention a couple of hundred metres from the winning post.

MY RETURN TO THE Australian team for the fourth Test was confirmed on the same day we met the Queen at Buckingham Palace, a visit I remember most for Michael Kasprowicz’s extended conversation with Her Majesty about the virtues of the Gladiators television show.

Two days later the critical Test started — the series was level at one-all — and we were in the field on a day that was interrupted by rain and England finished at 3–106. The next morning, Jason ‘Dizzy’ Gillespie ran right through them, bowling outswingers like the wind and taking 7–37 as we knocked them over for just 172.

Our reply started badly, with Mark Taylor caught behind off Darren Gough for a duck and Greg Blewett going the same way for 1, leaving us at 2–16. At this point, I went to find my box and thigh pad. Matthew Elliott and Mark Waugh steadied the ship a little, until Junior was caught and bowled by Dean Headley, which was when I started putting the pads on. Steve Waugh, fresh off scoring a century in each innings in the third Test, strode out to put things right, but I had only just taken up a position in our viewing deck when ‘Herb’ Elliott edged a sitter to Graham Thorpe at first slip. The chance went so slowly I was actually up off my seat, ready to get out there, but then I saw the ball on the turf. Not that it seemed to matter, though, because next over Tugga was caught at short leg. My first innings in an Ashes Test was about to begin and at 4–50 we were not in a good position.

I’d been nervous before the game, but not so much now. It’s not like I was relaxed, as if it was just another innings, but when I walked out there my main thoughts were about getting us back into the game, rather than what might happen if I failed, or what the wicket might be doing, or how everyone here and back home was watching me. Maybe the fact the experienced guys had been dismissed cheaply took a little personal pressure off me. Mostly, I think the situation of the game was good for me, in that I was in a position to do something really big for the team. The great golfer Peter Thomson once wrote how ‘hope builds, fear destroys’ and my mindset as I began this innings reflected that. I wasn’t thinking about failing, only about fighting back.

I was also lucky in that I’m not sure the Poms were too thorough when they did their homework on me. The ball was seaming about but they seemed keen to test me out with some short stuff and I relished the chance to show them I could hook and pull. To get off the mark, I pulled a bumper from Headley which rocketed to the boundary and the confidence that one shot gave me was liberating. None of the English quicks were very tall, so whereas Pigeon and Dizzy had got the ball to lift a little dangerously from this wicket, their short ones just came onto the bat sweetly. And then my on-drive started working and I knew it was going to be a good day. Herb and I were also helped, I’m sure, by the fact the pitch settled down as the day went on. I reached my fifty just after we passed their first-innings score. The sun had come out and by late in the afternoon the conditions for batting were excellent, the Englishmen dropped their heads, and we reached stumps still together with a lead of 86 (coincidentally, I was 86 not out). Not for the last time, I discovered how much batting conditions at Headingley can change when the sun comes out.

The only time I felt the nerves getting to me occurred on that third morning, when I was in the 90s, but luckily a couple of loose deliveries helped me out. I’d slept better than I’d expected overnight — no dreams about crazy run outs — but then right away I played a streaky shot down to third man to go from 87 to 91, and for a moment I had to fight the memories of Perth and the frustration of falling short there. There was some cloud cover and Headley’s outswinger was working, but then he bowled a nice half volley, which I drove to the extra-cover boundary, and then a short one which I hit off the back foot to exactly the same advertising hoarding. The second new ball was due in a few overs, so they had their off-spinner Robert Croft bowling at the other end, and when I got down there I was very keen to take him on. On 99 I actually ran down the wicket and tried to slog one through or over the legside, but all I did was inside-edge it onto my leg and it finished down near the stumps as I rushed back into my crease. Just calm down! Now my plan was to nudge one into a gap on the legside any way I could. I’m not really sure it would have mattered where his next delivery pitched, that’s where it was going, but Croft helped me out by flighting one into my pads. I called Herb through and as I dashed down the wicket I nearly pulled my right arm (the one holding my bat) out of its socket as I punched the air in delight.

