По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

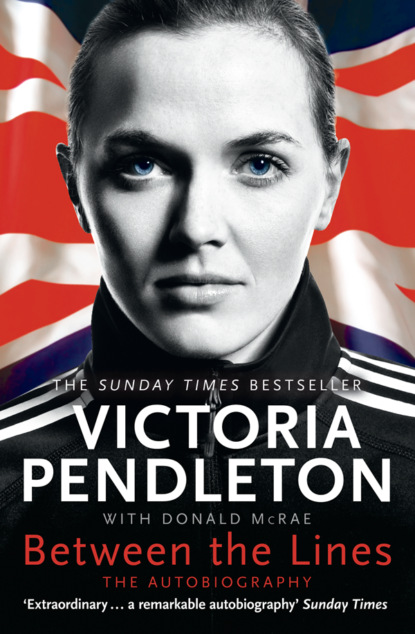

Between the Lines: My Autobiography

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Dad would not reassure me. He had his plans for the weekend and it was up to me whether I fitted in with him. If I chose not to go riding he wouldn’t say anything. He would just get up early and go out on his bike on his own. But we both knew how disappointed Dad would be if I let him down. He probably wouldn’t speak to me much all weekend.

The mute pressure Dad exerted on me felt heavier than usual. Alex, having just turned fifteen with me on 24 September 1995, had opted out of cycling. Just like Nicky before me, he saw his chance and took it. Alex knew I wasn’t going to give up. I needed Dad’s approval too much to abandon my bike. I was in for the long haul. There was no need for Alex to force himself down the same tortuous path. Dad would be happy if he had just one of us, me, to ride with him every Sunday morning. Alex quietly gave up his bike. He had other interests to explore.

‘It’s just you now, Vic,’ I said to myself. ‘Just you.’

I felt more responsible than ever for Dad’s weekend mood. I couldn’t disappoint him. And, over the prospect of an ordinary night at the movies, it felt like I had hurt him to the core.

Rather than looking forward to a modest teenage night out I felt consumed by guilt. I was letting Dad down by even thinking of me and my friends before him and the bike. Dad, without really saying anything, made me feel terrible. I also knew he was right. I would be utterly rubbish on my bike if I woke up tired on Sunday morning. It was enough of a strain hanging onto Dad racing up a hill when I had slept well and felt fresh. So, as Dad stalked off to let me think about my decision, I crumbled inside.

I went to find Mum. She was sweet and generous. We all knew what Dad was like so I should do whatever made me happy. If I fancied the pictures, I should go with my friends. Grumpy old Dad would survive.

Those sensible words were difficult to follow. The old teeming emotions rose up inside me. Dad was very good at making me feel very bad. He left me in a tight little world of fear and guilt. It was not a great place to be, not at fifteen, and so I gave in to the inevitable.

I didn’t tell Dad but, quietly, almost furtively, I disappeared upstairs to call my friends. I was sorry, I said, but I couldn’t make it to the movies after all. I’d forgotten that I had to go training with my dad in the morning. They were mystified; but they also knew I had ridden my bike every Sunday morning for so long. I felt grim, of course, for letting them down. That seemed worse to me than the fact that I was the one who would miss out on the movies and a few hours of fun.

The only good thing, after putting down the phone, was knowing that I would have felt much worse if I had gone out with my friends. Dad would have really given me the silent treatment then.

Instead, later, as I went off to bed, he sounded almost cheerful. ‘See you in the morning, Vic,’ he called out. ‘Early start for us …’

I knew my place. I would be on my bike again in the morning. I would be the girl on the hill, chasing the fleeing and distant figure of her father.

‘’Night, Mum,’ I said as I turned to climb the stairs to my room. ‘’Night, Dad …’

Alex and I began to fight more, which was normal, but horrible for me as a teenage girl. It took a long time for me to forgive him after he read my diary one night and, the next morning, waltzed straight up to a boy in our class to blurt out that I fancied him. I could have curled up and died in a dark hole but, as that option wasn’t available, I just turned the most embarrassing shade of red and seethed inside. How could boys, especially my twin brother, be so unspeakably cruel?

I survived the diary humiliation. Yet the whole world, for a while, became a desolate place. I felt unloved and misunderstood – especially at school. I really did feel like killing myself. Of course I was never going to do anything so drastic. I was far too guilty a person to seriously contemplate anything as selfish as suicide – but I harboured grim fantasies and became more withdrawn.

Most other girls in my class, at the ages of fifteen and sixteen, were going out, getting drunk and talking about boys. A few of them were already having sex. I was different. I just wanted to play sport and look a little prettier and much less skinny. It wasn’t much to ask.

I also wanted to be a germ-free girl; and so I washed my hands incessantly. It was one way of keeping the world at bay and, I guess, trying to rid myself of the stain I felt on the inside. I didn’t want to walk around and spread my germs to everyone else. At the same time I already knew that the world had enough germs of its own. So even if I was scrupulous about not passing on my bugs it became increasingly important that I did not pick up anyone else’s germs. Every time I had to open a door it became a real issue. It was impossible to use my hands, for fear of either spreading old germs or catching new germs, and so I had to stick out a foot, lean down with an elbow or, more self-consciously, use my bum to push open a door. I got into a right old state if the door could only be opened by swinging it towards me. In those difficult encounters I preferred to hang around until someone opened the door from the other side.

My hands were still exposed. They were germ-breeders and germ-magnets. The only solution was to wash them repeatedly. I scrubbed them with soap and held them under hot water until they looked red and raw. They were not so pretty, then, but at least I knew they were clean. Well, they were clean for a while until, naturally, they felt germ-ridden again.

The compulsive washing of my hands drove Dad mad. ‘That’s enough!’ he would shout. ‘Stop it.’

I got it under control after a while but, well, the germ paranoia never really went away. A grubby door handle and a public loo still unsettled me. I would do anything to avoid them. The hand-washing, however, dried up. Dad wasn’t going to allow me to get away with that for long.

It also helped that, finally, I began to make some real friends. We had little in common – apart from the obvious fact that we were the waifs and strays, the misfits left loitering far from the cool kids. We also tended to work hard and get irritated that most of our teachers seemed unable to quell the unruly mob that caused havoc in class. Those kids didn’t care about learning or working, but we did – which automatically made us even weirder to everyone else. Our weirdness bound us together.

We were just a small group at first – Cassie, Katie, Ruth, Anna, Helen and me – but by the time we reached the sixth form we had grown in confidence and numbers. Ten or eleven of us hung out together at lunchtime. We did well in class and began to feel that, rather than being the crazy outsiders, maybe we were the normal kids. Perhaps the cool kids were really the weird losers after all.

I also began to challenge Dad. At sixteen I started to question his authority just a little. I even managed, wonder of wonders, to go out on some Saturday evenings with my friends. It was never anything more outrageous than visiting the village pubs with some girls and boys, and I’d fret terribly if I missed my 10pm curfew by a few minutes. I still went riding on my bike with Dad the following morning; but life had begun to open up.

Cycling also became more successful for me. I won lots of competitions on the grass tracks of southeast England and started to enjoy the limited amount of prize money I was given after each victorious race.

Dad kept telling me that I was improving at an extraordinary rate. He thought I had the potential to be an amazing cyclist. Dad said I might be good enough to become a world champion one day.

‘Yeah, yeah, Dad,’ I said. But I was happy Dad was happy. I stopped washing my hands more than three or four times a day. They looked pale and slender again, rather than raw and puffy.

Mum still wouldn’t allow me to race on hard tracks, in case I fell and injured myself, but Dad and I dreamed up a devious plan. He was racing on the cement at Welwyn Garden City and we decided between us that I’d also have a crack at the junior event. We did not dare tell Mum. So we sneaked my bike into the boot of the car and covered it with a blanket. Mum thought I was just going to watch Dad race when we set off for Welwyn. She had no idea that I was about to make my cement-track debut.

The track at Welwyn was organized by some very officious people – in particular a grumpy woman who was furious that I climbed onto my bike from the wrong side. Even though the track was relatively flat, and without any steep inclines, she made me get off and walk around to the apparently safe side of my bike.

‘That’s how you get on your bike at Welwyn,’ she said cuttingly.

I couldn’t believe it. I was going to show her and all her sniggering cyclists. The girl who got on her bike the wrong way would destroy the field.

And I did. I won the junior race, beating boys and girls, with ridiculous ease. I made a point of getting off my bike the wrong way. I did it the grass-track way, rather than the Welwyn way.

I was getting noticed – and by more thoughtful people than just surly ladies in Welwyn. All my results, and victories, were printed in the back pages of Cycling Weekly and, incredibly, attention was being paid to my progress; and not just by Dad.

After Welwyn I started to ride against men, in handicap races. Dad and I would turn up and they would take one look at my skinny legs and my puppy-dog face and the handicapper would decide to push all the men a few more metres back. How could a puny sixteen-year-old girl hold off the muscly hulks? They were expected to hunt me down. Most of them couldn’t. At the finish line I would still be ahead. I would go up to the presentation table, collect my trophy and prize-money, smile demurely for the local photographer and go home, to Mum, where I would say, as usual, ‘Ta-Dah!’ and show her my booty.

