По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

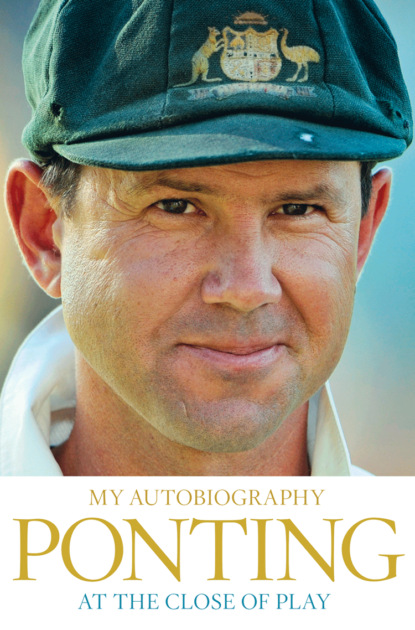

At the Close of Play

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

My best moment of the innings came when I charged one of their best quicks, Ian Bishop, and put him into the crowd beyond deep extra cover — this might have been the best shot of my life — and I managed to get to my hundred before our 50 overs were up, but then their captain Richie Richardson and star batsman Brian Lara came together in a match-winning partnership.

Late in the day, we were still an outside chance of winning if only we could dismiss the Windies’ skipper. Mark Waugh did him slightly in the air as he went for a slog-sweep over mid-wicket. I was riding the boundary and I back-pedalled and back-pedalled … and held the catch Australian football-style above my head … then stumbled on the rope and fell back into a Coca-Cola advertising hoarding perched just beyond the playing field. Six! Soon after, the game was over, Richardson was undefeated, 93 not out, with my innings from earlier in the day all but forgotten. This meant I’d scored two ODI centuries and we’d lost both times.

In between this loss and our quarter-final against New Zealand in Madras, we flew back to Delhi, attended a function at the Australian Embassy, and then early the next morning set off by bus for Agra to have our official team photograph taken with the Taj Mahal as the backdrop. The photo was taken with us in our canary-yellow uniforms, and when someone produced a footy I was one of a number of Aussie cricketers seen trying to take ‘speckies’ among the tourists. Four days later the Kiwis set us an imposing 287, but Junior was in imperious form as he made his third hundred of the tournament and we won by six wickets with 13 balls to spare, to set up a rematch with the West Indies, who’d stunned the favoured South Africans in their quarter-final in Karachi.

OF THE MANY ONE-DAY victories I enjoyed over the years, this semi-final against the Windies in Mohali is often forgotten, but it is right up among the best I was involved in. For much of the day it looked like we were going to lose, but there was real spirit about our team and we just refused to be knocked out. I was dismissed for a 15-ball duck, one of the four wickets to fall in the first 10 overs of the game (Ambrose was charging in with the setting sun right behind his bowling arm), but Stuart Law, Michael Bevan and Ian Healy all batted really well and we managed to set them 208 to win. It looked all over when they reached 2–165 in the 42nd over, but Glenn McGrath and Shane Warne were magnificent, Mark Taylor’s leadership was inspirational and Damien Fleming was nerveless at the end. Having failed earlier in the game, my contribution was obviously minimal, but I was very proud of one piece of fielding I completed near the death, when I turned a four into a three with a diving save on the boundary. At that point, every run mattered but I still wasn’t quite sure how I managed it — the only explanation being the adrenalin pumping through my body.

Immediately after the game, it was as if everyone needed time to take in all the drama of the final 10 overs. The mood was pretty sedate, at least until Heals got up and led us in a rousing rendition of ‘Underneath the Southern Cross’. We don’t sing our anthem after every one-day victory, but our vice-captain couldn’t resist the temptation this time. We did manage a couple of celebratory beers before we headed back to the hotel, and then back in team manager Col Egar’s room we started to party. Too quickly, though, the clock raced round to two or three o’clock, and then someone mentioned we had a final to win. So, reluctantly, we called it an early morning.

Bags had to be packed and in the hotel foyer by 10am. That was the easy bit. Then we had to get to the airport, get luggage checked in — rarely a formality at anything but the biggest Indian airports — then battle through passport checks and customs clearances because the final was to be staged in Lahore, Pakistan. It was early evening before we staggered into our new hotel, which left us with only one full day to prepare for the final. Sri Lanka, our opponents, had arrived 24 hours before us, which was a significant advantage for them. Training on that one day was a bit of a fiasco, because both teams turned up at pretty much the same time, so we each had to make do with a single net, which inevitably prolonged the session. Our pre-final team meeting was conducted in the manager’s room, which was hardly big enough for the purpose, and we based most of our strategy on how Sri Lanka had gone against us in the recent Tests and one-dayers in Australia, without taking into consideration how they’d been playing in this World Cup. Muttiah Muralitharan was still their main spinner, but Sanath Jayasuriya and Kumar Dharmasena, who’d been largely ineffective in Australia, had bowled some key overs in their quarter-final and semi-final wins. They would play key roles in the final, not least in the way they and Aravinda de Silva (normally a ‘part-time’ off-spinner) would slow our run-rate just when Tubby and I were due to press the accelerator. Sure enough they did the same in the game. We were 1–134 after 25 overs, but finished with a below par 7–241 after 50.

Of course, you’re always disappointed to get out, but how I fell in this final really nags at me. I’ll never forget how I slammed my bat into my locker when I returned to the dressing room. There is no joy in being dismissed for 45 when your job as a top-order batsman, once you’ve got that sort of start, is to go on to make a big score. As I recall it, I sensed something bad was going to happen. Tubby and I began to struggle to get their spinners away and I could feel the mood was changing. One thing I would learn about batting on the subcontinent is that, when the ball is turning, it can really hurt to lose a wicket, because it’s hard for incoming batsmen to come out and keep the scoreboard ticking over. In this instance, I was bowled at 3–152 and soon after Tubby was caught in the deep, which meant two new batsmen had to try to maintain our run-rate. That was never going to be easy.

Arguably the worst indication of our lack of preparation related to the fact that this was the first time we’d played a day–night game at Lahore. We had no idea how damp the field would become (a result of the evening dew) and when that happened the ball became desperately hard to grip. It hadn’t occurred to anyone in our camp to check if there was anything special about the local conditions. It’s too late for that final now, of course, but as a result of what happened in that World Cup final, changing conditions between day and night is one thing that is always talked about in Australian team meetings. We should have known then; we know now.

When Sri Lanka batted, we quickly broke up their opening partnership but de Silva strode out to strike a match-winning century and this time there was no amazing Aussie fightback. At least this time the two teams shook hands after the game, but then we retreated to a very sombre dressing room where we had to concede we’d been beaten by the better team on the night.

WHEN I GOT HOME and I was asked about my World Cup experience, all I wanted to talk about was the semi-final, about just how electric it was being out on the ground for those final few overs and in the rooms after the game, but when I was on my own, on the golf course or maybe in the gym, I thought mostly about the final and how empty I felt after the game.

After we lost a really big game I felt like I’d let a lot of people down: my mates, my fans, myself. And there was no quick fix; the next World Cup was more than three years away.

The difference in the mood of those two dressing rooms — one in Mohali after the semi-final; the other in Lahore after the final — was colossal. I was comforted to a degree by the knowledge that after all the stress and rancour that went with our decision not to go to Sri Lanka, we’d actually done pretty well just to get to the final, but the memory of how I felt after that defeat stayed with me. As my career unfolded, I’d enjoy many big wins and be part of some massive celebrations, but there would also be a few losses along the way that really scarred, where straight after the game and even for a few days afterwards I didn’t like being on the front line, where I wanted to be miles away. This was the first of them.

My cricket journey has been long and fulfilling. From my earliest days playing school and grade cricket right through to my last game in August 2013 in the Caribbean, I’ve enjoyed so many highs and my fair share of lows. I’ve developed lifelong friendships, been to some of the most amazing places and had the honour to captain my country. I’ve played with and against childhood idols, on all the great cricket grounds around the world, and mingled with royalty as well as the poorest of the poor. But for all these great opportunities and happenings, I’ve always tried to stay as grounded and as true as possible to myself, my family and my team-mates in everything that I’ve done.