I can think back on a range of emotions. Later, even a few seconds afterwards and certainly that night when I thought back on what I’d achieved, there was a huge sense of relief that I’d reached the milestone and answered those who’d doubted me — you can see it on the video, how I let out a deep breath and then had my tongue out, a bit like a runner at the end of a tough mile. But the first moment after I reached three figures was sheer joy. I was also very, very proud of myself, that I’d made the ton and that I’d fought back successfully from the hurt and embarrassment of being dropped the previous December. From the time I was seven or eight years old I had been dreaming about this moment. All the training, the time at Mowbray and the Academy, the junior and senior and Shield cricket, had all been about making centuries for Australia and scoring runs in pressure situations in Test matches. No, not just Test matches, in Ashes Test matches. There is a lot of work that goes into your first Test hundred and I revelled in the sense of satisfaction. And it was so rewarding to see champions like Warnie, Heals and Junior up on the players’ balcony, applauding. Those guys, all the guys, were genuinely happy for me and that made me feel very important.

We carried on and on until we’d added 268, one of the best partnerships I was ever involved in (apparently it was the third highest fifth-wicket stand for Australia in Ashes Tests at that time). I was dismissed for 127, Herb went on to become the third man and first Aussie to be out for 199 in a Test. That was the only downer of the whole experience — he batted beautifully, there was no question he deserved a double ton.

We went on to complete an emphatic victory, winning by an innings and 61 runs, and two weeks later we retained the Ashes when we decisively won the fifth Test at Nottingham. Not even a loss at the Oval, when Phil Tufnell spun England to victory on a substandard wicket to make the final series score 3–2, could take the gloss off what had become a brilliant experience. Today, I think back fondly on both the hundred and the way I handled the stress and disappointment of being out of the team as if the two go together.

I also like to reflect on how we retained the Ashes in England, which despite what a few outsiders thought at the time is no easy task. The speculation that had followed the team for the first month of the tour was long forgotten, the credit for which must primarily go to Tubby, for his persistence, the mental strength he showed when under duress, and for his great tactical ability, which during the middle of the series shone brightly time after time. The way the team regrouped under his leadership was remarkable, and I was proud to have played a small part in that.

(#ulink_a2840238-8153-5e01-9011-9eb16de92a42)

Loyalty and trust are two of the most important traits that I look for in a person. They are certainly core values in my life and are becoming even more important as I grow older and wiser. A successful team will have a high level of trust and loyalty built into its values and performance. The individuals within that team will have a strong team ethic as a natural behaviour, having taken themselves out of their individual approach and behaviour. These individuals are conscious of the needs of their team-mates, providing a level of co-operation and trust that helps the whole team perform at its best.

I probably trusted people too much. While I was aware that not everyone shared my views on the importance of putting the team before oneself, I still gave all of my team-mates the opportunity to develop these characteristics to strengthen the team. If players broke mine or the team’s trust, I would let them know straight away. I would make it very clear that they had let the group down and they needed to go away and rebuild the team’s trust, my trust, and their own trust. Most of the time, this happened, and I’d sit back and watch the players do their best to make up for their indiscretions. If they fell back again, for a second or third time, I was a lot harder on them but overall was probably very forgiving.

My own loyalty to the team and my players was really important to me. I was absolutely willing to back all the players I played with. I wanted stability around the group and would do my best to fight change. I wanted new players who came into the group to feel this loyalty and trust. I treated everyone as an equal and went out of my way to give new players this feeling, in the aim they didn’t feel less valued than those players who had been with the group for a long time.

(#ulink_7e505cfb-0a88-549d-a098-68f8dcabf00d)

AS A YOUNG PLAYER, I was often surprised by the self-importance of some cricket officials. Not all of them — there were many smart, hard-working administrators who went way beyond the call of duty for the sake of the game and its players, but there were others who I came to view as nothing more than hangers-on. These people seemed to be there for what they could get out of it, the free lunches and the plum seats in the stands. They were the bosses and we Test players merely the workers who if they had their way would come and go from the tradesmen’s entrance. Their attitude whenever a cricketer or group of cricketers sought improvements to wages or playing conditions appeared to be simple: ‘If you don’t like what you’re getting, there are thousands of others out there who’d gladly play for nothing.’

