По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

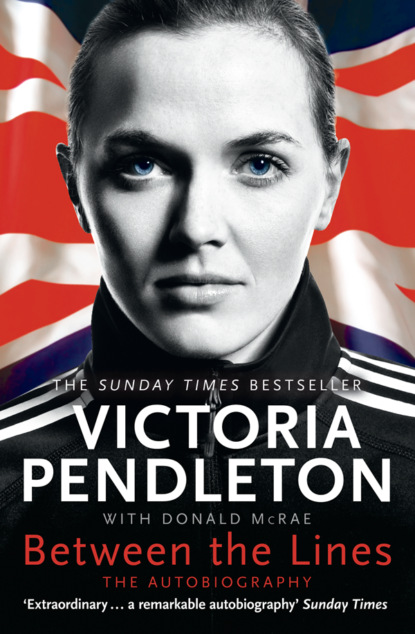

Between the Lines: My Autobiography

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I lost myself, for a long while, in a place of breath-stealing beauty. I cried and I bled high up in the Swiss Alps, above the small and pretty town of Aigle, and it took me years to heal the wound. Even now, a decade later, it’s hard for me to return there in my head. It’s a place and a time of tangled darkness and, slowly, I need to unravel it in an attempt to understand why and how everything happened.

At the far end of Lake Geneva, just eight miles southeast of Montreux, and twelve miles further from Lausanne, it took a funicular train forty minutes to travel up the alpine cliff, leading from Aigle at the base of the Alps to an idyllic setting in the mountains. I was smitten by the way the shimmering water was made to look deeper and more mysterious by the steepling trees and mountains overhead. Absorbing the view at the top, I remembered that Aigle means ‘eagle’ in French.

At that spectacular retreat above Aigle, the International Cycling Union’s sprint academy was run by Frédéric Magné. An inspirational Frenchman who had won seven World Championships on the track, Fred Magné’s most recent gold medal, and his third in the keirin, came in 2000. Two years on, in November 2002, when I left England for Switzerland, Fred had swapped success on the track for a life of coaching sprint cyclists from around the world.

The departure of Martin Barras had filled me with relief – but it left all the sprinters at the Manchester Velodrome without a coach. Jason Queally, Chris Hoy and Craig MacLean shrugged off the loss. Quick-thinking and sure of their ability, they knew they could manage together until another specialist coach was appointed.

I had just turned twenty-two and, without any other woman sprinters on the team, I followed a lonelier path into the unknown. And then, out of nowhere, salvation was offered to me in the Swiss Alps.

Two months earlier, in late September 2002, at my first World Championships, in Copenhagen, a birthday cake began the transformation. On 24 September, the day I turned twenty-two, the lights in the restaurant of our team hotel dimmed after the evening meal. A beautiful chocolate cake was then brought to my table while everyone broke into spontaneous song. ‘Happy birthday to you,’ they sang, ‘happy birthday, dear Vicky, happy birthday to you …’

Those twelve sweetly familiar words sounded strangely resonant. Rather than being clichéd or twee, they were rich and warm. As the whole squad boomed out, just for me, I felt as if I belonged. It had taken six months but, finally, I was part of the team. All my uncertainty melted away in the candlelight. I blew out all twenty-two little flames as the boys whooped. They even threw in a few more hip-hip-hoorays for me.

I knew, then, that I was on my way to Switzerland – less in farewell to the team than with the certainty that I would eventually return to Manchester as an improved cyclist after a year of being trained by Magné. The opportunity arose unexpectedly, and I heard about it soon after I ended up in an ambulance racing towards a German hospital. I had just been knocked out, literally, during the European Under-23 Track Championships.

In the sprint, against Tamilla Abassova, the Russian rider, I was sent crashing head-first into the wooden track. She turned her wheel right into mine in the midst of our race and down I went. I heard later that a doctor was on the brink of trying to resuscitate me when I opened my eyes and tried to move. But I only became fully conscious in the ambulance – where a kindly German paramedic, a large man with soft eyes, had soothed me while I moaned ‘Where am I? Where am I?’ over and over again.

Abassova powered her way to the European sprint title and my sore head was eased by the consoling words of Heiko Salzwedel, our team manager. He revealed that, before my accident, he had discussed my potential with Fred Magné. Heiko, Peter Keen and Shane Sutton were determined to push me on and, in Fred and his new sprint school, they identified a way forward. Fred recognized my raw talent and he agreed to their request. British cycling would pay for me to work with Fred – and the option was thrilling.

A chance to commit myself fully to the track encouraged me to believe my future might be shaped by cycling. My subsequent selection for the World Championships, topped off by birthday wishes the day before competition began, boosted me even more. I was on my way.

In the Worlds, however, I lost in the first heat to Svetlana Grankovskaya; and I wasn’t exactly mortified when Kerrie Meares was beaten in the final by Natallia Tsylinskaya, a multiple world champion from Belarus.

The men, meanwhile, won three gold medals. Chris Hoy became world champion in the kilo – and then, with Craig MacLean and Jamie Staff, he helped GB win the team sprint. Chris Newton also won the points race in magnificent style. Australia, as usual, headed the table with thirteen medals. Great Britain finished second, with a tally of five. We were eight medals down on the Aussies but, significantly, they had won just one more gold.

There was a gathering sense that British cycling was closing the gap. Our men looked increasingly imposing; and, even if I cut a stick-like figure amongst the hulking women from Eastern Europe and Australia, I was determined to become fitter and faster. I was now an accepted member of the national team and about to embark on a life-changing adventure in Switzerland.

In November 2002, I arrived in Geneva with Ross Edgar, from the men’s sprint squad. Ross was lovely company and it helped that he had already spent a sustained period at Fred’s school. It was also obvious that Fred, who met us at the airport, loved Ross. He might have been born in England but Ross’s mum was French and his dad was a Scot. Ross chose to represent his father’s country – and in that year’s Commonwealth Games he had won the team sprint with Hoy and MacLean. But Fred was most enamoured by Ross’s French heritage and his capacity for hard work.

At the academy, Ross had lowered his personal best for the 200m from 10.7 to 10.1 seconds. He had been a full-time rider before joining Fred but Ross had since grafted discipline onto his training. He told me it was important I showed the same application. I relished such seriousness. There would be no danger of me giving anything less than my very best to the academy.

Ross, in his laidback style, didn’t fuss over me. Later, when we went out together for a while, he admitted wryly that he might have done more to help me settle in Aigle. But Fred was charming and the regimented routine occupied most of our time. I soon learnt that, for example, we had to line up in a queue early every Wednesday so we could collect our clean sheets. We’d make our beds by 7am sharp.

Based in a hotel, which we shared with an international hotel school, the UCI cyclists lived in a series of rooms that stretched down a long corridor. The numbers fluctuated but, generally, there were between twelve and fifteen riders working under Fred. In contrast, almost two hundred students were registered on a course of hotel management and hospitality. We lived a different life to the aspiring hoteliers.

Every morning we caught a 7:30am train to our language lessons. We studied French while the other nationalities, including the Chinese girls, Li Na and Guo Shuang, were taught English. As we had to walk to the station, and did not dare miss the train, we set off early from the hotel, grabbing a quick breakfast on our way out. Snow had already fallen in November. I learnt quickly to rug up warmly, pull on my snow boots and make the slow trudge to the station. On the train we would vegetate for forty minutes, dozing or staring out of the window at the beautifully snowy landscape that flashed past in a blur.

At least Swiss French was spoken more slowly. I found it much simpler than ordinary French, which I had studied at school, and in the ninety-minute lessons our teachers concentrated on our conversational skills. I became braver the more I spoke in class. We were pushed hard to talk and I loved that rigorous cultural start to our day.

By 10 o’clock we were deep in a gruelling session of training, either on the track or in the gym. We were driven relentlessly and lunch came as some relief. The time-bound rituals then demanded that we would all take a communal sleep together after lunch. In the Salle de Repose, a large room in which Fred had ensured that mattresses were laid on the floor in the stark style of a Japanese dormitory, we were all expected to sleep like babies. I found it difficult when there were some loud snorers in the room and, even when I did fall asleep, I always felt terrible when we were woken at 2.30. It was like I had been shot with a tranquillizer gun. By 3pm, feeling jaded, we’d be back on our bikes. Each weekday was the same; and then every Saturday morning we all took a two-hour ride on the road.

Even here there were strict regulations. On the road you were only allowed to use the bottom three, smallest gears, irrespective of the speed of the group. I’d be pedalling flat out, knowing how much easier it would be if I could change gears. Fred, however, was usually around and he’d keep watch with regal scrutiny. Occasionally, at the back of the group, I’d sneak in a gear change just to taste the sweet relief.

My body was not accustomed to such intense training. It went into a state of shock during my first month in Aigle. I had never seen such big black bags under my eyes – which felt like they had sunk right into the back of my head. Luckily, we were allowed home for Christmas and I had a couple of weeks to recover.

Ross and I returned in early January. The snow lay thick on the ground and the cold up in the mountains began to bite. I worked hard and tried to keep warm as the temperatures dropped as low as minus 12. During training on the road, my face would be entirely covered as I huddled deeper into one of the red fleecy snoods Mum had knitted for me. It stretched over my nose while my eyes were hidden by shades that could not quite prevent ice crystals forming on my eyelashes. I also wore a thick headband and my helmet but, still, it felt as if the bitter cold had begun to eat away chunks of my face.

I felt anxious whenever we rode along the river and the path turned into a flat sheet of ice. We cycled in a straight line, in pairs, side-by-side, and we were fine as long as no-one braked or suddenly turned. Even a twitch of a wheel at the front could bring the whole pack of us down like a box of dominoes being spilled across the hard and clattering ice. Some of the Chinese cyclists were not as used to the road as me; and so I was always far happier when it was my turn at the front.

On the track, I struggled to match the pace of riders who were more accomplished and better drilled than me. Li and Guo were both incredibly strong. They were faster than me on the track and much more powerful in the gym. A few months earlier, at the World Championships, Li had won the keirin. Riding daily against a world champion, and having my times compared after every session to hers, was sobering.

I was used to training as a lone woman sprinter in Manchester but, in Aigle, I was surrounded. Apart from the Chinese girls, I raced against Canada’s Lori-Ann Muenzer, who had won two World Championship silver medals, and the American Jennie Reed, a recent World Cup bronze medallist.

Yvonne Hijgenaar was my age, twenty-two, but she was ahead of me. Apart from being the Dutch national sprint champion she had also reached the podium in the 500m at the previous summer’s European Championships – where I had ended up, instead, in the back of an ambulance. Hijgenaar was part of the Dutch squad that used Fred’s school as a training camp. Her compatriot, Theo Bos, had won three medals at those same championships and he strutted around Aigle with the certainty of a future multiple world champion. Teun Mulder, the third Dutch rider, had picked up a couple of medals at the Europeans and was also on his way to various future World Championship victories.

At different times there were riders from Belarus, Cuba, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Russia, South Africa and Venezuela and I loved the mix of cultures and personalities. I became close to three male cyclists: Josiah Ng from Malaysia, Tsubasa Kitatsuru from Japan and Chung Yun-Hee from South Korea. I always enjoyed it when they showed me their magazines of popular culture, aimed at guys in the Far East, and we soon developed our own private code as we adapted to the rigours of Fred’s serious regime. Fred had once told Tsubasa that he was ‘stupid, stupid, stupid!’ and so we resorted to saying things in triplicate. Someone would say, ‘Ah, Tsubasa … is so stupid, stupid, stupid!’ and we’d fall around amid much hilarity. And if someone was feeling emotionally or physically weary they would resort to a similar quip as they said, ‘Today, me no power! No power! No power!’ The boys were fun and interesting to be around and helped me feel a little less lonely.

I also had daily banter at lunch with the Frenchman behind the counter in the canteen. He regularly tried to trick me into eating rabbit or veal – even though I always reminded him that, for me, both were off limits, alongside horse meat. I enjoyed French cuisine but I was an ardent animal-lover.

He thought this was hysterical and would point to another deep and steaming dish. ‘Poulet,’ he’d say with a sly grin.

His chicken looked suspiciously like rabbit. ‘Lapin?’ I said.

He smiled mysteriously at me, and then shook his head.

‘Cheval?’ I asked more pointedly.

‘Non!’ he would exclaim innocently. ‘Poulet!’