I’ve always tried to be thinking of other people and doing what I could do to support them, of how my team-mates could improve, do better or enjoy their cricket more, as well as observing what their strengths are and how they could make them even better, plus what their weaknesses are and what I could do to help them both on and off the field. I worked really hard at this support, especially when we were on the road, when we could spend more time together.

Stepping back and looking at those around you and working out what you can do to help them is something all cricket captains, leaders or business people should do regularly. You’re only as good as the team around you.

(#ulink_7c785028-68fe-515c-8361-61ef4a91db10)

I ANSWERED THE PHONE at home a few days before Christmas. As soon as he said, ‘G’day Ricky, Trevor Hohns,’ I knew I was in trouble. It had become a standard quip among the players that the only time we heard from Trevor was when he called to say you’d been dropped.

‘We want you to go back to Shield cricket and score a hell of a lot of runs,’ he said. I was out of the Test side and the one-day squad too.

As early Christmas gifts went, this wasn’t one of the best I’d ever received.

My manager Sam Halvorsen, a Hobart-based businessman who’d been looking after me since Greg Shipperd introduced me to him in late 1994, had negotiated a number of sponsorship deals and was telling me that I was very much in demand — well, at least I was in Tasmania. All I’d done from mid-March to mid-July was keep myself fit, work on my golf handicap, raced a couple of greyhounds and had some fun. In July, I travelled to Kuala Lumpur to play for Australia in a Super 8s event and soon after that I was in Cairns and Townsville playing for Tassie in a similar tournament involving all six Sheffield Shield teams. Life was good.

I was just 22 years old and batting at three for Australia. I’d filled that position throughout the World Cup earlier in the year and with David Boon retired from international cricket I took his spot at first drop for a one-off Test against India.

After just three Tests at No. 3, I was out of favour and out of the team, confused and a little angry with the way I’d been treated. I wasn’t really sure why I’d been cast aside so quickly and still don’t know why. Some people wanted to assume it was for reasons other than cricket, but I’d done nothing to deserve that. I’ve always wondered if they were trying to teach me some sort of lesson, as if that’s the way you’re supposed to treat young blokes who get to the top quicker than most. I got sick of the number of people who wanted to kindly tell me that everyone was dropped at some stage during their career: how Boonie was dropped; Allan Border was dropped; Mark Taylor was dropped; Steve Waugh was dropped; even Don Bradman was dropped. I nodded my head and replied that I was aware of that and that I would do all I could to fight my way back into the team, but the truth was I was in a bit of disarray. It wasn’t so much a question of whether I deserved the sack but that it had come out of the blue. For the first time in my life the confidence I’d always had in my cricket ability was shaken. If someone was trying to teach me a lesson, what was it?

Years later, when I was captain, I would push for a role as a selector because I believed I should always be in a position to tell a player why they had been dropped, or what the selectors were looking for. There were a few times when I was baffled by their decisions but had to keep that to myself as nothing was to be gained by making that public and nobody was going to change the selectors’ minds. In the year after I retired I saw batsmen rotate through the team like it was a game of musical chairs. I know what this sort of treatment does to the confidence of players and I found it hard to watch from a distance. If you’re looking over your shoulder thinking this innings could be your last then you’re adding a layer of unnecessary pressure when there’s enough of that around.

A FEW MONTHS EARLIER, in late August, we’d been in Sri Lanka for a one-day tour that was notable for the ever-present security that kept reminding us of the boycott controversy of six months before and for the fact Mark Taylor was not with us because of a back injury. Ian Healy was in charge and I thought he did a good job as both tactician and diplomat, with the tour being played out without a major incident. Heals wasn’t scared to try things, such as opening the bowling against Sri Lanka with medium pacers Steve Waugh and Stuart Law rather than the quicker Glenn McGrath and Damien Fleming on the basis that Jayasuriya and Kaluwitharana preferred the ball coming onto the bat, and he also made sure the newcomers to the squad, spinner Brad Hogg and paceman Jason Gillespie, had an opportunity to show us what they could do. We did enough to make the final of a tournament that also featured India, but lost the game that mattered, against Sri Lanka, by 30 runs.

The security was ultra-tight wherever we went, to the point that a ‘decoy bus’ was employed every time we were driven from our hotel to the ground. This, to me, was just bizarre. There were two buses that looked exactly the same, with curtains closed across all the windows, and the first bus would take off in one direction, while the second went the other way. First, I couldn’t help thinking that if someone was planning to attack our bus, we were playing a form of Russian roulette. And then I’d wonder: Why are we here? Is what we’re doing really that important? If we need to be protected this closely, doesn’t that mean something is not right?

Security-wise, touring the subcontinent went to another level after the 1996 World Cup, and it’s been that way — maybe even more so — ever since. For almost my entire career, it’s been awkward to venture outside the hotel. I was one of many Aussie cricketers on tour who spent most of my time in the hotel, drinking coffee or playing with my laptop. As the internet became more accessible, a few guys became prone to give their TAB accounts a workout, focusing on the races and footy back home. Soldiers or policemen carrying machine guns outside elevators, even sometimes outside individual rooms, became a customary sight. Guests were not allowed on floors other than their own, outsiders were kept away from the hotel lobby. For the 2011 World Cup, friends and family needed a special pass if they wanted to get through the hotel’s front door. It was life in a fishbowl and not always reassuring.

Being constantly under guard did wear me down from time to time, but I don’t think it’s shortened anyone’s career. No one ever came to me frazzled, to say, ‘I can’t cope with this anymore, I’m giving touring away.’ That thought never once occurred to me. Rather, a little incongruously, the guys who have retired in recent times have almost to a man kept returning to India to play Twenty20, pursue business opportunities and to seek help for their charities.

I guess, in the main, we became used to it.

A MONTH AFTER THE AUGUST 1996 Sri Lanka tour, we were in India for a tour involving one Test match and an ODI tournament also involving the home team and South Africa. I started promisingly, scoring 58 and 37 not out on a seaming deck in a three-day tour game at Patiala, but after that I struggled against the spinners on a succession of slow wickets. However, I wasn’t the only one to have an ordinary tour, which was reflected in our results: we didn’t win a game.

During the month we were in India, we criss-crossed the country, playing important games in some relatively minor cricket centres, covering way too many kilometres and staying in some ordinary hotels. It was one of my least enjoyable tours, and not just because I didn’t score many runs. To get from Delhi to Patiala and back, for example, we spent upwards of 13 hours on a poorly ventilated and minimally maintained train, and then stayed in accommodation that was frankly putrid. The Indian Board had arranged the warm-up match for us and said we’d enjoy the short trip through some lovely countryside, but it took forever and the train was so filthy you couldn’t see through the windows. We’ve been stitched-up a few times over the years with travel arrangements — such as when we’ve been on planes that have flown over the city we’re going to, continued in the same direction to another airport and then we’ve landed, got off, got on another plane and flown back a few hours later — but the ‘Patiala Express’, as we sarcastically called it, was the worst of them. Tugga said it was a good ‘team-building exercise’, but he was wrong.

Complaining about these things might sound precious, but too often when we were trying to prepare for a series we were sent to play at places that had substandard facilities.

For future tours, we learned not to worry about ordeals such as this, working on the basis that it was just part and parcel of the careers we’d chosen for ourselves. There is no doubt the good times far outweighed the bad. They’d make us travel all over India for ODIs, and we’d feel they were trying to make it hard for us to win, but we’d use it as motivation: You can send us wherever you want, we’ll still find a way to win.

Most of the time we were well looked after on tour and the team hotels were the best available, but there were always exceptions. You talk to the older guys and they tell terrible stories from earlier tours. Rod Marsh says that for a whole tour of Pakistan he never drank anything apart from soft drinks and beer because there wasn’t even bottled water. The one thing as a cricketer you are most scared of is getting sick. I do remember once sitting opposite Adam Gilchrist at dinner in a hotel that is infamous in Australian cricket and seeing something that was simply unbelievable. Gilly’s meal came with a small bowl of soy sauce and when the waiter put it down there was a cockroach in it. Gilly pointed it out and the bloke just grabbed it and stuck it in his mouth and said ‘there’s nothing there’. We were absolutely horrified. The waiter was struggling to talk because he still had it in his mouth and I can tell you we couldn’t eat after that.

