По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

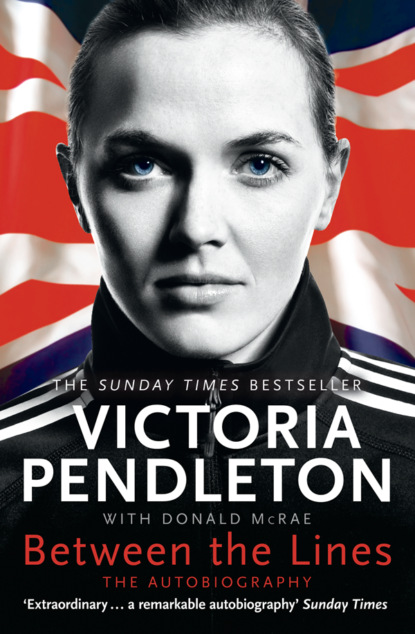

Between the Lines: My Autobiography

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I was still dazzled whenever I returned to the velodrome for training during my time away from university. I gazed in wonder at Chris Hoy and Jason Queally, trying to work out what they did to become such exceptional sprinters. Cycling has always been a masculine environment. I was used to the dominance of alpha males, especially with a dad like Max Pendleton, and riding against men as a junior. But Queally, Hoy, MacLean, Wiggins and the rest of the men’s elite squad were remarkable riders. I felt it was a sham for me to be training alongside them.

It was also odd for them. I think they were all slightly disconcerted and despairing of me. I would turn up to training in a GB top matched with a mini-skirt and sparkly sandals. The boys never said anything out loud to me but I did see the odd eye-roll and I could imagine them all saying, ‘Oh my gosh, this girl cannot be serious.’ But I was deadly serious. I wanted to get better and become more like them on my bike. The distinction, however, was obvious. I did not want to try and look like them or act like them off the bike. It felt essential that I should keep on looking like a girl, and acting like a girl, even as I tried to turn myself into a rigorously committed cyclist.

None of the men on the squad believed that competitive racing and femininity worked together. It was almost as if one concept automatically cancelled the other. I set out, in my own way, to prove that it really was possible to both be a very girly girl and an imposing cyclist. It was hard because, in cycling, I had no-one I could look towards. And only a few women athletes inspired me. Denise Lewis had won gold in the heptathlon at the Sydney Olympics and she was strikingly beautiful and graceful. She was a formidable athlete; and a gorgeous woman. I was neither; but Denise gave me the template to which I would aspire over the next decade. Grit and glamour did not have to be mutually exclusive.

At the velodrome I probably just seemed ridiculous. I had a very girly voice and a very girly laugh. I also appeared as a waif on my bike next to Chris Hoy – who had thighs almost as big as my torso and muscles that rippled with the explosive power a great sprinter needs. I was small and slight with thin legs and a small bum. It seemed unlikely I would find the force to generate a natural jump – the acceleration that distinguishes a good sprinter.

Yet all those Sunday mornings, chasing Dad’s wheel, had instilled conviction in me. I would not surrender easily. I might have appeared vulnerable but, deep inside, I was a fighter. I also knew that, when I concentrated my mind, I was capable of surprising people. I was not quite as delicate or as silly as some had decided. I was ready to shock a few cynics.

Martin Barras was top of my hit-list. In the midst of an eighteen-month stint at British Cycling in Manchester, Martin (or Mar-tain, to use the correct pronunciation of his name) took an instant dislike to me. ‘Miss Victoria,’ he said on the day we first met at the velodrome, ‘I’m going to find you very annoying …’

He might as well have slapped me in the face. Martin had never seen me ride my bike and we had not said more than ‘hello’ to each other when he declared his disdain for me. I was cut to the core and rendered speechless – a trait with which I’m not readily associated.

It soon became clear why Martin was so vehemently dismissive of me. He had specific ideas in regard to the physiological and psychological make-up of the ideal sprinter. I was far too puny, in Martin’s view, to generate any raw power. There was no beef or muscle on me – and Martin simply could not see where I would find the strength to overcome my physical frailty. He also took one look at me and decided I lacked the swagger and killer instinct of a supreme sprinter. Martin mistook my diffidence for weakness.

I don’t think he meant to be cruel. He just spoke with, in his opinion, blunt honesty. He could dismiss me physically but I was outraged he could deride my character within a minute of meeting me. Alongside my buried anger, I was shaken by his mockery. It made me wonder if he had seen some intrinsic flaw in me. All the confidence that had begun to flow through me since Marshall spotted me, and Peter Keen endorsed his belief, threatened to curdle over one snide sentence.

Privately, I resolved to prove Martin wrong. Yet, when training dipped or I was tired, I felt wounded all over again. I would have ridden well if I felt he respected or even liked me. But, to Martin, I was a source of pesky irritation. He set me back.

I summoned the courage to mention my problem to Chris Hoy and Craig MacLean – who both tried to reassure me that I had ‘got Martin all wrong’. Chris was convinced that Martin would be too professional not to give me a chance to prove myself. I nodded quietly, but Martin had made it plain that I would never become a decent sprinter. My only slim hope would be to switch to endurance events on the track.

Fortunately, Marshall, Peter and Heiko Salzwedel, the new German-born manager of the sprint squad, believed in me. In July 2001, and still only a twenty-year-old student, I was startled to be selected to ride for Great Britain in the European Championships. The team would be managed by Marshall and, as the Europeans were then limited to riders under the age of twenty-three, Olympic medallists like Queally, Hoy and McGregor were not included. I was still daunted that two of the three other members of the team had been on the Olympic podium less than a year earlier. Bradley Wiggins would race in the individual pursuit while Craig would triple up in the individual sprint, the 500m time trial and the omnium. Steve Cummings, another talented rider, would compete alongside Brad in the individual pursuit.

They were all much more accomplished competitors than me, and each of them was chasing victory in the Europeans as a win would secure automatic qualification for the World Championships in Antwerp later that year. Riding in the women’s sprint and 500m time trial I wasn’t thinking of winning anything. I was just hoping I wouldn’t fall off my bike and look a complete idiot.

The Europeans were held in the city of Brno, which we all pronounced Bruno, in the newly independent Czech Republic. I arrived at the airport in my GB tracksuit, brimming with pride and tripping over with nerves, while the boys managed to look outrageously laidback. I liked them all. Craig showed the first signs of interest in my future – in a way which would eventually help transform my approach to cycling – while Brad was the quirkiest guy in the national squad.

Brad was amusing and charismatic and I felt lucky to sit next to him on the flight across Europe. I also felt hopelessly out of my depth. Brad seemed to know everything about cycling while I knew nothing. He was intensely passionate about the sport, both on the road and the track, and he didn’t seem to mind that I was so ignorant. Brad answered my fascinated questions generously and enthusiastically. I was certain he was on his way to becoming a legendary cyclist – while it was more obvious than ever that I had fallen into a strange new world by pure chance.

When we arrived in Brno, I was in a room on my own and immediately felt disorientated. The boys teamed up naturally and, as the only girl, I was unintentionally sidelined while they met up to chat or watch a film. I sat alone in my room fretting about whether they’d said we would meet at 6.30 or 7.30 for a meal. So down I went to the hotel lobby at 6.25. When no-one appeared for twenty minutes I returned to my room – having worked out that they must have said 7.30.

I should have spoken to Marshall but I was worried about looking worried. I was soon paranoid about looking paranoid. The boys, of course, were all lovely when we did meet up for dinner and I calmed myself down. It was much better than sitting alone in my room, obsessing about the coming races.

There was little serenity in the Brno Velodrome. Whenever I saw another female sprinter I thought of Martin Barras. The women all had meaty thighs and big behinds. Their upper bodies were squat and powerful and their haircuts, for the most part, appeared equally severe. Mullets were still cool in sprint cycling. The Russian women, in particular, looked brutally strong. Martin would have loved to have exchanged me for one of them.

It soon emerged that my lack of physicality mattered far less than my hapless tactical knowledge. I realized how unprepared I was for the strategic minefield of the individual sprint. Unlike in the pursuit, where riders start at opposite ends of the track, two sprinters begin from the same point in a three-lap race. I was still learning the intricacies of the sprint.

Luck of the draw dictates which cyclist is drawn for the role of the lead-out rider – with the second sprinter having the potential advantage of, at high speed, expending less effort if they manage to use the draft behind the first rider to reduce the physical toll. On the last lap they can zip out of the trailing slipstream and, with gathering momentum, rocket past the lead-out rider. The element of surprise is vital to any attack.

Lead-out riders were far from helpless; even if the need to constantly look over their shoulders, to monitor the sprinter following them, suggested vulnerability. In their own way, the lead sprinter could dictate the slow pace of the first two laps and settle on the line of the ride. The first sprinter often will lead the trailing rider up the steep bank where they can pin them against the barrier and so force the second cyclist to overtake and assume the lead-out role. Some riders are brilliant at bringing their bikes to a complete halt on the curved bank by standing up and balancing with both feet motionless on the pedals and their front wheel at an angle. If they can hold this position, a ‘track stand’ or ‘standstill’, long enough, the second rider will be forced to start pedalling again and take over the lead role. But the first rider can also outwit his or her rival by accelerating earlier than expected and opening up a sufficiently wide margin to deny the second cyclist a chance to benefit from racing in the slipstream.

The old cliché of a cat toying with a mouse felt especially vivid and true as I watched the cruel psychology of the sprint in Brno. I definitely fell into the mouse-trap and my defeat was swift and almost merciful. There wasn’t even time for me to confront the tortuous tactical struggle. I got so confused in the slow ride around the track before the flying last lap and a half that I actually lost count. I even asked myself, at one bemused point, ‘Is this lap two or lap three?’ I was that bad.

I was finally classified a lowly eighth – both in the sprint and the 500m time trial. Unlike Bradley Wiggins, it did not seem like I was on my way to becoming a promising young maverick on the track. I just looked like a lost young girl, who hadn’t quite mastered the art of counting to three.

During my final year at university I reached an understanding with Phil Hayes, my tutor, and Marshall Thomas that I would spend one week out of every month training in Manchester. It would keep me in touch with the track as I tried to qualify for the Commonwealth Games in the summer of 2002. Supported by my university’s Elite Athlete programme, and by Sport Newcastle, I could just about afford my train tickets to and from Manchester.

I often struggled to Newcastle station, as I lived a kilometre away in the city, with the frame of my track bike over my shoulder, a wheel in one hand and my bag in the other. Taking my bike apart meant I wouldn’t be charged extra for it on the train – and I just had to worry about racing down the platform in Manchester shouting ‘’scuse me, ’scuse me, can I have my bike!’ as it would be stored in the far carriage. I always worried about losing it as, without a sponsor, I was responsible for all my own equipment. To that end I also supplied my own tools. As a way of reducing the weight, my dad had sawn down a spanner and made it so small the velodrome mechanics joked that it looked as if I worked on my wheels with a tea spoon. It was all part of my canny plan to travel light and cheap.

At Manchester Piccadilly I would walk another kilometre to the bus station. It sometimes felt like hard work, especially when it was cold and rainy, as I trudged down the road with my bike and heavy bag. I would then have to wait for a blue bus because it only charged 50p for a fare to Clayton. The two other different coloured buses cost £1.15 – and my saved 65p would go towards my tea that evening.

From Clayton it was only a short walk to the crack house on Ilk Street. We rather lovingly called it the ‘crack house’ because there was not much glamour or luxury about a place where you could stay for £10 a night. It belonged to the parents of Peter Jacques, a former sprint cyclist, and it was an open house for all cyclists affiliated to the national team. You could walk across the street and reach the velodrome through the back entrance, and for your ten quid you knew the house would be stocked with cereal, milk, butter and pasta. There was also a little corner shop where you could buy a jar of pesto or a loaf of bread.

The accommodation in Ilk Street was just as basic – as befitting one of only three houses on the road that had yet to be demolished. There were six bunk-beds in a large room and another all on its own in a very small room. I always opted for the small room. Sometimes the front door opened and a guy I had never seen before appeared. I couldn’t really ask if he was a cyclist because I wondered if I should have already recognized him. And, to make myself feel just a little safer at night, I would wedge a chair underneath the door handle in my bedroom at the back of the slightly scary crack house.

On 13 May 2002, I handed in my final assignment at the University of Northumbria. I was on course to graduate later that year with a 2:1 in my BSc Honours degree. My student life had flashed past in a sprinter’s blur. The following morning I left Newcastle for Manchester, to begin a journey that would consume the next ten years and three months of my life.

Martin Barras, much to my relief, had taken his leave of British Cycling and returned to Australia where I knew he would be much happier working with the strapping Meares sisters, Kerrie and Anna, than a lightweight girly like me. There would be further changes as Marshall Thomas was moving out of cycling and into photography. Peter Keen remained at the helm of British Cycling, at least for a short while longer. The introduction of lottery funding also enabled him to recruit Dave Brailsford, who had been a key adviser in obtaining that injection of public money, as the new programme director of British Cycling.

