По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

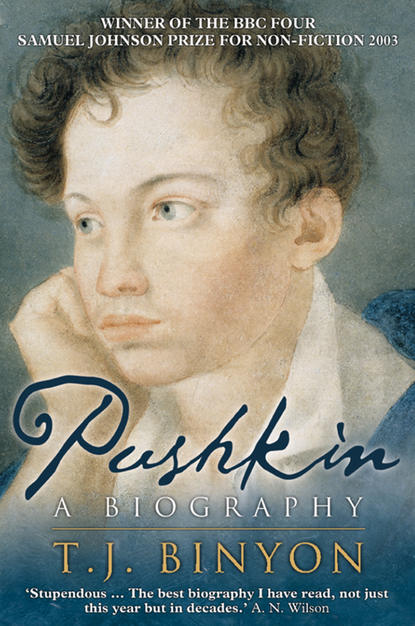

Pushkin

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

(#litres_trial_promo)

Pushkin gambled constantly, and as constantly lost, as a result having to resort to money-lenders. He played frequently with Nikita Vsevolozhsky, whose deep pockets enabled him to bear his losses. Pushkin, less fortunate, was compelled to stake his manuscripts, and in 1820 lost to Vsevolozhsky a collection of poems which he valued at 1,000 roubles. When, four years later, he was preparing to publish his verse, he employed his brother Lev to buy the manuscript back. Vsevolozhsky generously asked for only 500 roubles in exchange, but Pushkin insisted that the full amount should be paid. âThe second chapter of âOneginâ/ Modestly slid down [i.e., was lost] upon an ace,â Ivan Velikopolsky, an old St Petersburg acquaintance, recorded in 1826, adding elsewhere: âthe long nails of the poet/Are no defence against the misfortunes of play.â

(#litres_trial_promo) And in December of the same year, when Pushkin was staying at a Pskov inn to recover after having been overturned in a carriage on the road from Mikhailovskoe, he told Vyazemsky that âinstead of writing the 7th chapter of Onegin, I am losing the fourth at shtoss: itâs not funnyâ.

(#litres_trial_promo) Another favourite opponent at the card-table was Vasily Engelhardt, described by Vyazemsky as âan extravagant rich man, who did not neglect the pleasures of life, a deep gambler, who, however, during his life seems to have lost more than he wonâ. âPushkin was very fond of Engelhardt,â he adds, âbecause he was always ready to play cards, and very felicitously played on words.â

(#litres_trial_promo) In July 1819, having recovered from a serious illness â âI have escaped from Aesculapius/Thin and shaven â but aliveâ â Pushkin, who was leaving for Mikhailovskoe to convalesce, in a verse epistle begged Engelhardt, âVenusâs pious worshipperâ, to visit him before his departure.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The cold he had caught while, as Turgenev reported, standing outside a prostituteâs door, had turned into a more serious illness â it seems likely to have been typhus. On 25 June his uncle wrote from Moscow to Vyazemsky in Warsaw: âPity our poet Pushkin. He is ill with a severe fever. My brother is in despair, and I am extremely concerned by such sad news.â

(#litres_trial_promo) James Leighton, the emperorâs personal physician, was called in. He prescribed baths of ice and had Pushkinâs head shaved. After six weeksâ illness Pushkin recovered, but had to wear a wig while his own hair grew again. This was not Pushkinâs only illness, though it was the most severe, during these years in the unhealthy â both in climate and amusements â atmosphere of St Petersburg. Besides a series of venereal infections, he was also seriously ill in January 1818: âOur poet Aleksandr was desperately ill, but, thank God, is now better,â Vasily Pushkin informed Vyazemsky.

(#litres_trial_promo) During this illness Elizaveta Schott-Schedel, a St Petersburg demi-mondaine, had visited him dressed as an hussar officer, which apparently contributed to his recovery. âWas it you, tender maiden, who stood over me/In warrior garb with pleasing gaucherie?â he wonders, pleading with her to return now he is convalescent:

Appear, enchantress! Let me again glimpse

Beneath the stern shako your heavenly eyes,

And the greatcoat, and the belt of battle,

And the legs adorned with martial boots.

(#litres_trial_promo)

âPushkin has taken to his bed,â Aleksandr Turgenev wrote the following February;

(#litres_trial_promo) a year later, in February 1820, he was laid up yet again. Unpleasant though the recurrent maladies were, the periods of convalescence that followed afforded him the leisure to read and compose: he can have had little time for either in the frenetic pursuit of pleasure that was his life when healthy. The first eight volumes of Karamzinâs History of the Russian State had come out at the beginning of February 1818. âI read them in bed with avidity and attention,â Pushkin wrote. âThe appearance of this work (as was fitting) was a great sensation and produced a strong impression. 3,000 copies were sold in a month (Karamzin himself in no way expected this) â a unique happening in our country. Everyone, even society women, rushed to read the History of their Fatherland, previously unknown to them. It was a new revelation for them. Ancient Russia seemed to have been discovered by Karamzin, as America by Columbus.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

The friendship between Pushkin and the Karamzins, begun at Tsarskoe Selo, had continued in St Petersburg. During the winter of 1817â18 he was a frequent visitor to the apartment they had taken in the capital on Zakharevskaya Street; at the end of June 1818 he stayed with them for three days at Peterhof, sketched a portrait of Karamzin, and, with him, Zhukovsky and Aleksandr Turgenev went for a sail on the Gulf of Finland. He was in Peterhof again in the middle of July, and, when the Karamzins moved back to their lodging in Tsarskoe Selo, visited them three times in September. At the beginning of October they took up residence in St Petersburg for the winter, staying this time with Ekaterina Muraveva on the Fontanka. Pushkin visited them soon after their arrival, but then the intimacy suddenly ceased: apart from two short meetings at Tsarskoe Selo in August 1819 there is no trace of any lengthy encounter until the spring of 1820. During this period Pushkin composed a biting epigram on Karamzinâs work:

In his âHistoryâ elegance and simplicity

Disinterestedly demonstrate to us

The necessity for autocracy

And the charm of the knout.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Shortly after Karamzinâs death on 22 May 1826 Vyazemsky wrote to Pushkin in Mikhailovskoe: âYou know the sad cause of my journey to Petersburg. Although you are a knave and have occasionally sinned with epigrams against Karamzin, in order to extract a smile from rascals and cads, without doubt you mourn his death with your heart and mind.â

(#ulink_4292cf69-7728-5236-a78e-66317fdc33a1) âYour short letter distresses me for many reasons,â Pushkin replied on 10 July. âFirstly, what do you mean by my epigrams against Karamzin? There was only one, written at a time when Karamzin had put me from himself, deeply wounding both my self-esteem and my heartfelt attachment to him. Even now I cannot think of this without emotion. My epigram was witty and in no way insulting, but the others, as far as I know, were stupid and violent: surely you donât ascribe them to me? Secondly. Who are you calling rascals and cads? Oh, my dear chap ⦠you hear an accusation and make up your mind without hearing the justification: thatâs Jeddart justice. If even Vyazemsky already etc., what about the rest? Itâs sad, old man, so sad, one might as well straightaway put oneâs head in a noose.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

The ârascals and cadsâ of Vyazemskyâs letter are the Decembrists. Their trial had opened a month earlier, on 3 June: no wonder he should sadly reproach Vyazemsky for prematurely passing sentence on them. However, as his letter makes clear, though the epigram is a political attack, his rejection by Karamzin was on personal, not political grounds. In April 1820 Karamzin wrote to Dmitriev, âHaving exhausted all means of knocking sense into his dissolute head, I already long ago abandoned the unfortunate fellow to Fate and to Nemesis.â

(#litres_trial_promo) What wounded Pushkin so deeply was an unsparing castigation of his follies, followed by banishment into outer darkness.

The performance at the Bolshoy has ended, and Eugene hurries home to change into âpantaloons, dress-coat, waistcoatâ (I, xxvi) â probably a brass-buttoned, blue coat with velvet collar and long tails, white waistcoat and blue nankeen pantaloons or tights, buttoning at the ankle â before speeding in a hackney carriage to a ball. This has already begun; the first dance, the polonaise, and the second, the waltz, have taken place; the mazurka, the central event of the ball, is in full swing and will be followed by the final dance, a cotillion.

The ballroomâs full;

The musicâs already tired of blaring;

The crowd is busy with the mazurka;

Around itâs noisy and a squash;

The spurs of a Chevalier guardsman jingle;

(#ulink_83d0cfef-f3a2-55a9-88e0-e367f3d96c40)

The little feet of darling ladies fly;

After their captivating tracks

Fly fiery glances,

And by the roar of violins are drowned

The jealous whispers of modish wives.

(I, xxviii)

âIn the days of gaieties and desires/I was crazy about ballsâ (I, xxix), wrote Pushkin: for the furtherance of amorous intrigue they were supreme. He was simultaneously both highly idealistic and deeply cynical in his view of and attitude towards women. In a letter to his brother, written from Moldavia in 1822, full of sage and prudent injunctions on how Lev should conduct his life â none of which Pushkin himself observed â he remarked: âWhat I have to say to you with regard to women would be perfectly useless. I will only point out to you that the less one loves a woman, the surer one is of possessing her. But this pleasure is worthy of an old 18th-century monkey.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Though he fell violently in love, repeatedly, and at the least excuse, he never forgot that the objects of his passion belonged to a sex of which he held no very high opinion. âWomen are everywhere the same. Nature, which has given them a subtle mind and the most delicate sensibility, has all but denied them a sense of the beautiful. Poetry glides past their hearing without reaching their soul; they are insensitive to its harmonies; remark how they sing fashionable romances, how they distort the most natural verses, deranging the metre and destroying the rhyme. Listen to their literary opinions, and you will be amazed by the falsity, even coarseness of their understanding ⦠Exceptions are rare.â

(#litres_trial_promo) The hero of the unfinished A Novel in Letters echoes these views. âI have been often astonished by the obtuseness in understanding and the impurity of imagination of ladies who in other respects are extremely amiable. Often they take the most subtle of witticisms, the most poetic of greetings, either as an impudent epigram or a vulgar indecency. In such a case the cold aspect they assume is so appallingly repulsive that the most ardent love cannot withstand it.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

Pushkinâs first St Petersburg passion was Princess Evdokiya Golitsyna, whom he met at the Karamzins in the autumn of 1817. This thirty-seven-year-old beauty, known, from her habit of never appearing during the day, as the princesse nocturne, had been married in 1799, at the behest of the Emperor Paul and against her wishes, to Prince Sergey Golitsyn. After Paulâs death, however, she was able to leave her husband and lead an independent, if somewhat eccentric life at her house on Bolshaya Millionnaya Street. âBlack, expressive eyes, thick, dark hair, falling in curling locks on the shoulders, a matte, southern complexion, a kind and gracious smile; add to these an unusually soft and melodious voice and pronunciation â and you will have an approximate understanding of her appearance,â writes Vyazemsky, one of her admirers. At midnight âa small, but select company gathered in this salon: one is inclined to say in this temple, all the more as its hostess could have been taken for the priestess of some pure and elevated cultâ.

(#litres_trial_promo) Here the conversation would continue until three or four in the morning. In later life her eccentricities became more pronounced; in the 1840s she mounted a campaign against the introduction of the potato to Russia, on the grounds that this was an infringement of Russian nationality.

âThe poet Pushkin in our house fell mortally in love with the Pythia Golitsyna and now spends his evenings with her,â Karamzin wrote to Vyazemsky in December 1817. âHe lies from love, quarrels from love, but as yet does not write from love. I must admit, I would not have fallen in love with the Pythia: from her tripod spurts not fire, but cold.â

(#ulink_f215854b-4a17-5b35-ad52-e5bbb4fbf53f)

(#litres_trial_promo) For some months he was deeply in love with her. Sending her a copy of âLiberty. An Odeâ, he accompanied the manuscript with a short verse: