По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

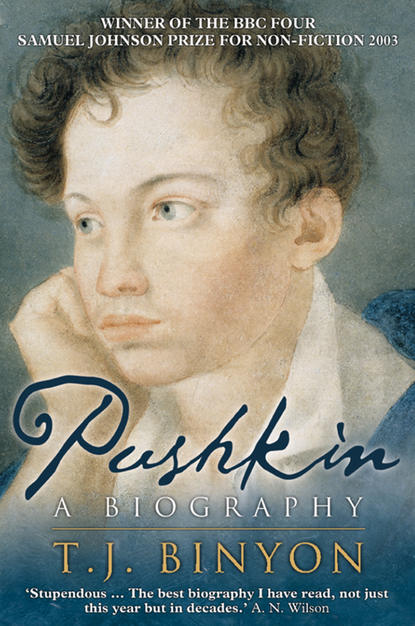

Pushkin

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

(#litres_trial_promo) It was a generous gesture, acknowledging Pushkinâs graceful and affectionate parody of Zhukovskyâs own work, âThe Twelve Sleeping Maidensâ, within the poem. Pushkin later regretted the imitation: âIt was unforgivable (especially at my age) to parody, for the amusement of the mob, a virginal, poetic creation,â he wrote.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Ruslan and Lyudmila opens in Kiev, at the feast given by Prince Vladimir to celebrate the marriage of his daughter, Lyudmila, to Ruslan. The couple repair to the bridal chamber, but, before their union can be consummated, Lyudmila is carried away by the wizard Chernomor, a hunchbacked dwarf with a magic nightcap. After many adventures Ruslan vanquishes Chernomor and brings his bride back to Kiev, routing an army of Pechenegs that is besieging the city.

Portions of the first and third cantos of the poem appeared in periodicals â the Neva Spectator and Son of the Fatherland â in 1820, and the whole poem was published as a separate edition at the end of July, after Pushkinâs departure for the south: a paperback of 142 pages, selling for ten roubles (fifteen if printed on vellum). It was Pushkinâs first published book. Earlier, in 1818 and 1819, he had tried to raise interest in a subscription edition of his poems, employing his brother Lev and Sergey Sobolevsky to sell tickets. Some had been sold (Zhukovsky had taken a hundred), but the enterprise had collapsed after the loss of the manuscript at cards to Vsevolozhsky. Before leaving St Petersburg he entrusted the manuscript of Ruslan and Lyudmila to Zhukovsky, Lev and Sobolevsky, who prepared it for publication: a difficult task in the case of canto six, since Pushkin had not had time to produce a fair copy. Gnedich took charge of the bookâs production: he was experienced in these matters, having already acted as publisher for a number of authors. He was, however, a sharp operator. In 1817 he agreed to publish a work by Batyushkov, but insisted that the poet be responsible for any loss the book might make, and, when it proved surprisingly popular, passed on to him only two thousand roubles out of the fifteen thousand the book made. He was to be similarly sharp in dealing with Pushkin and, even by publishersâ standards, dilatory: Pushkin first saw a copy of Ruslan and Lyudmila on 20 March 1821, some eight months after its publication. The entire print-run of the work was bought by Ivan Slenin, one of the largest book-sellers in St Petersburg. Gnedichâs production costs were therefore immediately covered; it has been calculated that his profit was in the region of six thousand roubles, of which Pushkin received only fifteen hundred. The poem proved extraordinarily popular; the edition soon sold out, after which copies changed hands for the unheard-of price of twenty-five roubles. And in December 1821 the imperial theatre in Moscow put on Ruslan and Lyudmila, or the Downfall of Chernomor, the evil magician, a âheroico-magical pantomine balletâ in five acts, adapted by A. Glushkovsky, with music by F. Scholz: in order to help the audience in the comprehension of the plot, placards were exhibited on stage with inscriptions such as: âTremble, Chernomor! Ruslan approaches.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

In July 1820, in the south, Pushkin wrote an epilogue to the poem, and for the second edition in 1828 added the famous and extraordinary prologue (written at Mikhailovskoe in 1824), one of his finest poems, the first line of which â âOn the sea-shore stands a green oakâ

(#litres_trial_promo) â haunts Masha Prozorova in Chekhovâs Three Sisters. For this edition he also, perhaps mistakenly â but no doubt sensibly, in view of his situation at the time â toned down some of the more risqué passages of the first version. The loss of Chernomorâs attempted seduction of Lyudmila at the end of the fourth canto is particularly to be regretted: a scene which has been claimed to represent Pushkinâs view of the marital relations between an ill-matched St Petersburg couple â the seventy-one-year-old Count Stroinovsky and his eighteen-year-old wife, Ekaterina Butkevich.

In October 1820 A.A. Bestuzhev, a lieutenant in the Life Guards Dragoons, later an extremely popular short-story writer under the pseudonym Marlinsky, another habitué of Shakhovskoyâs garret, wrote to his sister Elena: âOn account of Pushkinâs poem Ruslan and Lyudmila a terrible ink war has started up here â idiocy upon idiocy â but the poem itself is good.â

(#litres_trial_promo) The war had begun in June with an article in the Herald of Europe, directed chiefly against Zhukovsky, but deploring en passant the intrusion into literature of such coarse material as the published extracts from Pushkinâs poem. âLet me ask you: what if somehow [â¦] a guest with a beard, in a peasant coat and bast shoes were to worm his way into the Moscow Noble Assembly, and were to cry in a loud voice: Greetings, folk! Would one admire such a rascal?â

(#litres_trial_promo) In August and September Voeikov, a member of Arzamas, who hence might have been expected to be on Pushkinâs side, devoted four long and tedious articles to the poem in Son of the Fatherland, in the last of which he accused Pushkin of using âpeasantâ rhymes, and âlowâ language, and of one expression remarked âhere the young poet pays tribute to the Germanicized taste of our timesâ, a dig at romanticism and Zhukovsky.

(#litres_trial_promo) The Neva Spectator now chimed in, complaining of the âinsignificant subjectâ, taking particular exception to the intrusion of a contemporary narrator into the narrative, and deploring the presence of âscenes, before which it is impossible not to blush and lower oneâs gazeâ; these possibly encouraged revolution, and were certainly unsuited to poetry.

(#litres_trial_promo) In September an article signed N.N. â thought then to be by Pushkinâs friend Katenin, but now known to have been written, under Kateninâs influence, by a fellow-officer in the Preobrazhensky Life Guards, Dmitry Zykov â in Son of the Fatherland concentrated on what the author saw as the implausibilities of the poem: âWhy does Ruslan whistle when he sets off? Does this indicate a man in despair? [â¦] Why does Chernomor, having got the magic sword, hide it on the steppe, under his brotherâs head? Would it not be better to take it home with him?â In October Aleksey Perovsky came to the poemâs defence with two witty articles in Son of the Fatherland, in which he took issue both with Voeikov and Zykov: âUnfortunate poet! Hardly had he time to recover from the severe attacks of Mr V., when Mr N.N. appeared with a pack full of questions, each more subtle than the other! [â¦] Anyone would think that at issue was not a Poem, but a criminal offence.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

Most of these critical remarks, though annoying, were too ludicrous to be taken seriously; and the success of the work was wonderfully consoling. However, Pushkin was hurt when Dmitriev, whom he had known since childhood, commented to Vyazemsky â who passed the remark on â of the poem: âI find in it much brilliant poetry, lightness in the narrative: but it is a pity that he should so often lapse into burlesque, and a still greater pity that he did not use as an epigraph the well-known line, slightly amended: âA mother will forbid her daughter to read itâ.

(#ulink_1f630a26-aa4e-52d9-901b-b11d62806d56) Without this caution the poem will fall from a good motherâs hand on the fourth page.â

(#litres_trial_promo)

Pushkin hardly conceals his multiple borrowings in the poem: from Zhukovsky, from Ossian, from the Russian folk epic, and, above all, from Ariosto and Voltaire. The first two are the least important: Zhukovskyâs influence is limited to the parody of âThe Twelve Sleeping Maidensâ, where Pushkinâs lively irreverence, his delight in the physical, his attention to detail are an invigorating contrast to Zhukovskyâs somewhat plodding gothic narrative with its lack of specificity. From Ossian Pushkin borrows a line from the poem âCarthonâ, âA tale of the times of old! The deeds of days of other yearsâ, which, translated, forms the first and last two lines of his poem.

(#litres_trial_promo) He seems, too, to have adapted some names from this poem for his characters: Moina, the mother of Carthon, becoming Naina, and Reuthamir, her father, Ratmir. His debt to the Russian folk epic, the bylina, is somewhat greater. The poem employs the traditional setting of the Kievan bylina cycle: the court of Prince Vladimir in Kiev, and follows the folk epic in referring to the prince as âVladimir the Sunâ, a legendary figure who is seen as an amalgam of the Kievan rulers Vladimir I (d. 1015) and Vladimir II Monomakh (d. 1125). Pushkin, however, no doubt as a result of his reading of Karamzin, is more historically correct than his model: the nomadic army, one of a succession of invaders from the East, which besieges Kiev in Ruslan and Lyudmila, is that of the Pechenegs, against whom Vladimir I fought; in the byliny such enemies are usually generalized as Tatars.

But Pushkin had no intention of creating a modern bylina: he makes no use of the mythology of the genre, nor of its traditional heroes. Instead, he invents his own characters, who, on leaving Vladimirâs court, leave the world of the bylina and abruptly find themselves confronting the crenellated battlements of a Western European castle. Neither was he inclined to write a Russian heroic epic, as many wished him to do: the tone of Ruslan and Lyudmila is determinedly mock-heroic throughout, as Pushkinâs comic treatment of the most obviously heroic episodes demonstrates, such as Ruslanâs defeat of the Pecheneg army:

Wherever the dread sword whistles,

Wherever the furious steed prances,

Everywhere heads fly from shoulders

And with a wail rank on rank collapses;

In one moment the field of battle

Is covered with heaps of bloody bodies,

Living, squashed, decapitated,

With piles of spears, arrows, armour.

(VI, 299â306)

The models to which Ruslan and Lyudmila owes most are Ariostoâs Orlando Furioso (1532) â which Pushkin would have read in a French prose version â and Voltaireâs La Pucelle (1755), itself modelled on Ariosto, though Pushkinâs work is on a much smaller scale than its predecessors.

(#ulink_664824b5-1d51-5eb5-b7e5-af000ce72827) Like them, he will begin a canto with general remarks, often addressed to his readers, and tantalizingly break off the narration at a crucial moment to turn to the adventures of another character. His narrator, like those of Ariosto and Voltaire, is not contemporary with the events, but of the present day, intrusive, digressive, and constantly ironizing at the expense of the characters, the plot and its devices. Both Ariosto and Voltaire claim that their works are based upon actual chronicles; composed, in Ariostoâs case, by Tripten, Archbishop of Reims, a legendary figure; and, in Voltaireâs, by lâabbé Tritême, a real figure, but innocent of the authorship foisted upon him. Pushkin follows suit with another ecclesiastic, a âmonk, who preserved/For posterity the true legend/Of my glorious knightâ (V, 225â7).

It is here, however, that Pushkin parts company with his predecessors. Fantastic as the events in both Ariosto and Voltaire are, the narratives rest on some slight residue of fact, and the backgrounds against which the action unfolds have, for the most part, some semblance of geographical plausibility. With the exception of the Kievan court, however, Ruslan and Lyudmila is pure fantasy, set in a land of pure romance. If Ariostoâs aim is to please his patrons by extolling the glorious, if legendary past of the House of Este, and Voltaireâs to satirize â powerfully, if often crudely â religion, superstition and monarchical rule, Pushkinâs is far more intimate, as his poem is on a far more intimate scale: to entertain his friends and social acquaintances. In his asides, foreshadowing Eugene Onegin, he brings himself and St Petersburg society into the poem. When he compares Lyudmila with âsevere Delfiraâ, who âbeneath her petticoat is a hussar,/Give her only spurs and whiskers!â (V, 15â16), he is referring to Countess Ekaterina Ivelich, a distant relation of the Pushkins, who lived near them on the Fontanka, and was described by Delvigâs wife as âmore like a grenadier officer of the worst kind than a ladyâ.

(#litres_trial_promo) He begins, too, at first timidly, to experiment with a literary device that was to become a favourite, both in verse and in prose: he plays with his readers, teasing them and subverting their expectations.

When, in the third stanza of Eugene Onegin, he calls on the âfriends of Lyudmila and Ruslanâ to meet his new hero, he is not merely attempting to capitalize on the popularity of the earlier poem, but hinting that those who had enjoyed it would also enjoy his latest work: despite the obvious dissimilarities â one a mock epic, set in a fabulous past, the other a contemporary novel in verse â the two share a common tone. Batyushkov was right when he spoke of the poemâs âtaste, wit, invention and gaietyâ; to these he could have added youthful exuberance, charm, and the effortless brilliance of the verse: characteristics which are also those of Eugene Onegin. The poem improves as it continues, and is at its best when Pushkinâs fantasy is least constrained by the demands of the plot or a traditional setting: Prince Ratmir in the hands of his female bath attendants, and Lyudmila in Chernomorâs castle and garden are episodes which outshine the rest.

One of the most colourful characters of this time â an age when they were not in short supply â was Count Fedor Tolstoy (his first cousin, Nikolay, was the father of Leo Tolstoy

(#ulink_56bff66a-0610-5d90-81e9-c16b344b110a)). Born in 1782, he joined the Preobrazhensky Life Guards, where he soon made a reputation for himself as a fire-eater, duellist â he was said to have killed eleven men in duels in the course of his life â and cardsharp. In 1803 he was a member of an embassy to Japan, taken there by Admiral Krusenstiern on his circumnavigation of the world. Tolstoy made himself so obnoxious on board that Krusenstiern abandoned him on one of the Aleutian Islands â together with a pet female ape, which he may later have eaten. Crossing the Bering Straits, he wandered slowly back through Siberia, arriving in St Petersburg at the end of 1805: hence his nickname âthe Americanâ. Coincidentally, Wiegel, who, as a member of Count Golovkinâs embassy to China, was travelling in the opposite direction in the summer of that year, met him at a post-station in Siberia. âWhat stories were not told about him! As a youth he was supposed to have had a passion for catching rats and frogs, opening their bellies with a pen-knife, and amusing himself by watching their mortal agonies for hours on end [â¦] in a word, there was no wild animal comparable in its fearlessness and bloodthirstiness with his propensities. In fact, he surprised us with his appearance. Nature had tightly curled the thick black hair on his head; his eyes, probably reddened with heat and dust, seemed to us injected with blood, his almost melancholy gaze and extremely quiet speech seemed to my terrified companions to conceal something devilish.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Settling in Moscow â where in 1821 he married a beautiful gypsy singer, Avdotya Tugaeva â he spent his time gambling at the English Club, usually winning large sums through his skill in manipulating the deck. He was a close friend of Shakhovskoy â the two had been fellow-officers in the Preobrazhensky Guards â and of Vyazemsky.

