По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

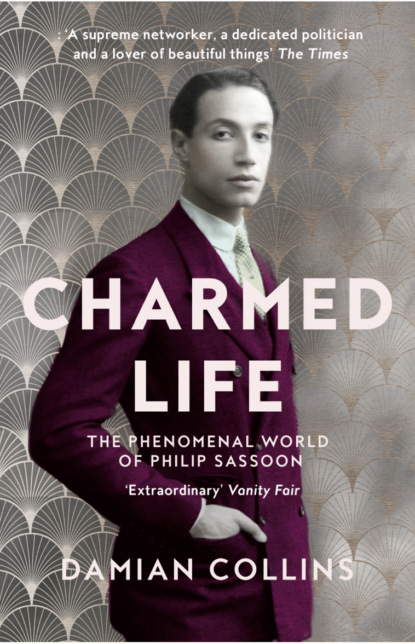

Charmed Life: The Phenomenal World of Philip Sassoon

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He could certainly rely on the support of the Folkestone fishermen, who had carried Edward Sassoon’s banner and party colours on their boats moored in the harbour at the general election in 1910, and did the same during Philip’s campaign. They were set against the Liberal government’s free-trade policies that allowed French fishermen to land their fish in Folkestone tariff free, while British vessels were charged if they brought any of their catch into French ports. Philip also received backing from the licensed victuallers in the constituency, continuing the traditional support the Tories enjoyed from the drinks industry.

He upset some of the more traditionalist Conservative MPs during the by-election by supporting the suffragette campaign for votes for women. At his first public meeting of the campaign, he was accused by some in the audience of being too young, but the newspapers reported that he ‘promised to grow out of that if they gave him the chance’.

His performance at the meeting was also reported by the local newspapers as an ‘amazing success’.

On polling day the weather was fine, which was good for encouraging voters to turn out and, just in case, Philip’s campaign used motor cars to drive their supporters to the polling stations. The voters of the Hythe constituency safely returned to Parliament the young man they had known since he was a boy, with a majority almost exactly the same as his father had enjoyed at the previous general election. At the age of just twenty-three, Philip also had the distinction of being the ‘baby of the House’.

Contemporaries of Philip’s such as Patrick Shaw Stewart were working to make their fortune, with the hope later of taking a seat in Parliament. Sir Philip Sassoon had now secured both through inheritance. Edward Sassoon’s vision of the life that was to open out for Philip had come to pass, but while the efforts of his ancestors could help to deliver him to the House of Commons, he would have to make his own reputation once there.

Max Beerbohm, the well-known satirist of the politicians of the day, depicted a sleek and impassive Philip Sassoon sitting cross-legged in the lotus position on the green benches, between two large, booming and red-faced Tories.

He called the caricature Philip Sassoon in Strange Company. Philip was very different in appearance and manner from the knights of the shires and veteran soldiers of colonial wars who adorned the House of Commons. There were also very few Jewish MPs, and over 90 per cent of the Conservatives were practising members of the Church of England. But Parliament was starting to change with more businessmen and middle-class professionals, as well as the growing representation of workers and trade unionists from the Labour Party. The House of Commons Philip entered in June 1912 featured some of the greatest names in the history of that chamber, including statesmen like David Lloyd George, Arthur Balfour and Winston Churchill. It was also a time of political uncertainty as the Liberal government led by Prime Minister Herbert Asquith, whose wife Margot had been a close friend of Philip’s mother, was beginning to run into trouble. There had been Lloyd George’s great and controversial ‘People’s Budget’ in 1909, followed by the constitutional crisis over reform of the House of Lords, and the ongoing and intractable problems of the government of Ireland. The Conservatives had been in opposition for over six years, but they had high hopes of getting back into power at the next election.

Philip waited until November 1912 to make his maiden speech, speaking against the government bill on Irish home rule. Max Aitken (later Lord Beaverbrook

), the Canadian businessman, MP and newspaper proprietor, remembered that ‘It was an indifferent performance but it brought forth a flood of notes of congratulations not because he had made a good speech but because he had big houses and even bigger funds to maintain them.’

Philip looked to put these to good effect as well, by hosting a grand lunch at Park Lane before the great Hyde Park demonstration in support of Ulster loyalism, with guests including the Unionist leader, Sir Edward Carson, and senior Conservatives like Lord Londonderry, F. E. Smith and Austen Chamberlain. Philip’s Unionist credentials were further established when it was reported that at a speech in Folkestone he had suggested that he would pay for a ship to take local army reservists to Ireland to support the cause of Ulster remaining free from the interference of home rule government in Dublin – although it was a promise that he later denied having made.

These actions may reflect his early ambitions in politics and a desire to make a good impression, rather than a genuine conviction on his part. He was trying to be helpful in aligning himself with issues close to the heart of the leadership of the Conservative Party, but he otherwise made no great impression in Parliament in his first two years in the House of Commons. He certainly became much more liberal in his views on issues like Irish home rule after the war.

The years 1912 and 1913 marked a turning point in Philip’s life, and that of his sister Sybil. With their parents gone, youth had ended and adult life had been thrust upon them. This also brought them closer together. Sybil had been educated in Paris, while Philip was at school in England. Now they would both live in London. In 1913 Philip and Sybil had individual portraits painted by the family friend, John Singer Sargent, who captured their beauty and poise, presenting them both on the brink of fulfilling their youthful promise. More interesting was a second portrait Philip commissioned from his friend the young artist Glyn Philpot. In this darker painting Philpot depicts Sassoon dressed in the same formal clothes as in the Sargent portrait, but instead of looking away and into the distance, Philip’s head is turned and lowered a fraction to look at us. While still elegant, he appears a more human, lonely and less certain figure, carrying the weight of the responsibilities that have been placed upon him.

On 6 August 1913 Sybil, at nineteen, was married after a brief courtship to George, Earl of Rocksavage, the dashing heir of the Marquess of Cholmondeley. Philip had introduced Sybil to ‘Rock’; they had known each other through their mutual friend Lady Diana Manners. Sybil’s marriage added to Philip’s relative isolation at this time. She would depart on a honeymoon of almost a year in India, and when they returned set up home at Rock’s family estate in Norfolk, Houghton Hall, and their townhouse at 12 Kensington Palace Gardens. The marriage also caused a severe rift with many of their Jewish relations, particularly the Rothschilds, who took exception to Sybil marrying outside their religion. Philip gave his sister away, and their great-aunt Louise Sassoon and cousin David Gubbay were witnesses, along with Rock’s father, the Marquess of Cholmondeley. None of Sybil’s Rothschild relations attended the ceremony and they would have no contact with her for many years. The wedding was a quiet affair, and took place at Prince’s Row register office, off Buckingham Palace Road in central London. The ceremony lasted only a quarter of an hour and there were no more than ten guests, who were themselves outnumbered by the pressmen and photographers waiting for them outside.

Before her marriage, Sybil had often accompanied Philip to parties and West End first-night performances. She had also supported him at dinners and the entertainments he gave at home at Park Lane. Philip never married, and would often insist that he had been so spoilt by his charming sister that no other woman could match up to her. However, while there is no definitive proof either way, the suspicion has always been that the real reason why Philip Sassoon never married was that he was gay.

Homosexuality remained illegal in the United Kingdom until 1967, and even the word itself was considered taboo during Philip’s lifetime.

He was in any case a very private man who did not like to discuss his personal affairs, but for it to have been generally known that he was gay would have caused a scandal. The writer Beverley Nichols recalled that ‘there were still a large number of people – particularly in high places – to whom the whole of this problem was so dark, so difficult and so innately poisonous, that they instinctively shut their eyes to it’.

In 1931, when King George V was confronted with the news that Earl Beauchamp, a friend who had carried the Sword of State at his coronation, was in danger of being exposed as a homosexual, he exclaimed, ‘I thought men like that shot themselves.’ The Earl escaped prosecution but was required to live most of the rest of his life in exile from England.

,

Yet the trial of Oscar Wilde for ‘gross indecency’ in 1895 showed that just because homosexuality was illegal, that didn’t mean it was unheard of, even if it was ‘the love that dare not speak its name’.

In fact after the First World War in ‘university circles’ Oscar Wilde was considered to be something of a ‘martyr to the spirit of intolerance’.

The writer Robert Graves, seven years Philip’s junior and a friend of his distant cousin Siegfried Sassoon, believed that at that time ‘Homosexuality had been on the increase among the upper classes for a couple of generations,’

and in part he blamed the public school system. Graves also discussed homosexual experiences in a very matter-of-fact way in his memoir Goodbye to All That. Eton was considered to be ‘perhaps the most openly gay school of the era’,

but Philip Sassoon’s contemporary Lawrence Jones believed that at Eton ‘homosexuality [was] a mere substitute for heterosexuality. It would not exist if girls were accessible. It was not carried beyond that leaving day.’

This idea was also expressed by another Old Etonian friend of Philip’s, Lord Berners, who wrote in his memoirs:

There can be no denying that in the Eton of my time a good deal of this sort of thing went on, but to speak of it as homosexuality would be unduly ponderous … I can only say that, in all cases of which I have been able to check up on the subsequent history, no irretrievable harm seems to have been done. Some of the most depraved of the boys I knew at Eton have grown into respectable fathers of families, and one of them who, in my day, was a byword for scandal has since become a highly revered dignitary of the Church of England.

Many of Philip’s friends in the inter-war period were, however, either gay or bisexual, including Berners himself, Glyn Philpot, Philip Tilden, Bob Boothby, Cecil Beaton, Rex Whistler, Noël Coward and Lytton Strachey. During a First World War military service tribunal, when Strachey was asked, ‘Tell me, Mr Strachey, what would you do if you saw a German soldier trying to violate your sister?’, he famously replied, ‘I would try to get between them.’

Sassoon was certainly at home in the private and bohemian world these men enjoyed, but he also had many close friendships with women, in particular with the writers Marie Belloc Lowndes and Alice Dudeney, and the garden designer Norah Lindsay. These relationships were not romantic, mostly based on mutual interests and an easy personal rapport. Alice Dudeney did note one occasion in her diary while staying with Philip in Park Lane, when he was ‘very restless’, and told her, ‘I’m one of those people who can’t say things. I want helping out.’ Alice recalled that, at the end of their conversation, Philip ‘just laughed and stooping kissed me – for the first time. I was very much stirred as – clearly – was he.’

There was certainly no affair between Philip and Alice, who was by her own admission old enough to be his mother, but this episode gives an insight into the difficultly that he had in expressing his feelings towards others. This could have been the result not just of his Edwardian childhood, but also of the loss of his parents before he had reached emotional maturity.

Philip Sassoon’s surviving personal papers provide little concrete evidence of his private life. In 1919 he kept a travel diary of a tour of Morocco and Spain he made with a friend referred to only as ‘Jack’, who had apparently been a fellow staff officer at General Headquarters during the First World War. There are also a few undated letters to Jack, with one including this passage, heavy with romantic overtones, ‘So you waited all the day & all the evening to ring me up … But I’ll be even with you. I’ll ring you up tomorrow morning – very early … before even the rosy fingered dawn has caused your white pyjamas to blush … I’ll wait until you are weak unwoken & at my mercy.’

Whatever the truth about Philip’s personal life, the one thing we can say with certainty is that while he had close and loyal friends, there was no one whom he shared his life with romantically over any meaningful period. There was no special partner whose relationship with him could be understood, if not acknowledged. His personal life was something that he shut away from the world; it was a part of himself that he sought to hide. One of the lessons he had learnt at Eton was that, while you could be whoever you wanted to be, there were still expectations of external conformity in Edwardian England. However, in private, and particularly at the estate he created for himself at Lympne, Philip, according to Bob Boothby, ‘gave freer rein to the exotic streak that was in him’.

Philip began work on the estate shortly after his father’s death, when he sold Shorncliffe Lodge and purchased 270 acres of farmland at Lympne, commanding excellent unbroken views of Romney Marsh and the English Channel beyond. The location was probably the best on the south Kent coast, and the whole estate was set into a secluded natural amphitheatre, created by an ancient cliff line. Philip was attracted not only to the topography of Lympne, but to its history as well. The estate marked the site of an old Roman port, Porta Lemanis, that had slowly transformed over the last thousand years into a hilly bank, as the sea had withdrawn and the wide flat marshes formed below. Philip loved the idea of his new estate having such old foundations, rather like the history of his own family.

He appointed a fashionable architect to design the mansion, Herbert Baker, who was best known at the time for his work for Cecil Rhodes in South Africa

and had only just moved his practice to London. Sir Herbert chose a Dutch colonial style, similar to designs he had used in South Africa, with the house gable-ended and facing the sea. Philip requested that older bricks be used to give softer tones to the appearance of the house and also to make it look longer established in its setting. Years later, when the gardens had been created and Philip opened up the estate to occasional public tours to raise money for deserving charities, he delighted in retelling the remark about Port Lympne he had overheard from one of the guides, that it was ‘All in the old world style, but every bit of it sham.’

Although the main structure of the mansion was completed in 1913, further design work on the house and grounds would be interrupted by the approaching war in the summer of 1914.

2 (#ulink_20bb0934-0312-5be5-b750-e676bb61324b)

• THE GENERAL’S STAFF • (#ulink_20bb0934-0312-5be5-b750-e676bb61324b)

Fighting in the mud, we turn to

Thee In these dread times of battle Lord,

To keep us safe, if so may be,

From shrapnel snipers, shells and sword.

Yet not on us – (for we are men

Of meaner clay, who fight in clay) –

But on the Staff, the Upper Ten,

Depends the issue of the day.

The Staff is working with its brains

While we are sitting in the trench;

The Staff the universe ordains

(Subject to Thee and General French).

God help the staff – especially

The young ones, many of them sprung