Dave was young and enthusiastic, with a degree in Sports Science just like me, and full of certainty that the country’s elite cyclists were just waiting to be galvanized. He believed in ‘the science of human excellence’ and in finding ways to allow riders to unleash the very best in themselves. Dave spoke in smooth sentences which sounded like they had been inspired by the books on management that he had read. In later years, words like ‘the aggregation of marginal gains’, which sounded so bizarre when you first heard them, would become seamless catchphrases that defined the attention to detail paid by the leaders of British Cycling. Dave and Peter were convinced that if every single facet of a cyclist’s performance was improved by even a couple of percentage points, the combined impact would transform the rider into a world-beating winner. It made such perfect sense that you wondered why no-one else had thought of it before Dave.

He carried the personal disappointment of not having achieved success as a road cyclist – and this just intensified Dave’s determination to succeed in a managerial role. Slowly, the evolution of British Cycling gathered pace. Further impetus was added by Manchester’s hosting of the 2002 Commonwealth Games.

I was selected to ride for England in the Games – my first senior international competition. Peter and Dave also confirmed I would be moved on from the England Potential Plan if I based myself in Manchester and committed myself to cycling. There would not be much money at first – but enough to pay for the monthly rent of a room and my living expenses while allowing a little pocket money. More significantly, I could train full-time and prepare myself for a life in professional cycling.

The Commonwealths were an unexpected prelude to those long-term plans. It was not the easiest of experiences as the only other girl I really knew on the British squad was Denise Hampson. At the Commonwealths she represented Wales and so Denise and I were in different parts of the village. I shared a room with an endurance rider I had barely met and always had the anxiety of looking for someone I could sit with in the food hall at every meal. Those little quirks unsettled me.

I was also shocked by the electrifying atmosphere inside the velodrome. As an unseeded rider, I was allocated the very first ride on the very first night of competition – in the 500m time trial. I could hardly believe it when I looked up from the pits, ten minutes before my bike was wheeled onto the track, and saw that the velodrome was crammed with enthusiastic spectators. The enormity of attention made my spindly legs feel just a little wobbly.

The arena went deadly silent when, supported upright on my lonely bike, I waited for the five-beep countdown. At the sound of the fifth and last beep, signalling the start of my timed race around two laps of the track, the velodrome erupted. The crowd had reacted before me and so, for a second, I remained static on my bike, stunned by the explosion of noise. I managed to start turning my legs just in time and, as I sped around the wooden boards, the roar of the crowd surged through me. The noise seemed to invade my very being. After I crossed the line, and looked down at my wrists as I circled the track in a warm-down lap, I could see that little goosebumps had formed on my skin.

I finished fifth in the time trial, missing a medal, but I was confused once more in the sprint. The tactical vagaries were as mysterious as ever – especially as I had never ridden the event on the velodrome’s 250m of shimmering pine. Struggling again to keep count of the strategically slow laps, I won my first heat against Melanie Szubrycht, my England team-mate from Sheffield, but I was still immersed in the tactical head-fuck of trying not to be outwitted by my opponent. In the semi-final, Kerrie Meares, of Australia, introduced me to the rougher end of professional cycling. I didn’t expect to beat her, but I thought I’d give Kerrie a little run for the line. But she went out of her way to intimidate me.

Even though she knew she had much more power and speed, she took me right up the bank and used her bike to flick me against the barrier. The crowd booed Meares vociferously. Even the briefest of glances made it plain that, comparing Meares’s physique to mine, she had the clear beating of me if we raced in a straight line. It seemed bizarre that she should feel the need to intimidate me.

It was illuminating to watch the final between Meares and Canada’s Lori-Ann Muenzer. ‘Suddenly the Friendly Games were wearing a scowl,’ Eddie Butler wrote in the Observer as he moonlighted from commentating and writing about rugby to cover an obscure sport like cycling. ‘Meares won the first of three sprints, but was disqualified for what the judges called “intending to cause her opponent to slow down”. In other words, it seemed to this novice spectator, she tried to drive poor Lori-Ann up and over the cliff of the north curve. And what’s more, she seemed to do exactly the same thing in the second leg. The crowd was just building up to a growl of disapproval when a judge fired a gun twice. Presumably this was to halt the race, but in terms of keeping the atmosphere wholesome it was most effective, if slightly draconian. Meares was not disqualified this time, which seemed a bit iffy to me, but it did not cause a flutter among more knowledgeable onlookers. They restarted leg two, which Meares won in legit style. As she did the decider. All very thrilling; she won by half a spoke on the line.’

I could see how the brutal riding and bullish physique of the Meares sisters, Kerrie and Anna, chimed with the perspective of their new coach. Australia, the Meares girls and Martin Barras were dominant. But the British squad, split into four countries at the Commonwealth Games, was growing stronger by the month. I already knew that, for Chris Hoy and Bradley Wiggins, a glittering future loomed. My own life, both on and off the bike, was less certain.

It took just weeks for the next twist. I was invited to race for Great Britain in my first World Cup event in Kunming, China. Even the name, Kunming, sounded deeply mysterious in early August 2002. Mum drove me to the airport and we met Shane Sutton for the first time. I found him a little frightening, and Mum admitted later that she felt mildly concerned leaving me in the company of such an intense Australian.

Shane had won a gold medal alongside his brother Gary in the team pursuit at the 1978 Commonwealth Games, and he’d eventually moved to Britain in 1984 to continue racing. Three years later, he had ridden the Tour de France. Since his retirement he had become the national track cycling coach in Wales and, in 2002, Shane had joined the GB programme. We were both new to the squad but there was little doubt that the grizzled Aussie was coping better than me.

Shane must have recognized my uncertainty, for he did much to try and help me settle. Beneath the gruff exterior there was, clearly, a paternal streak in him towards me. I was overwhelmed. Soon after we touched down, and feeling dazzled after so many hours in the air, I was shocked by a different culture. Walking to the airport toilet I sidestepped a few phlegm-ridden tracers of spit as old women simply cleared their throats and shot the snotty contents onto the concourse floor. I was even more taken aback by the sight of women leaving their toilet doors wide open as they did their personal business over an open hole. Feeling very prim and proper, I closed the door to my own cubicle. I was not quite ready to embrace all the customs of Chinese culture.

Our hotel, however, was beautiful, with huge ornamental gardens where hedges were shaped into Chinese dragons. I was even more fascinated by the contrast that was evident from the back window of my lavish room. In the slum behind the hotel, lines of corrugated iron and tarpaulin could not hide the seething life as people washed their hair, squabbled and shouted while children went to the loo in full view on the side of the jumbled streets.

Kunming was the capital of Yunnan province and the track was a two-hour drive away from the city. In a crammed minibus, Bradley Wiggins, Tony Gibb, Kieran Page, Shane and I sat alongside riders from other countries. I usually perched next to a slightly older and kind Czech sprint cyclist, Pavel Buran. My eyes must have looked huge as I gazed at everything around us. We had already been offered suckling pig at a welcome banquet at our hotel, which I firmly declined, but I was still shocked to see two half-pigs stuck on a spike on the back of a motorbike. A couple of kids were perched upfront on the bike, with their dad behind them, and I thought they would have been amazed to hear that, when I was a girl, I loved pigs so much that my pencil case at school was covered in pictures of them. I was not quite ready to see so many butchered animals covered by flies as they flashed past our bus.

Once we had escaped the clogged heart of Kunming we hit some bumpy road which took us deep into rural China. Women and elderly men could be seen on the land, doing the work of farm machinery with their hands, as we raced through the dust and the heat towards my first World Cup event.

The brand new outdoor track, found at the base of the Himalayas, was hidden behind a big cast-iron gate which swung open slowly to reveal a mysterious sight. It was the first time I had seen a 330m track. We mostly raced at night, so it looked even more surreal under floodlights as giant moths flew around our heads. They were around two inches in length, and half-an-inch wide, and they looked scary – especially when their furry wingspan spread to three inches. I did my best to duck under them and also to avoid riding over the splattered remnants of squashed moth on the track.

Li Na, from China, won the women’s sprint. I finished fifth – amazed to have completed my first World Cup. I also felt like a freak-show star for, along with a blonde German cyclist, Christine Müller, I was stopped continually by Chinese people who wanted to take a photograph. Christine and I looked as unusual to the rural Chinese as the teeming slums and spiked pigs had seemed to me.

Shane Sutton still watched over me and, on the long trip home, we stopped off in transit in Bangkok. It was a nine-hour wait and Shane arranged for all of us to take a tour of the city. In a night market in downtown Bangkok, eating ravenously while watching some sumptuous Thai dancing, I melted into another experience. If these were the kind of strange, new places where cycling could take me I was ready for so much more. I was ready to see the world.

(#ulink_dd116033-e56f-510c-aa1c-62811bfdfea5)