По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

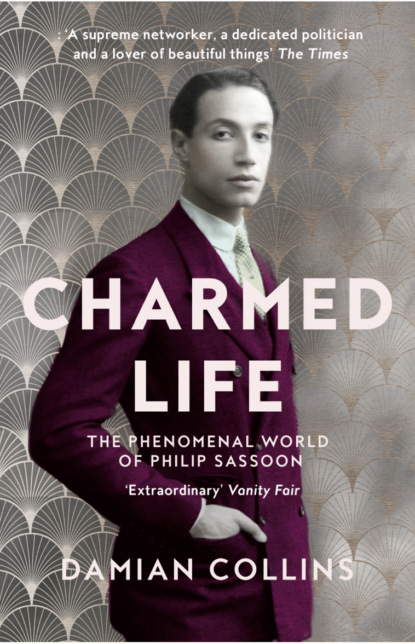

Charmed Life: The Phenomenal World of Philip Sassoon

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Lodge was a Christian spiritualist who had come to particular prominence following the publication in 1916 of his sensational book Raymond, or Life and Death.

The book detailed his belief that his son Raymond, who had been killed in action in Flanders in 1915, had communicated with him through séances that he and his wife had attended with the medium Gladys Osborne Leonard. Marie Belloc Lowndes secured the details from Sir Oliver of a medium in London and she accompanied Philip on the visit. She recalled that they

drove to a road beyond Notting Hill Gate, and stopped in front of a detached villa. We were admitted by a middle-aged woman, who led us into a room which contained some shabby garden furniture … after a few moments, the medium went into a trance, and from her lips there issued a man’s voice, describing a fall from a plane, and the instant death of the speaker. The same voice then made a strong plea concerning the future of a group of children he called the ‘kiddies’, and who, he was painfully anxious, should not be parted from their mother. Meanwhile Philip remained silent, staring at the medium. After a pause the same man’s voice as before issued from the sleeping woman’s lips. Again the accident was decried and there then followed an allusion to a pair of flying boots, which the speaker hoped Philip would find useful. When we were back in his car, Philip Sassoon turned to me and exclaimed, ‘The voice which spoke to me was the voice of the man who was killed flying in Egypt.’ Did you understand the allusion to his flying boots? He said, ‘Of course I did. I bought his flying boots after his death.’

On 29 October 1915 Philip was in Folkestone harbour, ready to return to France after a brief period of home leave. He waited to board his ship at the simple café on the harbour arm, which catered for service personnel. It was run by two sisters, Margaret and Florence Jeffery, and Mrs Napier Sturt, who dispensed free refreshments and kept visitors’ books which they asked all their guests, servicemen and statesmen of all ranks, to sign. Philip was happy to oblige along with the group of staff officers with whom he was travelling.

Looking around, he could see how Folkestone had been transformed by the war. It had been an elegant resort town from where the wealthy had journeyed to the continent on the Orient Express, which had descended with its passengers into the harbour station. Now it was the major embarkation point for servicemen to France, and over ten million soldiers would pass through the town on their way to and from the trenches of the Western Front. In addition to this the town was home to tens of thousands of Canadian servicemen stationed at Shorncliffe Barracks, and thousands of refugees from Belgium who had fled from the advancing Germans in August 1914.

The pre-war world was gone for ever and in October 1915 it wasn’t clear when peace would return, or if Britain and its allies would be victorious. The Germans were winning against the Russians in the east, and in the west they were fighting in French and Belgian territory, not on their own soil. The British attempt to open up the war in the east at Gallipoli had failed and in November 1915 brought about the resignation from the cabinet of Winston Churchill, whose idea it had been. A further setback on the Western Front at the Battle of Loos created pressure for a change in the direction of the war effort, and on 3 December General Sir Douglas Haig replaced Sir John French as commander of the British forces in France. This change of leadership would have a sudden and profound impact on Philip Sassoon. Haig, upon taking up his new post, invited Philip to work for him as his private secretary at GHQ. The war had now given Philip something he had sought in peacetime – a chance to perform a meaningful role at the centre of great events.

