По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

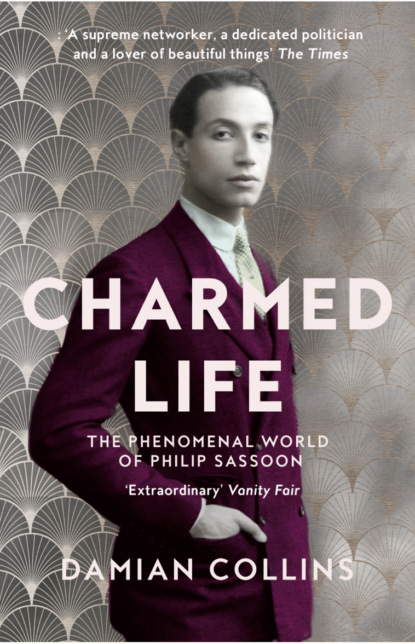

Charmed Life: The Phenomenal World of Philip Sassoon

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Philip’s intervention led to a series of articles in Northcliffe’s newspapers praising Haig and the work of the British army in France, and sniping at the ‘shirt-sleeved politicians’ who were interfering with the war. Philip’s efforts on behalf of his Chief were also coming to the attention of Lloyd George’s advisers, who warned him that Haig was ‘trying to get at the press through that little blighter Sassoon’.

The growing pressure on GHQ for a real success in the field led to the use of tanks for the first time during the later stages of the Battle of the Somme, at Pozières. The idea of an armoured trench-crossing machine had first been suggested in October 1914 by Major Ernest Swinton, who was the official British war correspondent on the Western Front. It captured the imagination of Winston Churchill, who in early 1915 urged Asquith to allow the Admiralty to develop a prototype for a ‘land ship’. To help keep the programme secret, designs were developed under the misleading title of ‘water-carriers for Russia’. When it was pointed out that this could be abbreviated to ‘WCs for Russia’, that name was changed to ‘water-tanks’, then to ‘tanks’.

Churchill had begged Asquith not to allow the machines to be used until they could be perfected and launched in large numbers and to the complete surprise of the Germans. Haig, however, was agitating to get them into the field as soon as possible, and their initial deployment in September 1916 met with limited success. Nevertheless, they caused yet more intrigue between the politicians and GHQ over who should take the credit for them. Northcliffe wrote to Philip on 2 October:

You may have noticed that directly the tanks were successful, Lloyd George issued a notice through the Official Press Bureau that they were due to Churchill. You will find that unless we watch these people they will claim that the great Battle of the Somme is due to the politicians. That would not matter if it were not for the fact that it is the politicians who will make peace. If they are allowed to exalt themselves they will get a hold over the public very dangerous to the national interests.

Lord Esher’s advice to Philip earlier in the summer, that all would be well for Haig as long as there was success in the field, was true not just for the generals but also for the politicians. The Battle of the Somme had not produced the decisive breakthrough that Philip had hoped for, and there was concern that Britain might actually be losing the war. Northcliffe decided that Asquith had to be replaced as Prime Minister, and his papers led the calls for change at the top of government. He did this not out of support for Lloyd George, who would be the main beneficiary of this campaign, but because he believed that the Asquith government was weak and a peril to the country.

There was little trust between Lloyd George and Northcliffe, and the War Secretary regarded the press baron as ‘the mere kettledrum’ of Haig.

Northcliffe would remain firmly in the camp of the generals, and the day after Lloyd George took up office as Prime Minister, he informed Philip Sassoon that he had ‘told the Daily Mail to telephone you every night at 8pm, whether I am in London or not’.

,

Philip was in London on a week’s leave during the political crisis and wrote to Haig with updates as Lloyd George’s new government took shape: ‘I think by now all the appointments and disappointments have been arranged … I think Derby’s is a very good appointment. Northcliffe said, “That great jellyfish is at the War Office. One good thing is that he will do everything Sir Douglas Haig tells him to do”! I think the whole week has been satisfactory.’