Every lunchtime we had a similar conversation and I’d end up laughing alongside him and choosing a safer option – which I would then eat happily alongside my new friends at Fred’s school. I would often look around and feel fortunate to be in such a beautiful setting, with so many diverse professional riders in a cosmopolitan environment. I also thought Fred was great and I ate up the work he gave me with enthusiasm and, gradually, resilience.

I was motivated by a need to try and keep up with the other women. Every time we went out on the track our individual times would be logged in the book, and compared by the whole group that same day. There were no secrets. Everyone knew who was flying and who was battling. I was always at the back of the battlers, clinging on for dear life to the rest of them. It felt as if they were miles ahead of me. In the gym it was even more clear-cut. I could not lift the weights most of the women hoisted effortlessly.

My only advantage on the track lay in my superior leg-speed, while on the road I was more efficient and grittier during longer rides. All those years of chasing Dad had, at last, given me some benefit.

The months slipped past and I remained at the bottom of the timed track efforts. My lack of confidence was apparent. I was disappointed not to qualify in the sprint in my first two World Cups as an Aigle student riding in GB colours. Travelling full of hope from Switzerland, I would then arrive at a competition feeling suddenly weary and edgy. My qualifying times were never quite quick enough. I felt deflated; but the excellence of Fred’s coaching team and his managerial skills meant that I still savoured the training.

Gradually I could feel a new strength coursing through me, even if my results did not yet reflect that sense. Tangible proof only emerged during extended training races on the track. My slight build offered some reward here. I tired much less quickly than the bigger girls whose bulkier muscle-mass made them more subject to fatigue over distances exceeding 500m. Small victories in training provided reassurance that, slowly, I was moving forwards.

As late winter turned into a gorgeous spring in Switzerland, the daily routine barely shifted. But, deep inside the same pattern, I concentrated on developing my qualifying speed. My times on the track quickened. Something was stirring. I kept working.

The 2003 World Championships were held in Stuttgart that summer. I took a huge step forward, finishing fourth in the sprint behind the winner Svetlana Grankovskaya, Natallia Tsylinskaya and Mexico’s Nancy Contreras. Outside of the tight-knit training circle in Aigle, and my GB camp, everyone else in track cycling was astonished by my apparently sudden leap into the final four.

William Fotheringham, in the Guardian, was a more generous observer. Already looking ahead to the following summer’s Olympic Games in Athens, Fotheringham suggested, on Monday 4 August 2003, that ‘these World Championships, which finished yesterday, are merely the beginning, not an end in themselves … Perhaps the most encouraging portent for Athens was the surprise emergence of a world-class woman sprinter, Victoria Pendleton, who was narrowly beaten yesterday by Nancy Contreras in the ride-off for the bronze medal in only the fourth sprint series of her career. She has spent this year at the International Cycling Union’s track racing academy in Aigle, Switzerland, and has clearly proved an able pupil.’

More suspicious glances were shot my way, and dark mutterings were mouthed, by those who knew little of my work with Frédéric Magné. To them, the only answer for my improvement had to be found in doping. It didn’t bother me. The veiled innuendos told me how well I had done.

I had nothing to fear, being utterly clean, and so I peed cheerfully into every drug-tester’s little vial. I knew that none of the testers or the doubters had seen the journey I had taken over the last nine months.

They had not seen me rise from my bed early every morning. They had not seen me work hard as I tried my heart out against superior and more experienced riders like Li Na – who successfully defended her keirin world title. They had not seen me riding alongside Theo Bos in the build-up to him arriving in Stuttgart, where he won bronze in the kilo behind Arnaud Tournant of France and Chris Hoy.

Great Britain gained a second gold medal when Brad Wiggins swept to victory in the individual pursuit. The men won two more medals in the team pursuit and sprint events – and we finished fourth in the table. Russia were first, with four golds, but we had won one more than Australia and the Meares sisters who, for once, were not seen on the podium.

I smiled demurely when I handed my last warm specimen of urine to the waiting dope tester. If this was the kind of rigmarole foisted onto the world’s fourth-best sprinter, I could get used to it.

‘Danke schoen,’ I said in my very best Swiss-German accent.

My hard-won progress had been noted by Dave Brailsford and Shane Sutton. They knew Fred Magné was keen for me to stay on in Aigle for another year; and British cycling was prepared to fund an extended stay at a sprinting academy that might inspire me to a realistic tilt at an Olympic medal in Athens.