По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

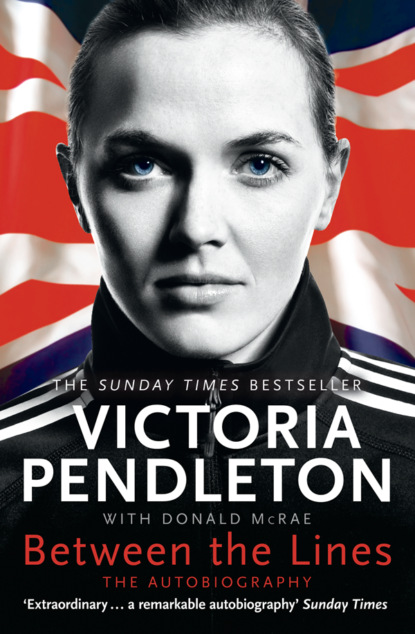

Between the Lines: My Autobiography

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

If it was difficult for me to think of myself as a potential podium cyclist, Peter Keen, who would soon become performance director at UK Sport, was emphatic about my prospects. I could hardly believe his words when, on the second last day of the year, my mum pressed an article into my hands. It was from the Guardian, on 30 December 2003, in an article headlined:

Young, gifted and on track to make headlines in the coming year: Coaches and experts from 12 sports name their top tips to make a breakthrough in 2004.

The chosen dozen included the cricketers Alastair Cook and Ravi Bopara, the gymnast Beth Tweedle and the footballer Andy Reid. Graham Saville, described as England’s youth guru and a member of the Essex County Cricket Club committee, considered the credentials of Cook who, then, was only eighteen: ‘Cooky scored a fifty in each of his first three matches for our first team. He’s a talented cricketer and I’m told he was a very good singer – a leading chorister at St Paul’s cathedral, apparently, until his voice broke.’

Lewis Hamilton was the penultimate name on the list of twelve. He was nominated by Martin Whitmarsh, the Managing Director of McLaren, who wrote of his ‘unusual talent’.

I was last on the list. Reading the words, I had tears in my eyes, hardly daring to believe that anyone could show such faith in my future:

Peter Keen, British Olympic coach: ‘Victoria Pendleton is the fastest emerging British cyclist in my book, with another sprinter, the Scot Ross Edgar, not far behind. She is 23 and will be pitching for a medal in the women’s sprint and 500m time trial. She was fourth and seventh in those events in the World Championships, but her rate of improvement is so fast and the gaps are so tight that if she goes 0.2 seconds faster it starts to look interesting. Vicky is bright, learns quickly and has natural speed and power that have only come through since she’s put in the strength training. Superficially she looks fragile, but she’s incredibly determined. She’s a complete sprinter now, and 2004 could be her year.’

It’s hard to tell how I got from there to here. I’m sitting on my bed, in my bare room, down an anonymous corridor at the hotel in Aigle, Switzerland, which doubles as the base for Frédéric Magné’s and the International Cycling Union’s racing academy. There is a Swiss Army knife on the white pillow. It has a bright red grip and two sharp blades of differing lengths. It also contains, at the flick of a wrist, a corkscrew, a can opener, a wire stripper, a key-ring, tweezers and a small pair of shiny scissors. The longest blade fills my gaze. I have been here before. I know what I need to do to make a new pain which will feel more clean and honest than the knotted mess inside me.

This year, 2004, has not been easy. It has been confusing and distressing. There have been a few uplifting moments. I won my first World Cup, in the individual sprint in Manchester in April. But there was also frustration. My Manchester victory was meant to be the perfect launch for a big breakthrough in the World Championships in Melbourne the following month. I qualified eighth fastest and then beat Yvonne Hijgenaar in the first round, Clara Sanchez, the French rider, next, before, in the quarter-finals, defeating Tsylinskaya, who had won the World title two years before. In the semi-final I faced the defending champion from Russia – Grankovskaya. It was a disaster. Adjudged to have crossed the line, and moved out of my designated racing area into Grankovskaya’s lane, I was relegated from the race and consigned to a scrap for the bronze medal.

As my mood dipped, so my desire wavered. I lost both third-place races to Lori-Ann Muenzer – who I knew so well from Fred’s academy. Lori-Ann had turned thirty-eight the week before and I felt dispirited that I had lost a World Championship medal to a rider who was fifteen years older than me. Even worse than that, when we shook hands on our bikes soon after crossing the finish line, Lori-Ann held mine and, with a smile, said: ‘You will always be a princess – but you will never be queen.’

From the stands people would have only seen her smiling at me as we completed our warm-down lap. In calling me ‘a princess’, she seemed to be implying that I was spoilt and pampered. I knew that she received no support from her academy in Canada while British Cycling paid for my entire stay in Aigle. But there was something else in her barbed comment. I felt Lori-Ann looked down on my kind of femininity. She had short and spiky blonde hair, with lots of piercings, and she was assertive and relatively intimidating. I had tried initially to befriend her but I found her closed and even cold towards me. Our relationship had not improved whenever I rode much more quickly than her up the mountains – as the climbing suited my smaller frame. Yet I was still shocked and even distressed by her taunting of me as a princess on the track.

After eighteen months of training under Fred I did not seem to be making the progress I should have done. In my depressed mood I considered fourth place at the Worlds a failure – as it repeated the same finish from the previous year in Stuttgart.

Grankovskaya defeated Anna Meares in a close final, by two races to one, but the younger Australian was a clear star in Melbourne. Her sister, Kerrie, was still out of competition with a back injury but Anna, just three days shy of being exactly three years younger than me, followed silver in the sprint with gold in the 500m time trial. I finished a lowly ninth. I was losing to riders both older and younger than me. It was hard to ignore the beaming joy of Martin Barras and the happy tears of the Meares sisters.

‘I’m ecstatic,’ Anna told the press corps after she had completed a lap of honour, draped in the Australian flag and acclaimed by tumultuous applause. ‘I probably didn’t expect a result like this. I thought it would be another year or two away. But Martin changed my training programme in the lead-up. We went back to the basic building blocks then trained me up for this. But I can’t tell you what we did. That’s a secret.’

I didn’t really care about the secret training routine of Anna Meares and Martin Barras. I just wanted to get the hell out of Melbourne and back to Aigle where, I hoped, Fred Magné would lift me out of my fourth-placed rut. I wanted to be like Chris Hoy, who had again won the kilo at the Worlds, or Theo Bos, the men’s new world sprint champion. I needed Fred to galvanize me.

Fred was cool and charismatic. He was also friendly towards me but, increasingly, I noticed how different he was around Ross. ‘Oh,’ Fred always laughed, ‘Ross is my favourite.’

I also loved Ross. He was great. But, secretly, I envied the relationship he had with Fred. They were able to kid around, and make each other laugh. Even more significantly, Fred went out of his way to boost Ross and to make him realize how much he had progressed. I wished Fred could believe in me as much as he believed in Ross. I knew I was being petty and so I never said a word to anyone. I just pedalled away, silently, hoping that one day I would be good enough to be called Fred’s favourite. I was so insecure and vulnerable, and in such desperate need of being liked, that those confusing thoughts tightened inside me.

Logically, disappointment at remaining in fourth place in successive World Championships was a healthy sign of my raised expectations. But the pride I had felt in Copenhagen and Stuttgart, at my first two World Championships, had soured in Melbourne. I felt stuck – and emotionally blocked.

My problems had started months before Melbourne. I guess they really began when, early in 2004, I resolved to prove to Fred that I was worthy of his highest praise. It seemed to me that, unlike most of my rivals, I lacked core strength. I had studied core stability at university and thought I’d include some additional abdominal exercises in the gym. Determined to pull myself up from the same static level and, having a degree in Sports Science, I considered myself sufficiently qualified to decide whether another set of work on my abs would be of benefit.

However, as I soon learnt, the regimented order of Fred’s training programmes meant that any deviation or change was discouraged. Someone told Fred. They dobbed me in – as I might have said if I was still a teenage schoolgirl. Fred called me into his office. ‘What’s the matter with the programme I give you?’ he asked angrily.

‘Nothing,’ I said. ‘I just thought I was being proactive …’

‘No,’ Fred said cuttingly. ‘You’re being disrespectful to the programme – and to me.’

‘I’m really sorry,’ I said. ‘I should have asked for your permission.’

‘You should respect me more …’ Fred said coldly.

I was mortified. My respect for Fred ran so deep that I ached for his approval. I could not believe that, instead, I had unleashed his disdain. In a recurring theme of my youth I had always feared letting down figures of authority, my dad most of all, and so I felt diminished by disappointing Fred.

Later that week, at the end of a hard training phase, I was literally blowing after a morning on the track. I felt finished. That sense of deep fatigue disturbed me. I needed to work still harder. So the next morning, I added another ten minutes on the rollers before breakfast. I thought my body needed it; and it was just a way of getting a sweat on before the day’s real work began.

Again, someone chose to report me to Fred. I was called once more into his office and, this time, he tore strips off me. I had never been chastised so severely. Dad might have used his silent treatment on me, when I was a girl, but this was different. Fred ripped into me.

‘Not only did you do this once,’ he said furiously. ‘You did it twice. I cannot believe you would do this again!’

‘I’m so sorry,’ I said in a familiar echo. ‘I’m just not thinking straight.’

Fred was unrelenting and I felt terrible. Our relationship deteriorated from that point. He doubted my integrity. How come, he seemed to ask every time I spoke to him, I was the only person at the academy who felt the need to disregard a programme he had planned so methodically? My apologies could not change anything. It felt as if something had broken between us.

I spent many hours in my room, alone, feeling an outcast. Castigating myself for letting down Fred, I questioned my own worth. It got worse. I cried to myself and became still more withdrawn. The hurt inside me was like a raw wound. I needed to take my mind away from such a dark place.

At first I just stuck my fingernails into the skin of my palms. It was not enough. I needed the next step. I felt like hitting myself. I was that low and stupid. I wanted to bruise myself as a kind of penance. I know men sometimes punch walls in frustration. They even crack their skull against the bricks to draw blood. It’s violent and it’s angry but it offers some kind of release.

I didn’t feel violent or angry. I just felt desperately sad and unworthy. I felt the urge to mark myself.

The first time, before Melbourne, I used the knife almost thoughtlessly. I did not sit down and decide, consciously, to cut myself. It was almost as if, instead, I slipped into a trance. I held the Swiss Army knife in my right hand, feeling the solid weight, as if it promised something beyond the empty ache inside me.

A shiny blade traced a faint line on the pale skin of my left arm. It didn’t hurt, as I had yet to add any pressure. The slight indentation was at least three inches above my wrist. I had no wish to cause myself lasting damage; and there was no thought of me using the knife to open up the blue veins in my wrists.

I did not want to kill myself. I just wanted to feel something different.

Pressing down harder I had a sudden urge to make myself bleed.

The cut, when it came, did not really hurt. It was a sharp and clean sensation. I only drew a little breath at the sight of a thin line of blood. It was a tracer of my shame. After staring at the cut for perhaps a minute, seeing how it opened just a little wider as the blood trickled from the sliced gash, I cut myself again. I pressed harder and deeper and, this time, I felt it more plainly.

My skin opened up like a peach. The blood looked very red. It flowed more quickly.

I felt calm. It was not a bad cut and the bleeding soon stopped, taking away some of the pain inside. My arm stung a little but, mostly, numbness spread through me.

The next morning, waking early for training, I looked down at the red lines running down my arm. One looked much angrier than the other but, as I pulled on a long-sleeve top to hide the scars, I could not really regret what I had done. It had happened and, for a while, it had helped. I put it out of my mind.

It happened again, and again, and each time the same soothing numbness spread through me.

So here I am, once more, post-Melbourne, reaching for the same Swiss Army knife. I hold it in my hand. It carries the usual comforting weight. I look around me. The walls in my room are white and clinical – and very different to the redness of the cutting. I think of the gorgeous scenery outside. I know how lucky I am. I am living and working in a place of remarkable beauty. Other people are paying for me to ride a bike around in endless circles. I am fortunate. I love the training. The pain of pushing myself hard satisfies me. I relish the gruelling work.

Knowing how lucky I am, that my problems are so trivial compared to the trauma that people all around the world face every day, I feel ashamed. I don’t want to be weak. I don’t want to be self-indulgent.

I know the truth. I am not starving. I am not in a war zone. I am not being tortured. I am free from persecution and injustice. I am a white, middle-class twenty-three-year-old English girl from the Home Counties. I am in the midst of an opportunity of a lifetime. What right do I have to feel so bereft?

The question goes round my head as if, like me, it’s riding a bike in circles on a wooden track.

I think of Fred, and his disappointment in me, his certainty that I no longer respect him. I feel, again, worthless and useless.

In my bad moments I have sometimes managed to ward off the need to cut myself. I turn to a cutting instead, with Peter Keen choosing me as his sporting figure to watch in 2004. I keep it in a slim plastic wallet. Now, trying to be rational, I put the knife down. I hold the plastic wallet in my hands and, through the shiny surface, I re-read some of Peter’s words about me:

Vicky is bright, learns quickly and has natural speed and power that have only come through since she’s put in the strength training. Superficially she looks fragile, but she’s incredibly determined. She’s a complete sprinter now, and 2004 could be her year.

I am determined. I know it. I’ve been determined since those early Sunday mornings when, chasing Dad up a hill, I pedalled hard until it felt like my heart would burst. I never lost sight of Dad. But I not only look fragile. I am fragile. I feel as if I could crack and splinter into hundreds of pieces.

Peter Keen’s sentences blur beneath the plastic. I don’t feel bright or speedy or powerful or strong. I don’t feel like a complete sprinter. I feel like a wreck. I feel like a waste of space.