По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

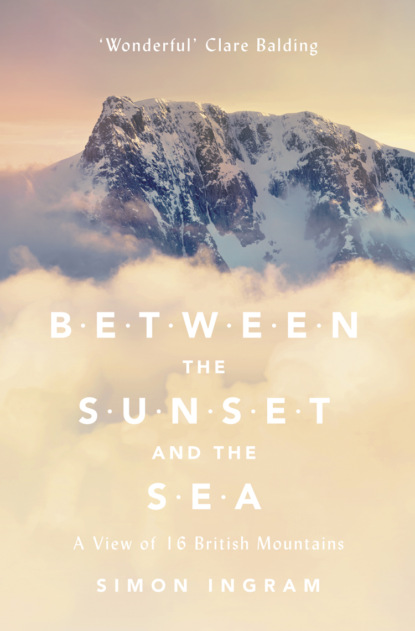

Between the Sunset and the Sea: A View of 16 British Mountains

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

11 Island (#litres_trial_promo)

12 Life (#litres_trial_promo)

13 Art (#litres_trial_promo)

14 Sport (#litres_trial_promo)

PART IV: WINTER

15 Terror (#litres_trial_promo)

16 Summit (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Selected Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

1 HEIGHT (#udee40a0e-8cb7-58c9-997d-92b4924499db)

Seven miles north of the village of Tyndrum in the Southern Highlands of Scotland the A82 flinches hard to the left and begins to climb. The pitch of your car’s engine drops. You slow. Heathery embankments recede around the tarmac and the sky begins to widen as you approach the top of a rise. The road makes a long arc like a tensioned longbow until it finds north-west then, abruptly, it snaps taut. The horizon flees around you. And ahead, beyond the sharp vanishing point of the road and softened by distance, are mountains.

These are not the elegant meringue-and-meadow peaks of the Alps, nor the shrill slants of geology you might find in density in the Himalaya or the Andes. The mountains that lie ahead of you as you drive this road are old and crouched, and etched with lines of incredible age.

The place wasn’t always like this. It’s the ghost of a once much mightier landscape. They say the ancient mountains of Scotland once stood five or six times higher – as high as the young peaks of the Himalaya stand today. Some of the oldest surface rocks in the world cover their faces and line their gullies and cracks, exposed by the millennia like dead bone to the wind. The mountains here are the ruins of a giant, explosive volcano – violent and vital. Layers of spat, hot rock layered new skin onto already ancient foundations. A million lifetimes later glaciers hung from the gaps between the peaks, carving brittle arêtes and spitting the shavings of worked land at their feet. Again and again ice and time returned to this landscape, shaping it and re-shaping it like a tinkering sculptor. He’s on a break now. Give him a few dozen millennia, he’ll no doubt be back.

This first sight as you inch into the mouth of Glen Coe never underwhelms. It’s astonishing. Even if you’ve seen it a dozen times, its magnitude is unexpected somehow. We’re constantly reminded how tiny Britain is, so it’s a surprise to find something so boundlessly big-feeling – especially to people who live in flat places where mountains don’t cut the horizon or fill the sky.

But if you’re a certain type of person, this sight carries something else, too: a kind of queer charisma. It invades the emotions and tickles something primal, enshrining mountains onto a sensory level far more stately than merely as a pretty backdrop to everything else. And if you don’t know what I’m on about, there’s an easy way you can find out: come here, drive this road, and see what happens.

You might feel nothing, of course. Maybe looking up at these mountains produces little more than a mental shrug before your mind wanders back to something more interesting inside the car. If so, best you get back to it. Where we’re going probably isn’t for you. But feel a flutter around your stomach when you enter Glen Coe – a frisson of adrenaline, an indefinable but unmistakable quickening of the pulse – and sense your eyes being tugged upwards, it’s got you. That’s it for you now. If you didn’t know it already, you’ve woken something up, and it’s never going away.

If that part of you is there, everyone’s got their own moment when they felt their mountain heartbeat spring to life. It could be something so subtle – passing through this glen or somewhere like it, watching the way evening light climbs across the buttresses of a far-off peak, the sight of windblown cloud snared and tearing from the point of a summit, the yawn of steep height against the sky. For some it remains something that stays at sea level. For others, the compulsion gets too strong, and little by little, the closer they creep.

The A82 continues into Glen Coe. The wastes of Rannoch Moor fall back from the roadside, and the mountains gather around you. Just after you pass that white cottage – the one they always put on the shortbread tins – they begin to leer over you and details emerge. The powerful gable of Buachaille Etive Mòr fills your windscreen, a side-slouched pyramid of wrinkled rock punching skyward. Grey water discharges from summits choked by cloud. All of a sudden the mountains of Glen Coe cease to resemble a distant frieze, the stumps of a range long cut down by time; they become physical and textured things, personalities almost. As your eyes trace the arêtes and buttresses, you feel deep emotions being nudged: awe, intimidation, even something implacable not dissimilar to dread.

It’s a strange thing, but it makes sense. Mountains are not the place for humanity to feel at home. They’re hostile, barren, bereft of comfort – we’re programmed as a species to avoid them. It’s a feeling as old as we are, nature’s chemical way of telling us that no, we can’t live there. It can’t sustain us. It’s cold. Hard. Find somewhere else to go. A field. A forest. A riverbank. This place isn’t for people. Mountains repel us. Fight us. Yet still, you’re being pulled closer. What would it be like, you wonder, to be up there?

The act of climbing a mountain – any mountain, anywhere – is to enter an environment that is challenging simply to be in. Up there, a vertical kilometre above you in that high ground, life is dangerously simple. Things wilt down to the basics: get up, move, keep warm, stay alive, get back. Trivialities at sea level, such as shelter and water, become coveted luxuries. All of a sudden we’re back in the state of primal essentiality that as a species humankind has been developing away from for thousands of years. It’s not like walking through the woods, or a trip to the park. Here you’re beyond the darkness at the edge of town. You’re walking back in time. It’s like anthropological nostalgia.

The things you see here in the high places become a visual drug. Once seen and felt, you’ll drive hundreds of miles just to be in this hard ancient landscape, and recapture those emotions. Spend sizeable amounts of money. Make personal sacrifices. Struggle through all weathers and dangers. And you probably won’t be able to explain why.

Some have tried, of course. There are many ‘justifications’ for climbing a mountain, some of them notoriously impenetrable, some of them shamelessly contradictory. You climb it because it’s there. You go up, to come down. None of them make much sense. Because in the pursuit of the profound, many of them compromise simple honesty: being on a mountain, a witness to its ways, just feels incredible. To hear the silence of a high stream frozen tight; to feel an ice-laden wind sizzle your skin; to stand on the prow of a mountaintop and look down on an ocean of lilac-lit clouds, whilst civilisation below slumbers beneath their shroud – and to live in a country where you can do all of this in the slender gap between Friday night and Monday morning. For anyone with even a vague appreciation of nature, climbing a mountain is a rare blessing: the closest you can get to a full-on sensory epiphany.

But mountains – particularly ours – are so much more than simply things to climb. Mountains aren’t things at all; things are just there. Mountains are places. And places are worth getting to know. Visiting. Inhabiting. Investigating. In places, things happen.

But first, something’s got to find that part of you, if it’s there. Find it, check its pulse, then really wake it up.

It was late October, and a filthy sky hung above the mountains of Glen Coe as I followed the road snaking its way between them, then continued north. Where I live in England’s east the horizon is empty of mountains; it is in fact a place particularly notable for its flatness. But this morning the skies above Lincolnshire had been full of the hard contrasts of dawn, and a solid grey weather front approaching the county from the west gave the convincing and novel impression that there was a tall, plateau-topped mountain range where there was in fact none. I allowed myself to imagine for a few minutes this wasn’t an illusion, and immediately the landscape’s entire mood shifted. Where before there had been just boundless sky, suddenly here was a presence in the landscape far more noticeable than anything else. Something to look at and, indeed, something looking back. This is the slightest dab of the feeling that fortifies the mood of the places overlooked by mountains for real. Of these, the valley of Glen Coe is perhaps the most overlooked of all – although my destination on this particular afternoon must surely run a close second.

I was driving through Scotland to Torridon, a nest of mountains in the remote North-west Highlands, to climb a peak by the name of Beinn Dearg. The summit of this otherwise anonymous hill isn’t on a lot of people’s lists of lifetime ambitions. Most people – even seasoned hillwalkers – will never climb it, particularly considering the visually throatier mountains nearby. And yet here I was, returning to climb it a second time, because ten years ago it had been Beinn Dearg that had checked my own mountain pulse.

That day the weather had been flawless. The September air was velvet warm, and blue sky and sun left the sharp mountains of Torridon entirely innocent of the malignant cloud or sudden wind so notorious in the Highlands. My companion Tom and I had sat in the breakfast area of the Torridon Inn that morning over a map of closely bunched contours when a man we correctly identified as both a local and a walker – in that he had a strong Scottish accent, shocked hair and wore a pink jacket that looked like it might once have been red – enquired as to our day’s objective.

‘Fine wee hill,’ he’d said when I pointed it out on the map.

I’d been preoccupied with the contour lines on the mountain’s western flank since the previous evening. Contours that were close together meant a steep slope; these ones were touching each other.

‘Is it difficult? It looks steep.’

‘Steep, aye. Hands-in-pockets job once you’re up, though.’

‘Hands in pockets?’

‘Aye, a bimble. Have a good day, lads.’

He winked and, with the beanpole stoop of an ageing hillwalker, was gone.

‘What does he mean?’ I hissed across the table at Tom as the door clapped shut behind him and my eyes again fell upon the closely bunched orange lines covering the map. ‘Hands in pockets? Bimble?’

Tom – who I should say was rather more experienced in such matters – was busy scrutinising the map for a parking place.

‘He means if the first bit doesn’t kill us we’ll be fine.’

Vernacular is likely to be one of your first obstacles to overcome before you feel at home in a conversation with those who climb mountains for fun. Like most niche pursuits, you’ll find yourself absorbing it as you go via a kind of linguistic osmosis. You bag summits, you don’t climb them. Tricky parts of a mountain route don’t yield: they go. You’re not off to have a walk, you’re going on the hill. Feel scared on the hill and you’re probably doing something a bit necky. The thing that’s scaring you is probably exposure. In plain English you might be reaching the summit but to a mountaineer you’re topping out. A walk is a bimble, a hard walk a yomp, something that needs hands and a strong stomach is a scramble. If it’s blowing a hoolie you don’t really want to be up there. And all of this isn’t really a walk; it’s a route. Gear is kit, sustenance hill food, anoraks shells and – just in case you get conversationally caught out – underpants are shreddies, though it’s probably best not to ask why. In addition, a certain amount of understatement is required if you want to capture the severity of the task in hand in a suitably humble manner: hence frequent use of, for example, ‘a bit rough’, ‘a lively wind’ and ‘a couple of interesting bits’ to describe something that most people would describe as twelve hours spent on a terrifying cliff in a hurricane. There’s more, but don’t worry. You’ll pick it up.

Of the ascent that took place that day in 2004, I remember three things as if tattooed with them. The first was the endless view, which carried our eyes not only over the scenically incandescent peaks of Torridon – I didn’t know their names at that point – and beyond to the Isle of Skye, where cartoonishly sharp, island-isolated peaks straddled the horizon like an open bear-trap. The second was the golden eagle we saw hunched against a crag near the mountain’s summit not twenty metres from where we were walking: a sight that stopped and silenced Tom and me in unison. We just stared at it, watching it blink, seeing the edges of its feathers quiver in the wind. Then, this beautiful, Labrador-sized thing unfurled its wings – a metre each – and nonchalantly plunged from its crag into the drop beneath it. If it moved because of our presence, it certainly didn’t make it obvious.

The third I can remember as if it happened yesterday – and was largely the reason that I was coming back to Torridon.

It had come as Tom and I approached the top of Beinn Dearg’s pathless western flank. This was the bit I’d been worried about; the bit where the contours touched. It was indeed steep, aye; not steep enough to turn walking into climbing, but steep enough to make a slip unthinkable. As we approached the point where the flank crested and tipped into a broad summit ridge – the point at which we could put our hands in our pockets and have a bimble, apparently – the mountain began to sharpen. Suddenly the ridge wasn’t something distant and removed: we were astride it. Beinn Dearg’s grassy rump gave way to ribs of naked rock, and we began to appreciate just where we were. We were no longer climbing a hill; we were nearing the top of a mountain.

From this ridge, I looked south. Ahead, beneath the level of the high balcony on which we were standing, the edge of the mountain terminated in a vertical buttress with a void beyond. It was the same feeling of compressed perspective you might get if you looked out the window of a tall building, to its edge and beyond into the far distance, something both alarming and exhilarating; a feeling of being incongruously, deeply high – out of place, out of comfort, clinging to something that is hovering amidst nothing. You’d think that being on a mountain and feeling so delicately exposed was odd, since a mountain is by its very nature a fairly solid and sizeable thing upon which to cling. But it was less what was beyond that snared that attention; it was what was beneath.

Far below a smelt of silver was catching the afternoon sun: the river. Looking at it from this height, maybe 2,000 feet above its surface, seemed so odd, so other. This was something seen from an aeroplane, or an image pulled from Google Earth. Only it wasn’t. It was the view from my own feet. Just a couple of hours ago they had carried me across a substantial bridge on that very river and then up to a perspective from which I could view this same river not as a violent cataract of spray but as a mere vein, its motion rendered still by distance. The bridge was there, too, no longer robust and impressive but a mere staple joining the banks.

It was as if I were not looking at a living scene, but a painting in which the landscape was already interpreted by the artist. Yet here, as well, were the processes of the earth, given context and meaning by height. From this elevated perch, the way the landscape interlocked and related seemed so clear.

There was the river, the valley it cut, the sea it fed, the mountains that fed it, the sky that fed them. And the mountains, falling to earth through shades of rust-red sandstone to the grey of their quartzite flanks, to the green of the lowland scored with the deep black creases of gully and ravine.

This view changed everything for me. I’d thought I had a pretty good beat on this little country, but right then I knew that nobody had really seen Britain unless they’d seen it from a mountain. How many people missed this view? Who never got to a position where they could see this kind of sight under their own steam? What percentage of the population moved through the landscape and gazed up at the mountains, without ever realising the thrill of gazing back down upon it from them? There was, of course, the question of effort and time. Of distance and difficulty. Of danger, to a degree. But to me, at that moment, this had ceased to matter. All I felt was deep and electrifying awe.

Today I now realise that day in Torridon was an almost ridiculously fortuitous introduction to the mountains. People wait all their lives for such conditions in a place like that; I felt like I’d received a concentrated dose of beginner’s luck, like buying a toy fishing rod and landing Moby Dick on the first cast. My fascination with mountains would grow and change shape over the years for me in both a passive and fumblingly active way, but I’d never shake it. That day in 2004, a part of me woke up, and one mountain journey began.