I came to think that it was a good indication of how the team was going if we were whingeing or fighting with each other on tour and I think you can see that from the outside too. The worse the performance on the field, the more likely you are to hear about things happening off it.

I knew the team wasn’t in great shape if there was a lot of griping or squabbling going on. This India tour might have offered proof of that — at a time when we weren’t sure where our next win was coming from, on a flight from Indore to Bangalore after about three weeks of touring, I was involved in a dust-up with Paul Reiffel. I still think the catalyst for the blue remains one of the funnier things I’ve seen while travelling with the team, but the result was anything but amusing and I regret my part in it. We’d just lost our opening game of the one-day tournament and I was sitting across the aisle from Pistol when they brought out our meals. There was a very old Indian fellow on the other side of him, and I could see this gentleman trying to open a tomato-sauce satchel by twisting it this way and squeezing it that way. It was one of those situations where you know what’s about to happen. Finally, he decided to bite the satchel open … at the same time he kept squeezing … and, sure enough, the sauce flowed all over Pistol. Our pace bowler, who’d go on to become an international umpire, cried out in a mix of anger and anguish, while I couldn’t help but laugh out loud.

‘Tone it down, Punter,’ he said to me, and then he started cleaning himself up.

After a couple of minutes, Pistol and his sparring partner sat down to continue their meals. Everything was fine until the man decided to try to read a newspaper while he tucked into his curry, at which point, he knocked his cup of water straight into Pistol’s lap. Again, Pistol’s cries of dismay were heard around the plane, while I just lost it completely.

Maybe you had to be there, or perhaps I’m just a bloke with no compassion …

I tried to rein myself in, but I couldn’t. Pistol was spewing, but he couldn’t take his rage out on the old bloke. ‘What are you laughing at?’ he snarled at me, to which I rather naively replied, ‘What do you think I’m laughing at?’

Pistol went to tap either the top of my head or the top of my seat, as a way of underlining the fact he wasn’t happy, but he missed his target and clipped me across the mouth. Now, I wasn’t laughing; instead I tried to stand and confront him, but I had my seat belt on so I couldn’t get up and suddenly I was looking like a goose. Embarrassed and angry, when I finally got to my feet I went to grab him by the scruff of the neck, which was an over-the-top reaction, but where I come from you never hit someone unless you want a reaction, and he’d hit me. A few of the boys had to come between us and settle us down, with more than one of them reminding us that the Australian reporters covering the tour were also on the plane. Pistol was happy to let it go but — ridiculously, thinking about it now — I was not, and a little while later, as we waited in the aisle to disembark, I said just loud enough for him to hear, ‘You wait till we get off this plane.’

I’d scored 35 batting at three in the game against South Africa we’d played before the flight, and Pistol had opened the bowling, but we were both dropped for our next game. Tubby brought the two of us together and told us that while he understood that touring isn’t always easy, and inevitably blokes can get on each other’s nerves occasionally, we had to be smarter than to get into a fight in such a public place. When I stopped to think about how I’d reacted, I realised I’d totally underestimated how much the stress of travelling back and forwards was getting to me. Recalling the incident now, it’s amazing it never made the papers but those were different times. A great irony for me is that Pistol is a terrific bloke, someone I like and just about the last person I would have imagined myself fighting. Except for this one time, we always got on really well.

I WAS HAPPY to get home, and this showed in my only Shield game before the start of our Test series against the West Indies, when I had a productive game against WA at the beautiful bouncing WACA. I was duly picked to bat at three for the first Test in Brisbane, and at the pre-game team meeting Tubby underlined the same points he’d made before the celebrated series in the Caribbean: how we mustn’t be intimidated by them; how we had to be aggressive; how the blokes who like to hook and pull had to keep playing those shots.

My ‘baptism of fire’ came quickly enough, as I was in on the first morning when there were only four runs on the board, after their captain, Courtney Walsh, sent us in and new opener Matthew Elliott (in for Michael Slater) was out for a duck. At lunch I was 56 not out, with Tubby on 19, and I was flying. Ambrose, Walsh and Bishop had all tested me with plenty of ‘chin music’ but I went after them, and it was one of the most exhilarating innings of my life, right from the moment the first ball I faced kicked up at me and I jabbed it away to third man for four. All my early runs came through that area, and then I put a bumper from their fourth quick, Kenny Benjamin, into the crowd at deep fine leg. When Bishop tried a yorker I drove him through mid-off for four, and then I did the same thing to Ambrose, while Walsh fired in another bouncer and I hooked past the square-leg umpire for another four. On the TV, Ian Chappell described me as the ‘ideal No. 3’ but others may have been thinking differently.