âCount Tolstoy the American is here,â Turgenev wrote to Vyazemsky from St Petersburg in October 1819. âHe is staying with Prince Shakhovskoy, and therefore we will probably see each other rarely.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Pushkin, however, as a regular visitor to Shakhovskoyâs garret, soon met Tolstoy, and was soon, unwisely, playing cards with him. Noticing that Tolstoy had slipped a card from the bottom of the pack, he commented on this. âYes, Iâm aware of that myself,â Tolstoy replied, âbut I donât care to have it pointed out to me.â

(#litres_trial_promo) Whether because of this, or whether out of sheer malice, Tolstoy, on returning to Moscow, wrote a letter to Shakhovskoy in which he asserted that, on the direct orders of the tsar, Count Miloradovich, the military governor-general of St Petersburg, had had Pushkin flogged in the secret chancellery of the Ministry of the Interior. Shakhovskoy made the libel known to the frequenters of his garret. Though other friends, such as Katenin, energetically refuted it, it spread quickly through literary and social circles. Pushkin eventually learnt of it â though not of its author â from Katenin. Humiliated and infuriated, he oscillated between thoughts of suicide and of reckless defiance of authority.

Though, with Chaadaevâs help, he overcame his initial despair â âThe voice of slander could no longer wound me,/Able to hate, I was able to despiseâ

(#litres_trial_promo) â he burnt with the desire to avenge himself. In the draft of a letter to the emperor (which was never sent), composed in 1825 in Mikhailovskoe, he wrote, âthe rumour spread that I had been brought before the secret chancellery and whipped. I was the last to hear this rumour, which had become widespread, I saw myself as branded by opinion, I became disheartened â I fought, I was 20 in 1820.â

(#litres_trial_promo) There is no direct evidence that Pushkin fought a duel early in 1820 over this matter. However, in June 1822 the seventeen-year-old ensign Fedor Luginin recorded in his diary a conversation with Pushkin in Kishinev: âThere were rumours that he was whipped in the Secret chancellery, but that is rubbish. In Petersburg he fought a duel because of that.â

(#litres_trial_promo) If he did fight a duel, it has been suggested that his opponent was the poet and Decembrist Kondraty Ryleev.

(#litres_trial_promo) The conjecture is based on a letter of March 1825 from Pushkin to Ryleevâs friend Bestuzhev. âI know very well that I am his teacher in verse diction â but he goes his own way. He is a poet in his soul. I am afraid of him in earnest and very much regret that I did not shoot him dead when I had the chance, but how the devil could I have known?â

(#litres_trial_promo) He certainly met Ryleev a number of times between September 1819 and February 1820 (when Ryleev returned to his wifeâs parentsâ estate near Voronezh) and preserved a sufficiently vivid memory of him to sketch, in January 1826, his profile, with ski-jump nose, protruding lower lip and lank hair next to a portrait of Küchelbecker on a page of the manuscript of the fifth chapter of Eugene Onegin.

(#litres_trial_promo) But whether a duel did take place, and, if it did, whether Ryleev was his opponent are questions which cannot be answered without more evidence.

Pushkin did not learn that Tolstoy had been responsible for the rumours until the autumn of 1820. Then he took partial revenge with an epigram, an adaptation of which he inserted into an epistle to Chaadaev in April 1821. Tolstoy is called a âphilosopher, who in former years/With debauchery amazed the worldâs four corners,/ But, growing civilized, effaced his shame/Abandoned drink and became a card-sharp.â

(#litres_trial_promo) The poem appeared in Son of the Fatherland in August. Tolstoy had no difficulty in recognizing his portrait, and composed his own epigram in reply. âThe sharp sting of moral satire/ Bears no resemblance to a scurrilous lampoon,â he wrote, advising Pushkin to âSmite sins with your example, not your verse,/And remember, dear friend, that you have cheeks.â

(#litres_trial_promo) He too submitted his lines to the Son of the Fatherland, which, however, declined the honour of printing them.

Pushkin had no intention of avenging himself with the pen, rather than the pistol. âHe wants to go to Moscow this winter,â Luginin wrote in his diary, âto have a duel with one Count Tolstoy the American, who is the chief in putting about these rumours. Since he has no friends in Moscow, I offered to be his second, if I am in Moscow this winter, which overjoyed him.â