По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

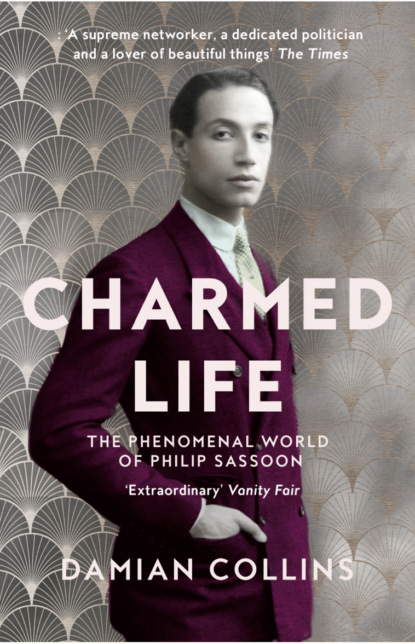

Charmed Life: The Phenomenal World of Philip Sassoon

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

From our high aristocracy

Their task is hard, and they are young.

O Lord who mad’st all things to be

And madest some things very good

Please keep the extra ADC

From horrid scenes, and sights of blood.

See that his eggs are newly laid

Not tinged as some of them – with green

And let no nasty drafts invade

The windows of his limousine.

Julian Grenfell,

‘A Prayer for Those on the Staff’ (1915)

The First World War thundered into the summer of 1914 from a clear blue sky. On the morning of 28 June the heir of the Emperor of Austria, the Archduke Franz Ferdinand, and his wife Sophie, the Duchess of Hohenberg, were assassinated in Sarajevo by a young ‘Yugoslav nationalist’, Gavrilo Princip.

,

In thirty-seven days Europe went from peace to all-out war at 11 p.m. on 4 August. People at that hour had little comprehension of the magnitude of the decision that had been made, and how it would shatter the lives of millions of people.

Doom-mongers in the press and the authors of popular fiction had, however, been predicting war for years. The growing military rivalry between the powers and the ambition of Germany in particular, they believed, would inevitably lead to conflict. H. G. Wells, a friend and near neighbour of Philip Sassoon’s in Kent, had also made this prediction in his 1907 novel War in the Air.

As relations between the nations of Europe deteriorated in late July, people started to prepare for war. On 28 July, the day Austria declared war on Serbia, Philip Sassoon’s French Rothschild cousins sent a coded telegram to the London branch of their family asking them to sell ‘a vast quantity’ of bonds ‘for the French government and savings banks’. The London Rothschilds declined to act, claiming that the already nervous state of the financial markets would make this almost impossible, but they secretly shared the request with the Prime Minister, Asquith, who regarded it as an ‘ominous’ sign.

On 3 August Philip Sassoon sat on the opposition benches of a packed House of Commons to listen to the Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey, update Parliament on the gravity of the situation in Europe. Britain stood ready to honour its commitments to the neutrality of Belgium, and to support France if it were to be the victim of an unprovoked attack. Sir Edward argued to cheers in the House that if a ‘foreign fleet came down the English Channel and bombarded and battered the undefended coasts of France, we could not stand aside and see this going on practically within sight of our eyes, with our arms folded, looking on dispassionately, doing nothing’. It was a scene that Philip could all too easily envisage, as it was one that might be observed standing on the terrace of his new house at Lympne. The prospect of a naval conflict near the Channel, and fighting on land, of the kind that the Foreign Secretary described would also place his own parliamentary constituency in south-east Kent almost exactly on the front line. For Britain to fight in defence of France, the home of his mother and where he had spent so much of his own life, would be for Philip a just cause.

His first thought following the outbreak of war was for the safety of his sister Sybil and her husband who were in Le Touquet, on the return journey from their honeymoon in India. They had stopped off there so that Rock could play in a polo match, but now there were reports of chaos at Channel ports like Boulogne, where people were trying desperately to get home. So Philip’s first act of the war was to dispatch his butler Frank Garton to France with a bag of gold sovereigns to ensure their safe passage home.

Conscription into the British army would not be introduced until 1916, but Philip was not faced with the dilemma of when or whether to volunteer for the armed forces. As an officer in the Royal East Kent Yeomanry reserve force, he received his mobilization orders the day following the declaration of war; Philip was one of seventy Members of Parliament who were called up in this way. There was no question of MPs who volunteered to fight being required to give up their seats. Philip believed that as a young man he was better placed to serve the interests of his constituents in wartime by joining up with the armed forces than by working in Westminster.

Philip’s Eton and Oxford friends, such as Patrick Shaw Stewart, Edward Horner and Charles Lister, volunteered. Julian Grenfell was already a professional soldier as a captain in the Royal Dragoons. Lawrence Jones, who also served as a cavalry officer, remembered that ‘whereas Julian went to war with high zest, thirsting for combat, and Charles with his habitual selflessness to a cause, Patrick had it all to lose … but knowing the risks, let go his hold of them and went cheerfully to war’.

Philip also went cheerfully, and even as late as 1915 he wrote to Julian Grenfell’s mother Lady Desborough from France, telling her, ‘It is so splendid being out here. The weather is foul – the climate fouler and the country beyond words and nothing doing – but it is all rose coloured to me.’

Philip did not have the swagger of a natural soldier. A fellow officer recalled walking into a French town with him when they met a young woman with bright-red hair. ‘Philip wishing to pay her a compliment said to her “vous avez de très jolies cheveux Mademoiselle”. But as he said it he tripped up over his silver spurs and fell on his face on the pavement.’

Men like Julian Grenfell were, however, in their element at the front. Grenfell wrote to his mother, ‘I adore war. It is like a big picnic without the objectlessness of a picnic. I’ve never been so well or so happy. Nobody grumbles at one for being dirty. I’ve only had my boots off once in the last ten days; and only washed twice.’

Philip did not join this band of brothers fighting at the front. He was held training with his regiment until February 1915, when he was transferred to St Omer to work as a staff officer at the headquarters of Field Marshal Sir John French, the Commander in Chief of the British Expeditionary Force. The British were fighting in alliance with the forces of France along a united front, and so coordination and understanding between the commanders was a necessity. Philip Sassoon’s family and political connections in London and Paris, as well as his perfect command of the French language, made him an excellent choice to serve on the British staff.

The staff soon became the focus of resentment among the soldiers serving at the front. While the latter endured the mud, wet, cold and death in the trenches, the staff officers operated from headquarters based at French chateaux many miles behind the lines. In the Blackadder version of the history of the First World War, staff officers like Captain Darling are characterized as being rather arrogant and effete, leading a life of relative comfort and security. Similarly in the 1969 satire Oh! What a Lovely War the immaculately dressed staff officers play leapfrog at General Headquarters (GHQ) while the men die at the front. As the war went on the soldier poets came to curse the ‘incompetent swine’

on the staff whom they blamed for the failures of military strategy, and Julian Grenfell in one of his poems went as far as to accuse some of the young officers of being too ‘green’ to fight.

Yet many staff officers lost their lives during the war, and they were at risk from direct fire, particularly from enemy shells, both when they visited advanced positions closer to the front and on the occasions when they were targeted at GHQ itself. Philip worked long hours, but while the small wooden hut at GHQ that served as his personal quarters was not at all luxurious, it was not the trenches. It was a distinction he recognized, writing to Lady Desborough during a period of particularly bad weather, ‘I can’t imagine how those poor brutes in the trenches stick it out. I simply hate myself for sleeping in a bed in a not so warm house.’

But other men of similar status had opted to serve at the front, and twenty-four MPs would be killed in action during the war. Raymond Asquith, the son of the Prime Minister, had refused a transfer to a position on the staff, and would later die leading his men in battle. Philip had simply obeyed his orders; he was mobilized at the start of the war, and until February 1915 was preparing to fight at the front. He had never sought to avoid combat, and it was his skill as an accomplished staff officer that kept him at GHQ. Nonetheless, some would later question his war record, with the Conservative politician Lord Winterton wondering in his diary after dining with Philip, ‘which is more disgraceful, to have no medals like [the Earl of] Jersey

who has shirked fighting in two wars, or to have them like Philip Sassoon without having earned them’.

After his initial placement on Sir John French’s staff, Philip was promoted to serve as aide-de-camp (ADC) to General Rawlinson, the commander of IV Army Corps. The IVth was part of the British Expeditionary Force and had seen heavy fighting in Belgium at the first Battle of Ypres, and in early 1915 would take the lead at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle. Philip had Eton in common with Rawlinson, but otherwise their lives had been completely different; the general was a professional soldier who had passed out from Sandhurst before Sassoon was born, and he had served in Lord Kitchener’s campaign in the Sudan in 1898–9. In August 1914 optimists had predicted that the war might be over by Christmas, but as the stalemate of trench warfare became established on the Western Front, the generals had to plan for a long campaign. Rawlinson believed that the war would be won only by attrition, and by early 1915 Philip agreed that the Germans would have to be driven back trench by trench until the Allies reached their border, rather than by some great breakthrough that would deliver a knock-out blow. He was also concerned that any eagerness for an early peace settlement before Germany had been clearly defeated would leave it strong enough to start another war in fifteen or twenty years.

The day-to-day reality of this strategy of attrition was found in the death toll at the front. Philip would anxiously look for the names of his friends, as each morning he went through the lists of the dead and missing. In May 1915 Julian Grenfell received a head injury from a shell fragment at Railway Hill near Ypres. The initial prognosis was positive, but his condition deteriorated and he died on 26 May at the military hospital at Boulogne. When the notice of his death was placed, The Times printed a poem he had recently completed and sent to his mother in the hope she might be able to get it published. Entitled ‘Into Battle’, it extolled the honour and glory of the fighting, with Mother Nature urging on the soldiers with the words, ‘If this be the last song you shall sing, / Sing well, for you may not sing another.’

Philip was greatly affected by the loss of Julian, but it was nearly a month before he wrote to Lady Desborough. ‘I have tried to write to you every day since Julian died, but have been fumbling for words … ever since I had known him in the old Eton days I had the most tremendous admiration for him and always regretted that circumstances and difference of age had prevented our becoming more intimate.’ Julian had been only a few months older than Philip, although he was a more senior figure in the hierarchy at Eton, and almost the epitome of the heroic Edwardian English schoolboy. Philip’s choice of words reflected the distance in their relationship, but underlined how he looked up to Julian and desired his approval. It was as if for Philip that personal acceptance by Julian represented the broader appreciation of English society of his character and ability. Philip continued his letter to Lady Desborough by quoting from the war poet Rupert Brooke, who had himself died just the month before, telling her that Julian had left a ‘white unbroken glory, a gathered radiance, a width, a shining peace, under the night’.

Julian had seemed so indestructible, it was barely credible to Philip that he could be gone. ‘Such deaths as his’, he told Lady Desborough, ‘strengthen our faith – it is not possible that such spirits go out. We know that they must always be near us and that we shall meet them again.’

There was a curious epitaph to Julian’s death a few weeks later, during the Battle of Loos. One of the reservist cavalry regiments was saddled up, night and day, in the grounds of General Rawlinson’s chateau, ready in case a breakthrough in the line was achieved and the cavalrymen would be called on to gallop through the gap. Lawrence Jones, who was among their number, recalled:

After a sleepless night spent attempting to get some shelter under juniper bushes from the incessant rain, we were gazing, chilled and red-eyed, at the noble entrance of the chateau from which we expected our orders to come forth, when a very slim, very dapper young officer, with red tabs in his collar and shining boots, began to descend the steps. It was Philip Sassoon, ‘Rawly’s’ ADC. I have never been one of those to think that Staff Officers are unduly coddled, or that they should share the discomforts of the troops. Far from it. But there are moments when the most entirely proper inequality, suddenly exhibited, can be riling. Tommy Lascelles, not yet His or Her Majesty’s Private Secretary, but a very damp young lieutenant who had not breakfasted, felt that this was one of those moments. Concealed by a juniper bush he called out, ‘Pheeleep! Pheeleep! I see you!’ in a perfect mimicry of Julian’s warning cry from his window when he spied Sassoon, who belonged to another College, treading delicately through Balliol Quad. The beauteous ADC stopped, lifted his head like a hind sniffing the wind, then turned and went rapidly up the steps and into the doorway. Did he hear Julian’s voice from the grave? … We shall never know.