Benjamin came back and I moved into the 80s with a drive past mid-on for another four. I was thinking not so much about making a hundred as going on to a very big score, but then he pitched one short of a length but moving away, and I hit my pull shot well but straight to Walsh at mid-on. It was a tame way to get out, and I had one of those walks off the ground where I was pretty thrilled with my knock but upset that it had ended too soon, so I was hardly animated as I acknowledged the crowd before disappearing into the dressing room. I made only 9 in our second innings, caught down the legside, but we went on to win the game by 123 runs and I felt my counter-attack on the first day had played a significant part in the victory.

My bowling had also played a part, after Steve Waugh strained a groin in the Windies’ first innings. I was called on to complete his over and with my fifth medium-paced delivery I had Jimmy Adams lbw. This meant my Test career bowling figures now looked this way: 29 balls, two maidens, two wickets for eight.

A week later we were in Sydney for the second Test, but I suffered a double failure, out for 9 and 4, both times playing an ordinary shot. But we won again to take a firm grip on the series — the only way we could lose the Frank Worrell Trophy was for the West Indies to win the three remaining games. I had a month to prepare for the Boxing Day Test and in that time I played in three ODIs, for scores of 5, 44 and 19 run out, a Shield match against Victoria in Hobart, where I managed 23 and 66, and a tour game against Pakistan (the third team in the World Series Cup) where I scored 35 and we won by an innings. Sure, none of this was special, but it wasn’t catastrophic either so I didn’t expect the bloke on the other end of the line to be chairman of selectors Trevor Hohns when I answered the phone at home a few days before Christmas.

When he told me I was out of both sides I was so stunned I didn’t say much. I certainly didn’t complain, but I didn’t ask any questions either. Matthew Elliott was hurt and Michael Bevan and I had been omitted, with Matthew Hayden, Steve Waugh (returning from injury) and Justin Langer coming into the side. Lang would bat at three, which might have given the best clue as to the team hierarchy’s thinking. I would come to learn that both Trevor and Mark Taylor were reasonably conservative in much of their cricket thinking, and I think their concept of the ideal No. 3 was a rock-solid type, what David Boon had given them for the previous few years. At this stage of his career, Lang was like that, whereas my natural instinct was to be more aggressive. Looking back, given the attacking way I played when I was 21, I probably needed to score a lot more runs than what I did at that time to keep the spot for long. But the truth is I didn’t know then why I was dropped, because they never told me, and I still don’t know now. I was never told anything specific about my original promotion up the order — it just seemed like a logical progression — or why I was abandoned so quickly. If they thought I had weaknesses in my technique or my character, why did they move me to the most important position in the batting order in the first place?

Almost immediately after Trevor’s phone call, Mum and Dad took me out to the golf club, in part because they thought we’d escape the local media there. It was good to get out of the house but Launceston is not that big a city and the reporters were waiting behind the ninth green. Over the years, journos learned that if they wanted to find me the golf course was the best place to look. This time, I think I handled it okay and they were sympathetic with their questions, but it was almost bizarre as I watched them walk away. I felt like calling out to them, Don’t forget about me!

One of the things that nagged at me was that I had been keen to bat at three when Tubby offered me the opportunity. But maybe I signed my ‘death warrant’ when I took on the challenge. Perhaps it would have been smarter to stay at six to give me more time to settle into Test cricket. Boonie had told me I should bat down the order for a couple of years, had even made me bat at four in that Shield game after the second Test, and maybe I should have listened to him. In fact, a lot of thoughts spun through my head, none of them pretty, all of them amplified because I hadn’t seen the sack coming. To tell you the truth, I wasn’t quite sure how to feel … sorry for myself … determined to get back … embarrassed … distraught … all of the above …

All I ever wanted to do was play for Australia … and now I’ve blown it.