Some, astonishingly, were past top-level players, who’d had this attitude ingrained into them and now fought to preserve the status quo for as long as they could. Here’s just one example. In 1997, our manager Alan Crompton agreed to a request from Mark Taylor for the players’ wives and partners and children to travel with the team for the month from the start of the second Test match. I was only 22, but even I could see the benefits of this move, not least for how the older guys treasured the chance to share the experience with their kids. Today, few would argue with the concept of families being on tour, but things were different back then. I learned recently that a number of Board directors, one of whom was a former Test player, were vehemently against the innovation, their argument being, I guess, that ‘it didn’t happen in my day’.

By the mid 1990s, the senior members of the Australian side were sick of this. I might have been new to international cricket, but it seemed to me that in arguing for a better deal my experienced and battle-hardened team-mates had a pretty fair case. And so it was that I was a first-hand witness as men like Tim May, Shane Warne, Steve Waugh and Ian Healy fought long and hard to win Australia’s front-line cricketers a much better deal than we might have otherwise enjoyed. Their battle also led to an improved relationship between the players and the Australian Cricket Board, and it increased the professionalism of the Board, too. In the years that followed, the way our administration thought and operated finally moved with the times, and some of the Board’s revenue streams— including media rights, sponsorship and merchandise — increased dramatically. This would not have happened, at least not as quickly, if my team-mates, some of the great players of the 1990s, had declined to make a stand or if some of the officials had got their way.

Having gone on to captain the Australian team, and to have enjoyed so much of the fruits of their labours, it would be nice to describe here how I played a major role in the birth of the Australian Cricketers’ Association (ACA), but the truth is I was on the periphery. I certainly didn’t feel underpaid — I was probably the best-paid 21-year-old in Tasmania — but that didn’t stop me being 100 per cent behind whatever direction Maysie, Tugga, Warnie and Heals wanted us to go in. I was young and new to international cricket, but I believed strongly in the concept of ‘team’ and I had complete faith in the leadership group. ‘You can count me in,’ I quickly said after the ACA concept was explained to me.

For me, the story began at the start of my first major trip — the West Indies in 1995 — when everyone in the team was invited to a pre-tour meeting in Sydney. Thinking back, it was a pathetically unprofessional scene: the players were lying on a bed or on the floor while then Board CEO Graham Halbish told us how things would be. Some of the players were clearly frustrated with Halbish’s responses to their questions on subjects like player payments, personal sponsorships, TV rights and insurance, and there were some terse exchanges.

This was also the meeting when we were officially told that Salim Malik had been accused of attempting to bribe Tim May, Shane Warne and Mark Waugh, a story that had just been broken in the newspapers, and that Mark and Shane had been punished by the Board for ‘supplying information’ to an Indian bookmaker. Apparently, we were firmly told these matters were not to be discussed with anyone outside the room, but I can’t recall that direction being given. I guess I’d tuned out by then.

I was new to debates about player payments. Whatever they wanted was fine by me; whatever they paid me was more than I could have dreamed of when I was pushing lawn mowers for Ian Young at Scotch Oakburn College, and more than any of my mates from school were earning. More than once on that Windies tour I heard team-mates comparing how much we were paid to the huge sums being earned by stars from other sports, how poorly Shield cricketers were being treated and the restrictive nature of the Board’s player contracts, but I hardly stopped to listen.

The Australian Cricketers’ Association was formed after the tour, with Tim May, whose Test career had come to an end, getting the gig as our union boss. Over the next two years Maysie tried to get the idea of payments for Test and Shield players to be tied to the Board’s revenue, but the Board wouldn’t have a bar of that. It wouldn’t even discuss the concept.