On 31 March 1916 Haig established his personal headquarters at the Château de Beaurepaire, in the hamlet of Saint Nicolas, a short distance from the beautiful town of Montreuil-sur-Mer, and about 20 miles south of Boulogne. The communications nerve centre of GHQ was based in the historic Citadel at Montreuil, but the whole town became an English colony for the remainder of the war. The Officers’ Club in the Rue du Paon was believed to have one of the best wine cellars in Europe,

and tennis courts were constructed between the ramparts that surrounded the Citadel.

Montreuil was chosen because it was centrally placed to serve as the communications centre for forces across a front stretching from the Somme to beyond the Belgian frontier. It was also a small town of only a few thousand inhabitants, and no great distractions for the officers and men stationed there.

Montreuil and the Château de Beaurepaire would be Philip’s principal base for the rest of the war, although for the launch of new battle offensives GHQ could move to an advanced position, often in a house closer to the front line, or in some railway carriages parked in a nearby siding. Philip would also accompany Haig to conferences of the British and French leaders and represent him at meetings in London and Paris. There was a dynamism to working for Haig that suited Philip’s energetic personality: cars and drivers on standby to rush between meetings, special trains and steamships ready to convey the ‘Chief’ at any hour, the King’s messenger service available for the express delivery of important messages or specially requested luxury items for an important dinner.

Philip’s working routine was set around Haig’s. He would be at his desk before 9 a.m. each morning, breaking at 1 p.m. for lunch, which lasted for half an hour. In the afternoon, Philip would typically accompany Haig to meetings at GHQ or to visit ‘some army or corps or division’ in the line.

After returning to Beaurepaire they worked up to dinner at 8 p.m., then went back to the office at 9, until about 10.45 p.m. Brigadier-General John Charteris, who was Haig’s Chief Intelligence Officer, remembered that ‘At this hour [Haig] rang the bell for his Private Secretary, and invariably greeted him with the same remark: “Philip – not in bed yet?” He never changed this formula, and if, as did occasionally happen, Philip was in bed, he always used to say to him next morning: “I hope you have had enough sleep?” There were only rare occasions when this routine of the Commander-in-Chief’s day was broken by even a minute.’

Sassoon and the general developed a good working relationship, and Haig came to regard Philip as a ‘very useful private secretary’.

Robert Blake, who would later edit Douglas Haig’s private papers, noted that ‘Haig did not talk much himself but he enjoyed gaiety and wit in others, and he appreciated conversational brilliance. This partly explains his paradoxical choice of Philip Sassoon as his private secretary.’

There was criticism from some of the other staff officers of Haig’s decision. Philip was in their eyes a politician who had not been trained at Sandhurst like the rest of them, or seen any military service, yet he was now to have privileged access to the Commander in Chief at all hours. According to Blake, they saw Philip as a ‘semi-oriental figure [who] flitted like some exotic bird of paradise against the sober background of GHQ’.

Some also felt he had been preferred because his uncle Leopold Rothschild was a friend of Haig’s. Leopold, with Philip’s assistance, would certainly make sure that Haig was kept well supplied with food parcels from his estate, which may have added credence to these mutterings.

Philip’s appointment was due in part to the reputation he had earned during the war as an efficient and effective staff officer; but there were plenty of those for Haig to choose from. As a fluent French-speaker, and a relative of the French Rothschilds, Philip was also able to assist in the liaison between Haig and the military commanders and senior politicians of France. His contacts in Westminster and the London press were similarly invaluable. Douglas Haig had learnt from the removal of Sir John French as Commander in Chief that the position of a general in the field could soon become vulnerable without powerful supporters at home.

But while Philip knew the leading politicians in London, he had not yet established himself as a figure in their world. In January 1916 Winston Churchill visited Haig at GHQ, which he found deserted, except for Sassoon sitting outside the Chief’s office, ‘like a wakeful spaniel’.