Yet, when it came, the telephone call just about knocked me sideways. I could tell that Dad thought it was important because he looked flushed when he handed me the phone.

‘Hello?’ I said, not guessing for a moment that my life was about to change forever. I still thought of myself as the guilty and frightened girl on the hill, chasing after Dad as hard as her spindly legs could pedal. I could not believe that anyone, seriously, thought of me in a positive way.

Marshall Thomas sounded gentle and kind. He explained that he was the assistant coach of the national track team. I was amazed that we even had a British track team – let alone a coach who had actually heard of me. Marshall had been following my results. He had even seen the details of my win in Welwyn.

I didn’t tell him that I was the girl who climbed on her bike the wrong way. Too stunned to really speak, I waited for him to continue.

‘We’d like to invite you up to Manchester,’ Marshall said, ‘if you fancy having a ride at the velodrome.’

‘I’ll pass you over to my dad,’ I said helplessly, but remembering to thank him for calling.

I had no idea there was even a velodrome in Manchester; but Dad knew. His eyes shone and he smiled when he put down the phone. He looked so proud of me. The girl on the hill, the girl who once couldn’t read a map and kept washing her hands, had made her father so happy.

‘I knew it,’ he said quietly as he pulled me towards him. ‘I knew you were good …’

(#ulink_53509cec-f702-53ab-a7c2-1687d40c543d)

My bed turned into a fairground ride. I lay in the dark and clutched the mattress as I seemed to tilt up and down, round and round, in an endless loop of blurring movement. There were moments when I wanted to laugh out loud, or even say ‘woooaaahhh!’ as the room rocked.

‘God,’ I whispered to myself, ‘this is crazy shit …’

I didn’t take drugs, and I hardly drank, but an afternoon at the Manchester Velodrome left me tripping round the dizzying curves of the wooden track. Six hours had passed since I had slipped off my bike, but the wild rollercoaster ride would not leave the leaping pit of my stomach or the lurching whir of my mind. I could feel the same rolling sensations climbing high inside me, creeping up towards my buzzing brain, before racing back down again as if I was still on the bike and careering along the sharply banked track.

At first, because he was careful not to scare me, Marshall Thomas made sure I did not really notice the dizzying gradient of the velodrome. Speaking in the same quiet voice I remembered from our phone conversation, he concentrated on making me feel comfortable in this jolting new environment. I was a flat grass-track girl, with just a gritty smattering of experience on the hard cement at Welwyn Garden City.

Yet Marshall made me feel at home. He was much younger than I had expected – in his early thirties – and more low-key than Dad in his approach to cycling. He was also obviously intelligent and I liked the relaxed way in which he introduced me to the surrounding track.

The Manchester Velodrome belonged to another world. It looked strange, even beautiful, as Marshall slowly led me round the curved wooden bowl on my fixed-wheel bike. Marshall explained that the structure of the roof was based on a 122-metre, 200-tonne arch which provided unrestricted viewing for spectators. The roof was covered in aluminum, and weighed around 600 tonnes. But Marshall, like me, was more interested in the track.

The wood looked very shiny under the bright lights. Marshall said the 250m track was Britain’s first purpose-built indoor velodrome and that the wood flashing beneath us was the finest Siberian pine. Back then, in my teenage innocence, I had no idea that those smooth and gorgeous boards could tear chunks of flesh off your legs or arms as easily as a butcher might skin a rabbit.

I might have fainted if I had seen the sight I witnessed on this same track fifteen years later when, in a World Cup keirin race in 2011, the Malaysian rider Azizulhasni Awang stared in horror at his leg after a crash. Twenty centimeters of pure velodrome wood ran through his calf, like a meaty kebab stick, with the pointed ends jutting out on each side. The pain of being skewered must have been terrible. A day later, surgery removed that huge splinter in a clean excision from Awang’s calf.

Fortunately, as a sixteen-year-old schoolgirl, I was spared such grisly visions of the future. I was also blissfully unaware that Jason Queally would suffer a similar fate later that same year, in 1996. He crashed on his bike, while circling the track at 35mph, and a large chunk of wood lodged in his back. Chris Hoy revealed later that it was eighteen inches long and two inches wide. Suggesting it was ‘more like a fence post than a splinter’, Chris quipped in his dry way that, ‘Jason’s scream of “I’ve got half the fucking track in my back” was not unreasonable in the circumstances.’ It took almost 100 stitches to close the wound. I was far too naïve to imagine that splintering trauma.