,

Philip also made good use of his London leave by arranging to meet the leading novelist Alice Dudeney, whose books he had long admired, having been introduced to her works by his friend Marie Belloc Lowndes. Alice Dudeney was well known for her romantic and dramatic fiction, often based on life near to her home in East Sussex, and would publish fifty novels in the course of her writing career. Philip managed to get her address from Marie, and wrote out of the blue to her: ‘I am such a great admirer of your books that I know it would be the greatest pleasure to me to talk to you. Would you not think it impertinent of me to introduce myself in this manner and to say how much I hope you may be able to come to lunch [at Park Lane].’

Alice duly came to lunch with Philip and Sybil the following week, and it was the start of a great friendship between them that would last the rest of his life.

Throughout the war, in what spare time he had, Philip read contemporary novels, taking up suggestions from Marie Belloc Lowndes, and getting his London secretary, Mrs Beresford, to send them out to him at GHQ. The one book that he kept constantly by his side, reading it again and again, was Marcel Proust’s Du côté de chez Swann, the first volume of À la recherché du temps perdu, which had been published in 1913. The novel’s narrator opens the story by recounting how as a boy he missed out one evening on his mother’s goodnight kiss, because his parents were entertaining Mr Swann, an elegant man of Jewish origin with strong ties to society. In the absence of this kiss he gets his mother to spend the night reading to him. The narrator says that this was his only recollection of living with his family in that house, until other sensations, like the taste of a madeleine, brought back further memories of that time. For Philip, alone in his hut at GHQ, the world before the war had become a distant memory. Perhaps as he read Proust’s lines he was trying to remember his mother’s kiss, or a weekend party at Taplow with friends who now lay dead in Flanders. Even a loud cracking noise outside, like the sound of a stock whip, might be enough to bring Julian Grenfell vividly back to life.

The British entered the new year of 1917 with little confidence that the end of the war was in sight. Philip Sassoon remained steadfast in his support for Haig (who was now a field marshal) and in a well-reported public speech during a visit back to Folkestone in January he told his audience:

They could trust their army and trust their generals. For them [the generals] the days of inexperience and over-confidence were gone. They knew their task, and they knew they could do it … the Battle of the Somme had opened the eyes of Germany, and she saw defeat in front of her. We must not be trapped by any peace snare. We had the finest army our race had produced, a Commander in Chief the army trusted, and a government they believed capable of giving vigour and decided action.

The new Prime Minister, however, had the generals in his sights. Lloyd George had formed a new government in response to growing concerns about the direction of the war, and he wanted to have some influence on the conduct of operations on the Western Front. In this regard he was determined to sideline or remove Robertson as Chief of the Imperial General Staff, and Haig as Commander in Chief in France.

Philip would accompany Haig to a series of conferences in Calais, London and Paris, where Lloyd George’s plan unfolded: to create a new supreme command for the Western Front that would remove power from Haig and transfer it to the French generals above him, as well as give more autonomy to the divisional commanders in the field. Lloyd George also brought Lord Northcliffe inside his tent by appointing him to represent the government in the United States of America, on a special tour to promote the war effort. Northcliffe was delighted with his new role, and the Prime Minister then felt emboldened to perform a further coup de main by bringing Churchill back into the cabinet as Minister for Munitions.

The War Secretary, Lord Derby, wrote to Philip to complain that he ‘never knew a word about [Churchill’s appointment] until I saw it in the paper and was furious at being kept in ignorance, but you can judge my surprise when I found that the war cabinet had never been told … Churchill is the great danger, because I cannot believe in his being content to simply run his own show and I am sure he will have a try to have a finger in the Admiralty and War Office pies.’

Philip could all too clearly see the dangers of Lloyd George’s initiatives for Haig and GHQ. After the Calais conference where the Prime Minister had first set out the idea of a combined French and British supreme command, Philip warned Esher that despite the personal warmth of the politicians towards Haig, his position remained vulnerable. He wrote, ‘Everyone – the King, LG, Curzon etc. – all patted DH on the back and told him what a fine fellow he was – but with that exception, matters remained very much as Calais had left them and the future may be full of difficulties.’

It was not just the continued heavy casualties being sustained at the front; now German bombing raids on England from aerodromes in Belgium were inflicting terrible loss of life at home as well. On 25 May 1917, on a warm, clear late afternoon, German Gotha aeroplanes dropped bombs without any warning on the civilian population in Folkestone, in Philip’s parliamentary constituency. One fell outside Stokes’s greengrocer’s in Tontine Street, killing sixty-one people, including a young mother, Florence Norris, along with her two-year-old daughter and ten-month-old son. Hundreds more were injured, and other bombs fell on the Shorncliffe military camp to the west of the town, killing eighteen soldiers. The raid shocked the nation and led to calls for proper air-raid warning systems to be put in place in towns at risk of attack.

There was further controversy over Douglas Haig’s brutal offensive in the late summer and autumn of 1917 at Passchendaele in Flanders. In June GHQ had suggested to the cabinet that 130,000 men would cover the British losses that would be sustained during the course of the battle. Instead, the total number of British casualties across the whole of the front by December was 399,000. When it became clear that no significant breakthrough had been achieved, Lloyd George resumed his agitation for Haig’s removal, but a victory at the Battle of Cambrai in late November initially seemed to secure the Commander in Chief’s position. Cambrai was the first successful use of tanks on a large scale, but there was criticism that the level of success had been exaggerated by the military intelligence staff at GHQ, and then more seriously that they had tried to cover up failings on their part which had allowed the Germans to counter-attack successfully, retaking most of the territory they had lost. Two of Philip Sassoon’s Eton and Oxford friends, Patrick Shaw Stewart and Edward Horner, lost their lives in the battle.

The outrage at the missed opportunity of Cambrai, and the further unnecessary loss of life that seemed to be a direct result of poor planning on the part of the generals, shook even Northcliffe’s belief in the military leadership. The Times reported that ‘The merest breath of criticism on any military operation is far too often dismissed as an “intrigue” against the Commander-in-chief.’ It demanded a ‘prompt, searching and complete’ inquiry into the fiasco of Cambrai.

Lord Esher discreetly briefed Lloyd George at the Hôtel de Crillon in Paris on the full extent of what had happened at Cambrai, which produced a furious reaction from the Prime Minister. Esher recalled in his diary that Lloyd George

launched out against ‘intrigues’ against him. Philip Sassoon was the delinquent conspiring with Asquith and the press. I expressed doubt and said that Haig had no knowledge of such things if they existed, but Lloyd George replied that every one of the journalists etc. reported interviews and letters to him. He was kept informed of every move. He then used most violent language about Charteris … Haig has been misled by Charteris. He had produced arguments about German ‘morale’ etc. etc. all fallacious, culled from Charteris. The man was a public danger, and running Haig. Haig’s plans had all failed. He had promised Zeebrugge and Ostend, and then Cambrai. He had failed at a cost of 400,000 men. Now he wrote of fresh offensives and asked for men. He would get neither.

Philip Sassoon shared the growing disillusion over the reliability of Charteris, and after being told by Esher about his meeting with the Prime Minister wrote back that he had ‘never agreed with these foolish optimistic statements which Charteris has been putting in DH’s mouth all year but what they [the war cabinet] ought to know is that morale is a fluctuating entity and there is no doubt that events in Russia and Italy have greatly raised the enemy’s spirits’.

,

Lord Derby told Haig that the war cabinet had no confidence in Charteris and wanted him to be removed from his position. He added that in his opinion practically the whole army considered Charteris to be ‘a public danger’.

The following day Lord Northcliffe weighed in against him as well. He warned Philip Sassoon, ‘I ought to tell you frankly and plainly, as a friend of the Commander in Chief, that dissatisfaction, which easily produced a national outburst of indignation, exists in regard to the Generalship in France … Outside of the War Office I doubt whether the High Command has any supporters whatever. Sir Douglas is regarded with affection in the army, but everywhere people remark that he is surrounded by incompetents.’

The message was duly delivered to Haig, who acknowledged that it was impossible to continue to support Charteris when he had ‘put those who ought to work in friendliness with him against him’.

Charteris was gone the same day. Philip had little sympathy for him, telling Lord Esher that ‘rightly or wrongly he was an object of odium and his name had become a byword even at home. I hear that he has been heading a faction against me for developing the position of private secretary too much. I am diverted. I went to see DH but you know the length of my material ambitions and I would not stay on a second longer than I was wanted.’

Haig survived the crisis, but in February 1918 Robertson was replaced as Chief of the Imperial General Staff, and the following month Lloyd George achieved his aim with the creation of a supreme Allied command for the armed forces on the Western Front under the French general Ferdinand Foch.

The various Anglo-French conferences during the war also gave Philip an opportunity to broaden his own circle of contacts in Paris, and one such opportunity presented itself at the Hôtel Claridge. He was attracted to successful people from a wide range of backgrounds, although the sporting, media and cultural worlds were firm favourites. One morning during a break in the conference proceedings Philip spotted across the lobby the handsome French flying ace Georges Carpentier. As Carpentier recalled:

A slim distinguished-looking gentleman with fine features came up to me and chatted to me in excellent French though with a slight English accent … Realising that he was a member of the British delegation I took out my cigarette case and said, ‘Do you know what I’d like very much? To get the autographs of Admiral Beatty, Winston Churchill and the other gentlemen on this case.’

‘That is a perfectly simple matter,’ he replied with a smile. ‘Let me have the case and I’ll give it back to you here tomorrow. Unless you would like me to leave it at your place?’

I left it with him and arranged that I should come back to Claridge’s the next day to pick it up. My unknown friend was as good as his word and when he returned my cigarette case it bore the signatures of Admiral Beatty, Winston Churchill, Lloyd George, Lord Birkenhead and Lord Montagu – and a sixth signature Philip Sassoon. ‘I took the liberty of adding my own,’ he said with a smile.

Their chance meeting was the start of another great friendship. Like Julian Grenfell, Carpentier was a boxer, and he would go on to have considerable success as a heavyweight champion after the war. He and Philip shared a passion for flying, an activity that was exhilarating, increasingly effective as a weapon of war, but also extremely dangerous. Carpentier had won the Croix de Guerre for his war exploits as a pilot, a decoration that Sassoon, along with other members of Haig’s staff, had also received from the French commander Joseph Joffre during a visit to GHQ in 1916. Philip had not flown in combat, but used aeroplanes to travel between meetings, and marvelled that he could get from GHQ in Montreuil back to his home in Kent in just forty minutes.

It was as recently as 1909 that Louis Blériot had made the first Channel crossing in an aeroplane, and there were frequent crashes even for experienced pilots. Winston Churchill was also a great enthusiast; he would often fly out to the front from London and return to Westminster that same evening to give an update to the House of Commons based on what he had seen. He considered the air to be a ‘dangerous mistress. Once under its spell, most lovers are faithful to the end, which is not always old age.’

In 1918, after his third plane crash, and the death of airmen in aircraft that he had previously piloted himself, Churchill gave in to the pressure from his family and friends to abandon his mistress. Philip, free from such domestic pressures, remained faithful to the air throughout his life, and not just because of its speed and convenience, but because in the skies he didn’t suffer from the motion sickness that made journeys by sea such an ordeal for him. Air travel also demonstrated just how close normal life was to the horrors of the Western Front. Folkestone was less than 100 miles from Ypres, and from his house at Lympne Philip could hear the guns during heavy artillery bombardments at the front.

Working alongside the high command gave Philip the opportunity to bring forward ideas of his own. One of these was encouraging famous artists to come and use their creative perspective to capture aspects of life at the front. He shared the idea with Northcliffe, who was excited by the prospect of these works capturing the everyday nobility and heroics of the men. Northcliffe credited himself with having conceived of it but praised Philip for making it happen. For Philip it was the perfect marriage of his military duties and his artistic instincts. He obtained permits for friends like John Singer Sargent and William Orpen to spend time in Belgium and France, with the freedom to paint whatever they chose. Sargent evoked a haunting beauty in his depiction of the ruins of the cathedral at Arras and great dignity in his tableau Gassed, which showed a line of men supporting each other after suffering the temporary blindness caused by a mustard-gas attack. In bad weather Philip fixed it for Sargent to tour the trenches in a tank, ‘looping the loop generally’.

He also arranged for him to meet with Douglas Haig to show him some of his work, and was greatly entertained by the juxtaposition of these two strong if mildly eccentric personalities. Philip would recall that ‘Sargent cannot begin his sentences and starts them in the middle with a wave of his hand for the beginning, while Haig cannot finish his and often concludes with hand work instead of words. In consequence, the meeting between the two was quite amusing – a series of little pantomimes.’ He also remembered taking Haig to see a remarkable picture by Sargent showing a train full of men going up to the front at twilight. Haig looked at it intently for some time and then, turning to Sargent, remarked, ‘I see – one of our light railways,’ to which the artist just smiled back in response.

William Orpen was one of the greatest portrait painters of the day; his 1916 painting of a haunted Winston Churchill after the failure of Gallipoli was Clementine’s favourite portrayal of her husband. He had also previously painted Philip Sassoon and his sister Sybil. Philip arranged for him to paint a number of the generals; in May 1917 he telephoned to invite him to paint the Chief and to come and meet him at an informal lunch at advanced HQ. Haig made a positive impression on Orpen. In the artist’s view:

Sir Douglas was a strong man, a true Northerner, well inside himself – no pose. It seemed it would be impossible to upset him, impossible to make him show any strong feeling and yet one felt he understood, knew all, and felt for all his men, and that he truly loved them; and I knew they loved him … when I started painting him he said ‘why waste your time painting me? Go and paint the men. They’re the fellows who are saving the world, and they’re getting killed every day.’

Although Philip was increasingly confident in using his position to develop his personal networks, there was one man of growing reputation he studiously avoided – his second cousin, the decorated army officer and poet Siegfried Sassoon. Siegfried was the grandson of S. D. Sassoon, the half-brother of Philip’s grandfather. While Philip was the principal male descendant of their great-grandfather David Sassoon, and the holder of the family’s baronetcy, Siegfried’s branch had become somewhat estranged from the rest of the Sassoon clan.

At that time the two cousins had never met,

but they had mutual friends, including the writer Osbert Sitwell and the painter Glyn Philpot. Philip had been an early patron of Philpot’s and, as already noted, had had his portrait painted by the artist in 1914. Philpot then painted Siegfried in June 1917, after the publication of his first volume of war poems, The Old Huntsman, had brought him to public attention. This was just before his statement calling for an end to the war was read out in the House of Commons, an episode that gave him even greater notoriety. His declaration would have come to the particular attention of Philip at GHQ, as Siegfried was not just some pacifist poet, but an officer who had been awarded the Military Cross for his bravery in battle. Siegfried’s fame grew in June 1918 when a second volume of his poems, Counter-Attack, was published. Lord Esher asked Philip, ‘By the way, who is Siegfried Sassoon? Tell me, and do not forget. He is a powerful satirist. Winston knows his last volume of poems by heart, and rolls them out on every possible occasion.’

Philip initially ignored Esher’s question but, when he wrote asking again, confirmed that Siegfried was a distant relation. Philip would have found the war poet’s work embarrassing, with its constant references to the bravery of the men, the brutality of the military commanders and the incompetence of their staff officers. One poem in particular that Churchill had committed to memory was ‘Song-Books of the War’, with its lines:

And then he’ll speak of Haig’s last drive,

Marvelling that any came alive

Out of the shambles that men built

And smashed to cleanse the world of guilt.