As a former serving officer in the Hussars, Churchill, free from ministerial responsibility, now wanted a command on the front line in France. A few days after Churchill’s visit, Philip wrote to H. A. Gwynne, the editor of the Morning Post, informing him that ‘Winston is hanging about here but Sir D. H. refuses to give him a Brigade until he has had a battalion several months. It wouldn’t be fair to the others and besides does he deserve anything? I think not, certainly not anything good.’

Philip was now in the front line of the war within the war – that between Britain’s leading politicians and the military commanders in France over the direction of the conflict. At its heart was an argument that continues to this day: whether it was poor generalship or poor supply that was prolonging the war. One of Philip’s allies in this new front was Lord Esher, a member of the Committee for Imperial Defence, who had been an éminence grise in royal and military circles for many years. Regy Esher ran an informal intelligence-gathering network based on gossip and insight collected from his well-connected friends in London and Paris. His style and experience suited Philip perfectly. Esher was also a sexually ambiguous character, who made something of a habit of befriending young men like Philip Sassoon. There is no romance in their letters, which while full of gossip were largely focused on the serious matter of winning the war. However, Philip certainly opens up to Regy, suggesting a strong mutual trust, and a relationship similar to those he formed with other older friends, who became a kind of surrogate family for him. One letter in particular to Esher is full of melancholic self-reflection. ‘To have slept with Cavalieri [Michelangelo’s young male muse], to have invented wireless, to have painted Las Meninas, to have written Wuthering Heights – that is a deathless life. But to be like me, a thing of nought, a worthless loon, an elm-seed whirling in a summer gale.’

Esher advised Philip on the importance of his role as a gatekeeper and look-out for the Chief against the interference of government ministers in Whitehall. He told him in early 1916 that the ‘real crux now is to erect a barbed wire entanglement round the fortress held by K,

old Robertson

and the C[ommander] in C[hief] … But subtly propaganda is constantly at work.’

This ‘propaganda’ was emanating from Churchill, F. E. Smith

and David Lloyd George, who had started to question the strategy of the generals; in particular they shared a growing concern at the enormous loss of life on the Western Front for such small gains, and debated whether some other means of breaking the deadlock should be found. The generals on the other hand firmly believed that the war could be won only by defeating Germany in France and Belgium, and were against diverting resources to other military initiatives. Churchill in this regard blamed Lord Kitchener and the generals in France for the failure of his Gallipoli campaign, because he felt they had not supported it early enough and with the required manpower to ensure success.

These senior politicians also believed that the generals were seeking to undermine confidence in the government through their friends in the press, so that any blame for military setbacks fell on the ministers for their failure to supply the army with sufficient trained men, ammunition and shells. Churchill was highly critical of what he saw as

the foolish doctrine [that] was preached to the public through the innumerable agencies that Generals and Admirals must be right on war matters and civilians of all kinds must be wrong. These erroneous conceptions were inculcated billion-fold by the newspapers under the crudest forms. The feeble or presumptuous politician is portrayed cowering in his office, intent in the crash of the world on Party intrigues or personal glorification, fearful of responsibility, incapable of aught save shallow phrase making. To him enters the calm, noble resolute figure of the great Commander by land or sea, resplendent in uniform, glittering with decorations, irradiated with the lustre of the hero, shod with the science and armed with the panoply of war. This stately figure, devoid of the slightest thought of self, offers his clear far-sighted guidance and counsel for vehement action, or artifice, or wise delay. But this advice is rejected; his sound plans put aside; his courageous initiative baffled by political chatterboxes and incompetents.

In 1916 Philip Sassoon would be the most significant of those ‘innumerable agencies’, taking on the responsibility for liaising with the media on behalf of Douglas Haig. His most important relationship was with the eminent press baron Lord Northcliffe, owner of The Times and the Daily Mail, whose regard for military leadership was as great as his general contempt for politicians. Northcliffe had started from nothing to become the greatest media owner of the day, and could boast that half of the newspapers read every morning in London were printed on his presses. He was at this time, according to Lord Beaverbrook’s later account, ‘the most powerful and vigorous of newspaper proprietors’.

