По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

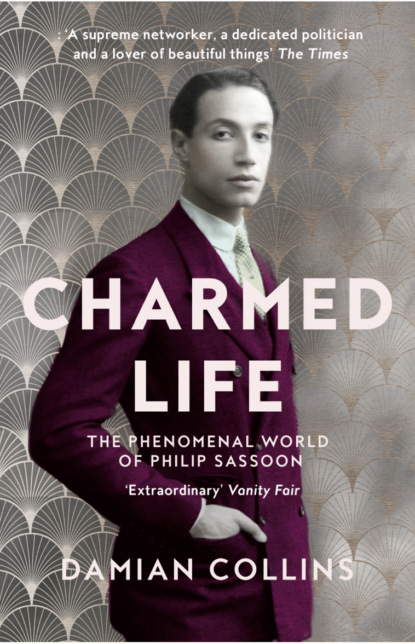

Charmed Life: The Phenomenal World of Philip Sassoon

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

His aeroplanes carried his adopted symbol of the cobra. A bronze statue of a coiled cobra, rising to strike, also decorated the bonnet of his Rolls-Royce motor cars, in place of the flying lady known as the Spirit of Ecstasy. In ancient Egypt the cobra offered protection to the pharaohs, and in eastern mythology symbolized good fortune, new life and regeneration – the serpent could change its skin and each time emerge new and whole. Now that he was out of his khaki uniform, 1919 would be a year of regeneration for Philip Sassoon; he had just turned thirty, with seemingly limitless funds at his disposal, no personal ties and a seat in the House of Commons.

Harold Macmillan, another Eton and Oxford survivor of the war, remembered, ‘To a young man … with all the quick mental and moral recovery of which youth is capable, life at the end of 1918 seemed to offer an attractive, not to say exciting, prospect.’

Looking back on this period, Evelyn Waugh wrote, ‘Everyone was agog for youth – young bishops, young headmasters, young professors, young poets, young advertising managers. It was all very nice and of course they deserved it.’

As a surviving member of the lost generation, Philip Sassoon was also determined to make the most of the life given to him but denied to so many of his friends by the war. The strictures of Edwardian society had been replaced by new social freedoms. People had grown used to mixing freely with people of all ranks and stations in life during the war, and women in particular now had much more independence. Philip would not subscribe to the view first expressed by the American writer Gertrude Stein that the lost generation were not the young men who had been killed in the war, but those who had returned to a life of drink, drugs and directionlessness.

Philip’s life was driven by energy and purpose, and he would become one of those singular young men who suddenly rose to prominence both as a society host and as a politician.

In March and April 1919, Philip marked his new freedom from the army with a holiday in Spain and Morocco, accompanied by a fellow staff officer from GHQ named Jack. Together they experienced the cultural treasures of these two countries and Philip was particularly moved by the works of Velázquez

at the Prado museum in Madrid. In his travel journal he declared Velázquez to be ‘the most wonderful artist in the world. Best of all is the “Las Meninas” [Maids of Honour]. If by a miracle we mean an event in which the effect is beyond measure out of proportion with the seeming simplicity of the cause, then we may say that of all the great pictures of the world this may most precisely be called miraculous.’

Philip Sassoon was not alone in his regard for Las Meninas. His friend William Orpen later wrote, ‘It is hard to conceive of a more beautiful piece of painting than this – so free and yet firm and so revealing … Like all of the great artists Velázquez takes something out of life and sets it free.’

Las Meninas had also been an inspiration for the composition of works by John Singer Sargent, and Sir John Lavery’s 1913 portrait of King George V and his family.

Las Meninas has been a mystery to the centuries of admirers who have stood before it. The scene is set in the Alcazar Palace in Madrid, and the central figure is the five-year-old daughter of King Philip IV of Spain, the ‘Infanta’ Margaret Theresa. She is accompanied by her two maids of honour, her dog, and two court dwarfs, Maribarbola and Nicolasito. To the left of this group stands Velázquez himself, looking towards us as he works at a large canvas, but we cannot see what he is painting. Facing us on the far wall in the picture is a mirror reflecting back the shadowy images of King Philip IV and Queen Mariana, suggesting that they might have been standing next to the viewer. Next to the mirror is an open door, and through it stands a nobleman, perhaps arriving with news for the King.

The art historian Kenneth Clark wrote of the painting that ‘Our first feeling is of being there.’

It not only transports you back to the court of Philip IV of Spain, but invites you to look at it through his eyes. For Philip Sassoon, standing before Las Meninas inMarch 1919, after the fall of the Emperors of Austria, Germany and Russia, he might have considered the precarious position of rulers, and how quickly they can pass from being the centre of attention to becoming peripheral figures, like the king in the painting. Looking at the beautiful but vulnerable Infanta, Philip might have also reflected on his own gilded childhood at the Avenue de Marigny, in that lost pre-war world of Paris in the time of his parents and grandparents.

On his tour of Spain, Philip was greatly impressed with the Alhambra, the palace and fortress complex in Granada. It provided ‘a lot of ideas for Lympne … The Alhambra … must remain for all time the crowning glory, the seal, the apogee, in a word the supreme consummation of Moorish Art.’

It was a timely inspiration, as back in England Philip Sassoon’s great project in 1919 was the completion of his house and estate in Kent. Port Lympne was more than just a building project designed to provide him with a comfortable home in his constituency; it was a work of art in its own right and a statement of Philip’s flair, style and ambition.

His friend the writer Osbert Sitwell thought that Lympne captured his ‘fire and brilliance as a young man’.

Sybil also recalled that Philip ‘loved [Lympne] very much because he had built it himself’.

Sir Herbert Baker had designed and built the mansion before the war, but was unavailable to continue the project as he was working with Sir Edwin Lutyens in India on the construction of New Delhi. Instead Philip brought in the fashionable young architect Philip Tilden to complete the interior and external works on the estate. Tilden is now better known for his work for Winston Churchill at Chartwell, but Philip Sassoon was his main patron in the early 1920s; and it was he who introduced Churchill to Tilden when Winston was in the process of purchasing his Kent estate. Sassoon and Tilden were kindred spirits – dynamic and creative, of similar age and shared artistic tastes. There was also a strong mutual respect: Tilden thought that no more ‘brilliant man existed for this age than Philip. I do not mean necessarily brilliant in scholarship, but in effect; intensely amusing and amused, full of knowledge concerning many things that others care not two pence for; imaginative, curious and above all intelligent to the last degree.’

Tilden believed that Port Lympne should be ‘all new and forceful, pulsing with the vitality of new blood’.

Everything inside the mansion house would be entirely modern. Philip didn’t bring any of the antique furniture or artworks from his other homes to Lympne; nearly all of the contents were commissioned from contemporary artists and designers. The Country Life profile of Lympne exclaimed that ‘to be blasé has become a pose, almost an accepted virtue. Today most of us think, some of us even like to think, that we are prepared for everything – at least nearly everything. For everything except say a visit to Port Lympne … there it is possible to feel some inkling of true wonder.’

Philip had learnt at Eton the importance of external conformity in behaviour, whatever the true nature of the emotions that lie within, and the same principle was applied to Lympne. The mansion was a modern building, but made to look more established by being built from old bricks. As you approached the entrance to the house from the east, it presented the stylish yet conservative appearance of an old English manor. Philip also bought old garden statues from the country house sale at Stowe to add to the impression of the property’s longevity.

Yet from the south side Port Lympne had an Italianate feel, with curved loggias extending from the house and a series of terraces below. As a final external feature Tilden created a great stone staircase to the west of the house which climbed the slope to the rear, seemingly rising like Jacob’s ladder to infinity. The staircase was decorated with fountains and pavilions supported by classical pillars, an homage to Lympne’s ancient heritage as a Roman port. It provided a sense of drama and ambition more akin to the golden age of Hollywood than to the Home Counties of England.

The greatest transformation came once you had crossed the threshold. As you went through the green bronze front door, you were transported into what Marie Belloc Lowndes called ‘a strange and beautiful house – a house which might have come right out of the pages of Hajji Baba of Ispahan’.

,

The oriental appearance of the interior gave free rein to Philip Sassoon’s more exotic creative ambitions and was completed at seemingly limitless expense. The drawing room had given him particular trouble. Just before the war, while watching the Josephslegende ballet, choreographed by Nijinsky for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, Philip had fallen in love with the sets designed by the Catalan artist Josep Maria Sert.

He commissioned Sert to paint a mural for the drawing room at Lympne, and the artist created a work which was an allegorical depiction of Germany’s defeat in the war. France was shown as a draped and crouching female figure being attacked by two German eagles. She was assisted by a flock of children representing the Allies, each wearing a headpiece from their national costume. The Indian Empire was portrayed by elephants which were shown on the broad breast of the fireplace in the centre of the room carrying all before them. The story ends with the German eagle being torn asunder, feathers flying.

At that time Sert favoured painting in a monochrome style, but at Lympne he used tones of black and gold, rather than black and white, which while impressive were somewhat overbearing in the drawing room. Philip came to have grave doubts about Sert’s work. ‘Personally I think it monstrous,’ he wrote to his friend Sir Louis Mallet, adding that the work was

Of course ingenious in imagination and drawing – but so frightfully heavy that although the room is beautifully proportioned you feel impelled to throw yourself down on your belly and worm yourself through the door as the only alternative to battering out one’s brains against the ceiling – and from being a light sunny room brighter than the inside of an Osram bulb it is now so pitchy that you have to whip out a pocket electric torch even at midday or you’re as good as lost. And an awful cooked celery colour which gives you a liver attack before you can say knife. Unless Sert can alter it past all recognition it will have to go.

In an attempt to salvage the situation Philip asked John Singer Sargent’s advice on how to complete the room. Sargent’s only comment on being introduced to Sert’s work was that the remaining uncovered walls should be ‘slabbed with marble the colour of chow’. Philip Tilden, who was given the task of executing the command, recalled that ‘this remark was typical for Sargent; he was never a man of many words, and no doubt we should have known what he meant. But there are many chow coloured dogs of many colours, and a whole day’s argument could not elucidate his meaning.’ By a process of elimination they settled on a warm, moss-brown marble, streaked with gold, which had to be created synthetically by a firm at the back of Marylebone Station in London.

