По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

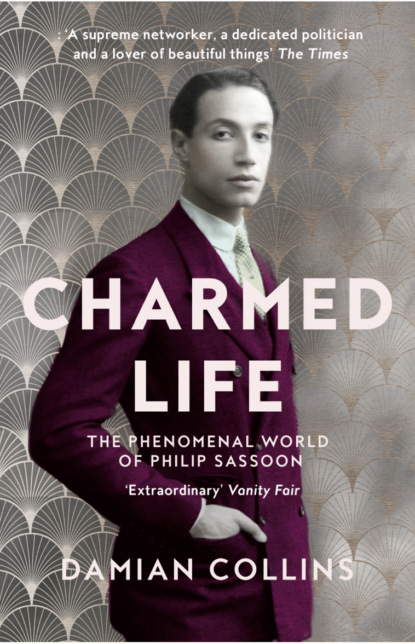

Charmed Life: The Phenomenal World of Philip Sassoon

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Yet Siegfried was just as damning of the politicians as he was of the generals, exclaiming in his poem ‘Great Men’:

You Marshals, gilt and red,

You Ministers and Princes, and Great Men,

Why can’t you keep your mouthings for the dead?

Go round the simple cemeteries; and then

Talk of our noble sacrifice and losses

To the wooden crosses.

The sacrifices had been great and the losses terrible. There was no doubt by 1918 that the world had grown weary of the war, but there was still no obvious end in sight. In early 1918 the British were instead bracing themselves for a massive German assault on their lines. The Russian Revolution of 1917 had heralded victory for the Germans on the Eastern Front, which would allow them to move large numbers of men and munitions over to France and Belgium. The United States had entered the war in support of the western Allies, but its troops were only just starting to arrive at the front. On 4 a.m. on 21 March, Operation Michael, the first phase of the great German spring offensive, or Kaiserschlacht (Kaiser’s Battle), was launched. Its objective was simple: to smash the British, drive them back to the sea and then force the French to surrender.

Philip and GHQ would be in the firing line of the German attack and its significance was clear to him. As he wrote to Lord Esher after the offensive had started:

This is the biggest attack in the history of warfare I would imagine. On the whole we were very satisfied with the first day. There is no doubt that they lost very heavily and we had always expected to give ground and our front line was held very lightly. We have had bad luck with the mist, because we have got the supremacy in the air, fine weather wd. have been in our favour … The situation is a very simple one. The enemy has fog, the men, and we haven’t. For two years Sir DH has been warning our friends at home of the critical condition of our manpower; but they have preferred to talk about Aleppo and indulge in mythical dreams about the Americans … We are fighting for our existence.

,

The British were being driven back, but the Germans were sustaining heavy losses. Nevertheless, when the King visited GHQ on 29 March, Philip reflected to Esher that ‘This is the ninth day of the attack. It feels like nine years. There have been times in every day when one might have thought the game was up.’

Haig told the King of his concern that, while the British army had held up well, its position had been compromised by decisions made by the politicians. They were fighting a German army vastly superior in size with 100,000 fewer of their own men than the year before, and over a longer section of front line. This was a result of Lloyd George’s agreement that Britain would take over some sectors that had previously been held by the French. The following day Philip wrote to Esher again: ‘We have been promised 170,000 men from home of which 80,000 are leave men. The remainder will not fill our losses and then basta [i.e. ‘enough’, from the Spanish]. Nothing to fall back on. It is serious.’

On the morning of 11 April, Haig was at his desk early, writing out in his own hand a special order for the day, which he gave to Philip with the instruction that it should be sent to all ranks of the British forces serving at the front. Two days earlier, the Germans had launched Operation Georgette, the second phase of the Kaiserschlacht, and there was no doubting that this was the critical moment of the war. Haig wrote:

Many amongst us now are tired. To those I would say that Victory will belong to the side which holds out the longest. The French Army is moving rapidly and in great force to our support.

There is no other course open to us but to fight it out. Every position must be held to the last man: there must be no retirement. With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause each one of us must fight on to the end. The safety of our homes and the freedom of mankind alike depend upon the conduct of each one of us at this critical moment.

The lines held, and on 24 April the great offensive was halted by British and Australian forces in defence of Amiens. The Germans would launch a final attack in July, but essentially their forces were spent, and with the arrival of growing numbers of fresh American reinforcements, it would just be a matter of time before victory would be delivered.

Philip came down with a dose of Spanish flu in July while on leave in London, and after resting made it to his home at Lympne for the weekend, before returning to GHQ. He was fortunate to have contracted a milder form of the virus that spread across the globe in a more virulent form in the autumn and winter of 1918–19. Over 200,000 people in Britain alone would be killed by the flu that claimed the lives of 50 million around the world.

Following the summer successes against the Germans he allowed himself to start to look forward to peace. He wrote to his friend Alice Dudeney about Lympne, ‘It was lovely there. I do want to show it to you. I am on the lip of the world and gaze over the wide Pontine marshes that reflect the passing clouds like a mirror. The sea is just far enough off to be always smooth and blue.’

At 4.20 a.m. on 8 August, having withstood all that the Germans could throw at them over the previous months, the Allies launched their own offensive. This campaign, known as the Hundred Days Offensive, commenced with the Battle of Amiens, which pushed the Germans away from their positions to the east of the town. Philip Sassoon was with Douglas Haig at advanced HQ, a train parked in the station at Wiry-au-Mont, about 40 miles west of the front line at Albert. The British broke through the lines, advancing 8 miles on what the German commander Erich Ludendorff called ‘the black day of the German army’.

Haig told his wife, ‘Who would have believed this possible even 2 months ago? How much easier it is to attack, than to stand and await the enemy’s attack!’

The Allied advance continued through the rest of the summer and by late September the Oberste Heeresleitung, the supreme German army council consisting of both the Chief of the General Staff Paul von Hindenburg and his deputy Ludendorff, told the government that the position on the Western Front was close to collapse. On 4 October the new German Chancellor Max von Baden approached the Allies with a view to agreeing an armistice to end the war, appealing in particular for the intervention of the American President, Woodrow Wilson, to act as an honest broker. As talks between the Allies and Germany continued, Philip travelled to London with Douglas Haig later that month for discussions with the French on the terms to be offered for the armistice. He told Lady Desborough after the talks, ‘We saw Foch today, he says “peace approaches”. This would certainly be the best solution of all. If only we knew and could state our peace terms we could then calmly await the day of Germany’s acceptance of them. Meanwhile Wilson über alles is the Saxon chant. Everyone is furious, but helpless. We do the fighting – America reaps the harvest.’

At 5 a.m. on 11 November 1918, in a railway carriage parked in the Compiègne forest, General Foch signed the armistice agreement with Germany on behalf of the Allied forces. At 11 a.m. that day, the moment the agreement came into effect, Philip was with Haig and the army commanders at Cambrai, to share in the moment of celebration. The news of the pending armistice had reached Folkestone in Philip’s constituency, no doubt with his help. Reporting on the events of 11 November the Folkestone Express noted that

There had been quite an electric feeling about the townspeople from early morning. Folkestone was one of the first towns, although not officially, acquainted of the fact that the war was at an end. Consequently in the vicinity of the Town Hall crowds began to gather as early as nine o’clock all full of the news. The townspeople were augmented by soldiers from every part of the British Empire, and representatives of practically all our gallant Allies.

In the drizzling rain of a November morning, the town’s mayor, Sir Stephen Penfold, announced the news of the armistice ‘in a voice trembling with joy and maybe with grief at the thought of those who had gone never to return … Pandemonium reigned for some minutes, for motor horns and anything that could make a noise were used for the purpose of spreading the glad tidings. The bells of the Parish church rang out their joyous song. At once flags and bunting were exhibited.’

Philip Sassoon would have little time for rejoicing as three days after the armistice David Lloyd George called a general election for 14 December. The Prime Minister wanted an immediate mandate for the coalition government that had won the war to negotiate the peace. The Conservative leader Andrew Bonar Law agreed that candidates from his party who supported the coalition should receive a joint letter of endorsement, from both himself and the Liberal leader Lloyd George. It was the first time that such an electoral pact between parties had been organized. The endorsement letters were dismissed as a ‘Coupon’ by Herbert Asquith (now leader only of a splinter group of Independent Liberals), but it proved to be a highly effective tactic. This wasn’t the only revolutionary change to be rushed through for the election. The 1918 Representation of the People Act gave the vote for the first time to all men over the age of twenty-one, and to some women as well. Philip Sassoon had supported votes for women when he first stood for Parliament in 1912, and this reform, so long campaigned for by the suffragettes, had finally been achieved, if not yet on a fully equal basis to men.

The new Act of Parliament expanded the electorate from 7.7 million to 21.4 million; and three-quarters of these had never voted before.

The election campaign was famous for its promises that Germany would be made to pay for the war, and that there would be rewards for the people in return for their sacrifice and forbearance, most notably homes ‘fit for heroes’. Philip was still on active service with Douglas Haig at GHQ, but the Chief gave him leave to make flying visits home to campaign in his constituency. His first trip back was on Thursday 21 November, and he addressed a series of public meetings before returning to France the following Monday.

Philip was ‘enthusiastically received’ at his first election rally at a packed Folkestone town hall. Some pride was expressed by his supporters in the role he had played supporting Douglas Haig during the war. Philip, now returning to the stage of the civilian politician, set out his wholehearted support for the coalition: ‘no government’, he said, ‘but a coalition government could have won the war and I am convinced that nothing but a coalition government can secure a satisfactory peace and start the country wisely, safely and prosperously on a new path. That is why I am a coalition candidate. On some points I may not, perhaps, see eye to eye with the Prime Minister, but I leave my personal views behind.’

This speech also demonstrated the impact of the war on Philip as a politician, and his belief that things could not just go back to the way they had been in 1914. ‘The lesson of this war’, he told his listeners, ‘is that all sections of the community are dependent on one another, and why only by unselfish desire to help the common-good can happiness come.’ It was a message that his Eton friend Charles Lister, who had died of his wounds fighting at Gallipoli, would have appreciated. Charles, who had devoted much of his time to the school’s mission to the poor in Hackney Wick, would have noted the change in Philip, from the student who seemed to care only for beautiful things to the champion of opportunity for all.

In particular, Philip focused on education, care of children and their mothers, and his belief that ‘every child born should be given a chance to become a fit and useful citizen of the Empire’. He also told his audience in the town hall that housing was ‘one of the most important questions before them. It has always been important and should have been taken up before the war.’

Even on the question of home rule for Ireland, something he had campaigned against when he first entered Parliament, the war would seem to have softened his position. The Folkestone Express reported him as stating at the meeting that

He had always held very strong views and he had not abandoned them but he realised the need of a solution which would allow Ireland to build up her industrial and political prosperity. Mr Lloyd George said he would have nothing to do with any settlement which involved the forcible coercion of Ulster and on that basis he would support any measure which would bring peace and prosperity to that much troubled land.

On the Saturday after this speech at the town hall, Philip addressed an open-air meeting in the cobbled Fishmarket in Folkestone harbour. He was again given a rapturous reception and the crowd sang ‘For he’s a jolly good fellow’ as he stood on the podium. Here, from the harbour that had sent millions to fight on the Western Front, he turned his fire on the Germans. He declared that the Allies ‘had given the Germans a damned good hiding, although he thought they had not given them the hiding they deserved’, at which there were cries of ‘hear, hear’ from the crowd. He stated that Germany should be made to pay towards the cost of reconstruction following the damage it had brought about during the war.

At an eve-of-poll public meeting at the Sidney Street School in East Folkestone,

he told the audience that ‘He wanted the Germans from the Kaiser down to be punished.’

He also advocated that Germany should be permanently deprived of its colonies.

The election was held on 14 December, but the result was not declared until 28 December, to allow time for the counting of postal votes from soldiers still on active service. Philip Sassoon safely defeated his Labour Party opponent, Robert Forsyth, by 8,809 votes to 3,427.

Immediately after the election Philip went back to GHQ, where he would stay until he was demobilized on 1 March 1919. His last service for Douglas Haig would bring him to the positive attention of Lloyd George. In February he was sent to London to negotiate the terms of Haig’s retirement settlement; it was not uncommon for military leaders to receive a generous pension for winning a war. Haig was prepared to accept a peerage as part of his settlement, most probably an earldom, but would need the means to afford the estate that would be expected to go with it. Sassoon proposed to Lloyd George that Haig should receive a cash settlement of £250,000, a relatively modest sum to a millionaire like himself, and equivalent to what he had spent on Port Lympne. The Prime Minister countered with £100,000, which was the amount that was eventually agreed, plus the earldom, and the purchase of Bemersyde House in the Scottish Borders. It was a much better deal than the settlement for generals like Edmund Allenby, who received £30,000 and a peerage.

Philip had also insisted at Haig’s request that the settlement for the generals should be granted alongside the agreement on the war pensions for all servicemen. Lloyd George accepted this in principle, but the delivery of that end of the bargain took longer to realize.

GHQ had been Philip’s home for more than three years, and he had been a serving army officer for over four. He was returning to his half-finished estate at Port Lympne and a House of Commons from which he had been largely absent since war was declared. ‘I am demobilising on March 1st – but with a rather heavy heart,’ Philip wrote to Alice Dudeney,

yet there is something corpse like about GHQ now … the ashes of last night’s fire … if it had not been for the sickening consciousness of casualties I should have been very happy during the war. Soldiers are so delightful and hard work a continual interest & away from all the rumours and intrigues of the home front! But – I shall certainly not be happy in peace – and in the House of Commons with those 700 mugs to look at – ugh!! Worse than any prison.

3 (#ulink_6b2d016a-ad6f-571d-8a3e-6af7cdcafb31)

• BRAVE NEW WORLD • (#ulink_6b2d016a-ad6f-571d-8a3e-6af7cdcafb31)

All the arts and science that we used in war are standing by us now ready to help us in peace … Never did science offer such fairy gifts to man. Never did their knowledge and organisation stand so high. Repair the waste. Rebuild the ruins. Heal the wounds. Crown the victors. Comfort the broken and broken-hearted. There is the battle we have now to fight.

Winston Churchill, speech in Dundee, 26 November 1918

Philip Sassoon’s Avro 504K aeroplane charged back across the English Channel towards home.

In bright sunlight and with low cloud, it was hard to distinguish between the sea below and the sky above. With the landscape barely changing there was almost no sense of movement, as if despite the noise of the engines you were floating suspended between heaven and earth. As the pilot brought the plane down towards the airfield at Lympne the clouds cleared; below were the elegant Edwardian buildings on the clifftops at Folkestone and the steamers chugging into the harbour; ahead Hythe Bay curved away from them to the point at Dungeness. From the air at least the scars of the war at home were barely visible.

Philip’s growing passion for flying led him to purchase his own aircraft in 1919,

the same year in which the world’s first commercial air passenger service started. According to the London society column in the Evening Standard, Philip was the first man in England ‘to venture on buying and keeping an aeroplane as other people buy and keep a motor car’.