Julian’s younger brother Billy was killed in action on 30 July leading a charge at Hooge, less than a mile from where Julian had been wounded. Billy’s body was never found, and without a known grave he was remembered after the war on the Menin Gate memorial at Ypres. Philip had grown up with Billy at Eton and at numerous weekend parties at Taplow, and he sat down in his quarters once again to write the most painful of letters to Lady Desborough:

It was only about a fortnight ago that I had a letter from him saying that he was so bored at being out of the line and aching to get back into the salient – I rushed up to Poperinge – but he had left that morning for the trenches – now I shan’t ever see him. This has taught me not to look ahead – but I had allowed myself somehow to look forward to Billy’s friendship as something very precious for the future – and he has left a blank that can never be filled. I look back on all the pleasant hours we spent together. I have that possession at any rate. How I shall miss him.

Philip’s words reflect the more conventional friendship he had enjoyed with Billy, compared to that with Julian, one that was not marked by the need for acceptance.

In late August 1915, Charles Lister, a lieutenant in the Royal Marines, died in the military hospital at Mudros from wounds sustained in the fighting at Gallipoli. Lister had sailed out to the eastern Mediterranean with Rupert Brooke and Patrick Shaw Stewart, and while Shaw Stewart survived this doomed campaign he would later succumb at the Battle of Cambrai in 1917 along with Edward Horner. ‘Would one ever have believed before the war’, Philip wrote to a friend, ‘that one could have stood for one single instant the load of pain and anxiety which is now one’s daily breath. I find that, although I can study the casualty list without ever seeing a name I know – for all my friends have been killed – yet nevertheless one feels as much for others as for oneself – just a blur of grief: and one wakes every morning feeling one can hardly bear to live through the day.’

The deaths of these young men led to a series of publications to commemorate their short, heroic lives. Ronald Knox quickly produced a biography of Patrick Shaw Stewart, and another book, E. B. Osborn’s The New Elizabethans, included essays on the Grenfell boys, Charles Lister and others. The title was inspired by Sir Rennell Rodd’s vision of Lister as belonging to the ‘large-horizoned Elizabethan days, and he would have been in the company of Sidney and Raleigh and the Gilberts and boisterously welcomed at the Mermaid Tavern’.

,

Not all of their contemporaries recognized these romantic portraits of their friends. Lawrence Jones recalled:

A legend has somehow grown up, that Julian was one of a little band of Balliol brothers knightly as they were brilliant who might, had they survived, have flavoured society with an essence shared by them all. As far as [Charles Lister, Patrick Shaw Stewart and Edward Horner] and Julian are concerned, the legend is very wide of the mark. Apart from their delight in each other’s company, and common gallantry in the exacting tests of the war, few men could have been less alike in temperament, character and outlook.

Duff Cooper, another Eton and Oxford contemporary, wrote to Knox to protest about his biography of Shaw Stewart. In his diary he complained, ‘He never consulted me … nor asked either me or Diana for letters. This irritates me. The book as it stands is bad and dull.’

,

Yet one of these testaments to the doomed youth of the war would remain beyond reproach – Lady Desborough’s tribute to her sons, Pages from a Family Journal. This great book, running to over six hundred pages, published in 1916, was an intimate portrait of their lives from early childhood. It was, in the words of Lord Desborough, ‘intended for Julian and Billy’s brothers and sisters and for their most intimate friends’. Upon receiving his copy, Philip Sassoon told Lady Desborough that ‘it will be a tribute for all time to those two splendid joyous boys whose loss becomes more unbearable every day. One would like to have included every letter they ever wrote … I keep rereading their letters and your accounts of them until I cannot believe that they are gone.’

For many people, this belief that their loved ones could not really be gone took them in search of the intervention of spiritualist mediums. The number of registered mediums in England would more than double by the early 1920s, compared with pre-war figures.

Shortly after the end of the war, following the death of a pilot friend in a plane crash, Philip Sassoon approached an old family friend, Marie Belloc Lowndes,

and begged her ‘to write to Sir Oliver Lodge … to ask for the address of a medium’.