Philip had the emotional intelligence to understand that the great press baron expected to be appreciated. He would facilitate Northcliffe’s requests to visit the front or for his journalists to have access to interview Haig. Philip would also write to thank him for reports in his papers that had pleased GHQ. The great lesson that Philip would learn from Northcliffe was that even people who hold great office cannot fully exercise their power without the consent of others, and that consent is based on trust and respect. The press had the power to apply external pressure which could lead people to question the competences of others. In this way they had helped to bring down Sir John French, and forced Prime Minister Asquith to bring the Conservatives into the government.

Northcliffe had complete faith in the army and in the strategy of the generals to win the war on the Western Front. He wanted to deal directly with Haig’s inner circle, and he knew that when he was talking to Philip Sassoon he was as good as talking to the Chief. Philip had good reason as he saw it to give his full support to Haig, and this was not just motivated by personal loyalty. Lloyd George had a reputation as a political schemer who had been the scourge of many Conservatives.

Churchill was also hated by many Tory MPs for leaving their party to join the Liberals (in 1904), a decision that seemed to them to have been motivated by opportunism and desire for government office rather than by any high principle. After the failure of Gallipoli and Churchill’s resignation from the cabinet, Philip was also clear with Northcliffe that he was no Churchill fan, and was against his return to any form of influence over the direction of the war, ‘with his wild cat schemes and fatal record’.

In early June 1916 Philip stepped ashore at Dover with Haig after a stormy Channel crossing from Boulogne which had left him terribly sea sick. On seeing the news that was immediately handed to the Commander in Chief, any remaining colour would have drained from his complexion. Lord Kitchener, the hero of the Empire and the face of the war through the famous army-recruitment posters, was dead. He had drowned when the armoured cruiser HMS Hampshire, which was conveying him on a secret diplomatic mission to Russia, sank after striking a mine off the Orkney Islands. Philip had got to know Kitchener only since joining Haig’s team and found him to possess, ‘apart from his triumphant personality – all those qualities of sensibility and humour which popular legend has persistently denied him. He dies well for himself but how great his loss is to us the nation knows well and some people in high places will learn to realise.’

Kitchener’s death blew a hole in the ‘barbed wire entanglement’ Lord Esher wanted to see protecting the military command from the politicians. Worse still, as far as GHQ was concerned, he was replaced as Secretary of State for War by Lloyd George.

The Battle of the Somme, which started on 1 July, brought further heavy losses on the Western Front: there were 60,000 casualties on the first day, with 20,000 soldiers killed. This was the worst day of casualties in the history of the British army, yet Haig was determined to press on with his campaign. Later in the month GHQ decided to mobilize press support for Haig ahead of any attempt by the new Secretary of State to interfere in military strategy. Philip Sassoon arranged for Lord Northcliffe to stay at GHQ, and he set up a meeting for him with Haig. The success of this encounter, Philip told Lord Esher, ‘will prove as good as a victory … One must do all one can to direct press opinion in the right channel.’

Although he was sometimes baffled by the interest of the press in the day-to-day trivia of Haig’s life at GHQ, he remarked to Esher that ‘Apparently the British public have much more confidence in him now they know at what time he had breakfast.’

Haig was more than happy with the initial results, noting with pleasure in a letter to his wife that his name was ‘beginning to appear in the papers with favourable comments! You must think I am turning into an Advertiser!’

Northcliffe wanted Philip to stay in contact with him over the summer while he was holidaying in Italy and told him to send messages via the British Embassy in Rome and his political adviser in London, Geoffrey Robinson. He encouraged Philip to stay close to Robinson and to allow him to come and visit out at the front. He told him that Robinson was his closest adviser on the thoughts and actions of members of the cabinet: ‘It is our system that he should know them and I should not, which we find an excellent plan. They are a pack of gullible optimists who swallow any foolish tale. There are exceptions among them, and they are splendid ones, but the generality of them have the slipperiness of eels, with the combined vanity of a professional beauty.’

The opening barrage from the politicians was delivered by Winston Churchill, who after leaving the cabinet had served at the front in early 1916, but by the summer had returned to London to speak up in the House of Commons as the champion of the soldiers serving in the trenches.

On 1 August he prepared a memo for the cabinet, which was circulated with the help of his friend F. E. Smith. Churchill argued that, following the start of the Battle of the Somme, the energies of the army were being ‘dissipated’ by the constant series of attacks which despite the huge losses of life on both sides had failed to deliver a decisive breakthrough.

This memo immediately captured the attention of Lloyd George. Robertson, the Chief of the Imperial General Staff, tipped off Haig that ‘the powers that be’ were beginning to get a ‘little uneasy’ about the general situation, and Haig prepared a note in response to Churchill’s criticisms which was circulated to the War Committee, the cabinet committee that oversaw the national contribution to the war effort.

The King visited GHQ on 8 August and discussed Churchill’s paper with Haig in detail. Haig recalled in his diary that he had told King George ‘that these were trifles and that we must not allow them to divert our thoughts from the main objective, namely “beating the Germans”. I also expect that Winston’s head is gone from taking drugs.’

Philip Sassoon heeded Northcliffe’s request to keep him informed of developments at GHQ and wrote to tell him that ‘We have heard all about the Churchill Cabal from the King and his people who are out here this week … The War Committee are apparently quite satisfied now at the appreciation of the situation which the Chief had already sent them and proved a complete answer to Churchill’s damnable accusations.’ Philip then added suggestively, ‘Lloyd George is coming to dine here Saturday night. I shall be much interested to hear what he has to say. I do trust that he and Carson

will be made to realise how damaging any flirting with an alliance with Churchill would be for them. Do you think they realise this? Sufficiently?’

On 14 August Lord Esher wrote to reassure and warn Philip that

No combination of Churchill and F. E. can do any harm so long as fortune favours us in the field. These people only become formidable during the inevitable ebb of the tide of success. It is then that a C in C absent and often unprotected by the men whose duty it is to defend him, may be stabbed in the back. It is for this reason that you should never relax your vigilance and never despise an enemy, however despicable.

Philip certainly had complete faith in Haig’s strategy and the ongoing Battle of the Somme, writing to his uncle Leopold Rothschild the same day, ‘Everything is going very satisfactorily here and the whole outlook is good. If we can, as I hope, keep up combined pressure right into the autumn, the decision ought not to be far off.’

During Lloyd George’s visit to GHQ he reassured Haig that he had ‘no intention of meddling’.

Yet, the following month, news reached Haig directly from the French commander General Foch that Lloyd George had been asking his opinion about the competence of the British commanders. Haig could not believe that ‘a British Minister could have been so ungentlemanly as to go to a foreigner and put such questions’.

Philip Sassoon was given a full debrief on Lloyd George’s visit to see Foch, which could only have come directly from Haig, and he immediately set to work on Northcliffe. His response was designed to be personally wounding, saying that Lloyd George’s visit to both the British and French headquarters had been a complete ‘joy ride from beginning to end’. He also told Northcliffe that Lloyd George had been discourteous by keeping General Foch waiting an hour and a half for lunch, without giving an apology, and then he had asked him why the French guns were more effective than the British, which Foch refused to answer. Lloyd George also found only fifteen minutes of private time for Douglas Haig during his visit. ‘If this is the man some people would like to see PM,’ Philip told Northcliffe, ‘I prefer old Squiff

any day with all his faults. It is my private opinion that he has neither liking nor esteem for the C in C. He has certainly conveyed that impression to all. No doubt Churchill’s subtle poison has done its deadly work.’