The drawing room was connected to a small library which looked over the terrace and out to the sea beyond. From the dark brooding colours of Sert’s room you were transported to a bright space with books lining the walls, all bound in a pinkish-red morocco leather and housed in wooden bookcases sheened with ‘gilver’ – silver with a tinge of gilt. The carpet was green and pink, with pink also used in the lining of the bookshelves and in the marble of the mantelpiece. Passing through the library you arrived in the dining room, with its walls lined with marble-effect lapis lazuli, producing an undulating and moving cover of cobalt blue. Set against this were golden chairs around the central table, with arms carved to resemble the wings of an eagle. The artist Glyn Philpot created a frieze depicting a scene from ancient Egypt of near-naked black men, described by Philip Tilden as ‘gesticulating and attitudinising figures’,

working with animals.

Looking back from the dining room, through the doors into the library and then on to the drawing room, you could enjoy the contrast of colours, tones and textures – the cobalt blue of the lapis lazuli giving way to the red, gold and pink of the library and leading to the brooding gold, black and mossy tones of the drawing room.

The most talked-about feature of the internal works was the creation of a Moorish patio in a courtyard at the centre of the mansion buildings, perhaps inspired by Sassoon’s visit to the Alhambra Palace. It was to be accessed from the first half-landing of the main staircase at the centre of the house through a sliding plate-glass electric door. The structure included white marble columns, white-stuccoed walls and brilliant green pantiles. The courtyard was decorated with fountains and running streams, orange trees and cypress hedges, and behind columns at the far end of the patio were two free-standing pink marble baths in an area that had the appearance of a Turkish hammam. The overall scene was reminiscent of Sir John Lavery’s painting of a Moorish harem, and was most certainly the feature of Port Lympne that Lady Honor Channon, the wife of Chips Channon, was referring to when she compared the house to a Spanish brothel.

Port Lympne was not a place for sitting around; the interior stimulated rather than relaxed its guests. For this reason Philip Tilden added an additional library standing to the right of the main entrance to the mansion. It was a domed octagonal room, modelled on the Radcliffe Camera at Oxford, and designed to be a sanctuary from the rest of the house. Philip Sassoon’s private quarters were on the ground floor adjoining the front terrace, and his restless pace would dictate the rhythm of life at Lympne. He would go running in the grounds in the morning, and there were two tennis courts set at right angles to each other, so that as the sun moved through the sky you could still play without it being in your eyes. Tilden also designed a large marble swimming pool which was built below the terrace. The pool comprised three square sections making one rectangular-shaped bathing area. A fountain in the central pool required its own water supply after it was discovered that when fully operational it drained the resources for the whole area; a wave machine had also been built for the pool. Eventually they found that the weight of the marble pool was too great and it was in danger of sinking into the garden below, which led to it being redesigned around the single central pool which remains to this day.

Lympne was for entertaining, and particularly for summer parties. Philip wanted it to be a place, as Taplow Court had been for Lady Desborough, where his friends would choose to gather. The estate would also be a home to his small court of close friends who since the war had become like an extended family to him. In addition to Tilden, who was in semi-permanent residence while the works on the estate were completed, there was Sir Louis Mallet,

who had rented a house from Philip on the edge of the estate called Bellevue. Sir Louis was a bachelor and retired diplomat who had been close to Philip’s parents and in their absence took on a mentoring role, somewhat similar to the relationship that Philip had enjoyed with Lord Esher during the war. Louis had sold his own home at Otham in Kent to move to Lympne, an act that Philip Tilden referred to as a ‘capitulation to Philip Sassoon’s selfishness’. Tilden said that he did not mean this in an unkind sense, but as an expression of ‘the fact that Philip needed someone of experience near him as a dumping ground for confidences’.

Louis also kept rooms at 25 Park Lane when he was in London. Other frequent guests included older friends like Marie Belloc Lowndes and Alice Dudeney, as well as his cousin David Gubbay, who had taken over the running of the London office of David Sassoon & Co., and his wife Hannah. Alice Dudeney recorded her first visit to Lympne in the summer of 1919 in her diary: ‘The house most lovely and luxurious. I seem to be staying with a fairy prince. While I was in my bath before dressing for dinner he came knocking at the door. “Mrs Dudeney, are you in your bath? Get dressed and come down quick. I am dying to see you.” All very boyish and gay and much emphasised.’

The estate was also conveniently located, less than 70 miles from London and close to the Channel ports, and Philip particularly encouraged friends to stay when on their way to or from the continent. Duff Cooper, a contemporary of Philip’s at Eton, and his wife Diana spent the first two nights of their honeymoon at Port Lympne before continuing their journey to France. Patrick Shaw Stewart had been Duff’s rival for Diana’s affections before he was killed at Cambrai in 1917, and under different circumstances Philip would no doubt have welcomed his lost friend to Lympne. Duff thought the house ‘charming – almost ideal for a honeymoon … the decorations are ultra modern – might not perhaps do to live with but perfect to stay in. The luxury and comfort are beyond reproach.’

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: