По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

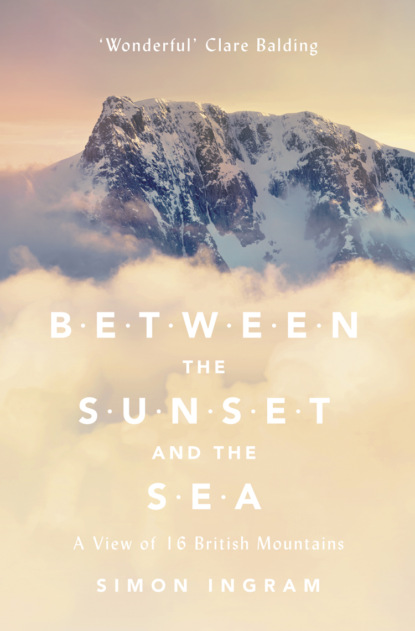

Between the Sunset and the Sea: A View of 16 British Mountains

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The eastern approach to the Black Mountain involves crossing over a mile of rough, stream-ridden heathland, more moor than mountain. The map says there’s a path here, and there might well be, somewhere – but it’s so indistinct amongst the soggy brown, lumpy grassland that following it would require constant concentration. It certainly didn’t register beneath my boots as I set off into the wind towards the dark cliff ahead.

The place to ascend from this direction is a gentle chink – the Bwlch Giedd – which from this direction dips the escarpment into a shallow ‘M’ shape. This passage is not easy to miss: at its bottom lies the large lake of Llyn y Fan Fawr – ‘Lake of the Big Peak’ – so named for its position directly beneath the highest point of the massif.

Walking into a strong wind filled with rain has little to recommend it other than giving a renewed appreciation for how desperately insignificant and fragile you are versus the elements. Within half an hour of staggering into the south-westerly, the left side of my body was beginning to feel the tendrils of cold moisture pushing through my clothing. The volatile time of year meant the usually insubstantial streams that required crossing on the journey west towards the mountain were thick and fast. The only ways across were by balancing on moss-slicked rocks over which water raced with unbalancing strength. One mis-step, and a lively second or so of spasmic body penduluming almost resulted in a dunking – after which I made a mental note to ensure to pack both a pole and a dry set of clothes were I to do anything this foolish again.

After an hour I very nearly gave up. The wind had grown stronger as I climbed above the sheltering hummocks, and it wasn’t long before it was pretty intolerable. Just walking was becoming hard, and more and more I took to stopping, mouth gaping, with my back against the wind for respite. Cloud was tearing across the vanishing mountainside ahead like billowing smoke, and with the gloom, thickening cloud and my rapidly chilling legs – plus the fact I hadn’t actually set foot on the mountain yet – the outing this was unfolding into bore little resemblance to the evocative plan I’d left home with. Just as I was considering abandoning it for another day and squelching back to the car the mist briefly moved, and I saw the shore and grey water of Llyn y Fan Fawr close by. I was practically at the base of the escarpment; it would be rude not to go and have a look at it. As I climbed towards the grey bulk of the mountain, a frayed path joined from the left. This was the Beacons Way, which climbed the escarpment of Fan Hir at precisely the point I was aiming for. Soon the red soil of the path was joined by a more established, slabby path, and as I followed it into the curl of the cliff, the wind – blocked by the fold into which the path was beginning to climb – fell away.

Suddenly it was quiet. I could hear my own whistly breathing, and my clothing – having spent the last hour energetically flapping – settled heavily against my skin. I was soaked.

The escarpment of Fan Hir isn’t a huge climb. In fact, given the relative tallness of the Black Mountain’s highest point, Fan Brycheiniog – at 802 metres the fourth-highest point in Britain south of Snowdonia – it isn’t much of a climb at all; from the shore of the lake to the top of Bwlch Giedd requires less than 150 metres of vertical ascent – vertical ascent being the typical measure hillwalkers use to anticipate the likely exhaustion of an objective. I’d parked the car at close to 400 metres above sea level; most of the rest had been gathered gently on the blustery walk in.

I stopped for a few minutes in the lee of the cliff, enjoying the calm and considering my options. Cloud was coming down and the darkness was deepening, robbing the distance of detail. From the top of the escarpment, the route to the highest point of the Black Mountain – the trig point of Fan Brycheiniog – was less than 500 metres away. I was wet as hell. Stupidly I’d neglected to pack waterproof trousers; although the ones I wore were supposedly robustly resistant, seven years of more or less constant use had evidently depleted their ability to withstand torrential rain and wind, and everything from my hips to my ankles on my left side was numb. I’d spare warm layers in my rucksack, but they were for emergencies. What’s more, I knew that once out of this sheltered fold in the escarpment, I’d be exposed to the full temper of the bludgeoning wind – wind that, quite possibly, would have the muscle to blow me clean off the top of the mountain.

I should really have called it quits, but I decided to push on to the top of the escarpment – or until my natural shelter ran out, whichever came first. If I stuck my head above the top and it was too blustery, I could turn round and climb back down without being mugged of dignity. Whether it’s Mount Everest or a Brecon Beacon, the basic physiology of a mountain can’t be argued with: the summit is only halfway home, and overstretching yourself before you’ve even made it there is usually a bad idea.

This wasn’t Everest, but it was certainly feeling extreme enough for what was originally supposed to have been a leisurely wander under the stars. I continued on up the path, and swiftly – much more swiftly than expected – I was high above the lake and approaching the top of Bwlch Giedd. Good paths make short work of ascent, and bad visibility – whilst a swine for views – can psychologically aid you, as you simply can’t see how much further you have to go.

As I reached the top of the escarpment I could feel the wind beginning to gather once more. It seemed bearable, so I tentatively carried on towards the summit. At first, the pushing gale from the south-west was robust, but not extreme; I could walk without too much trouble, albeit with a jaunty tilt of twenty or so degrees into the jet of wet air blasting the left side of me. I was now on the plateau’d top of the Black Mountain – the ‘billiard table’ – and whilst my eyes were fixed ahead for any indication of the top, I couldn’t ignore the huge drop that was now on my right. It seemed perverse that the direction of the wind was inclined perfectly to push me towards it.

In an effort to keep track of progress and stay focused, I kept pace in my head. From practice I knew that, on reasonable ground, every 64th time my left foot hit the ground I’d covered roughly 100 metres. This double-pacing technique was a staple of basic navigation, and for all my hopelessness with remembering my waterproof trousers, I knew that whenever I used this technique it was usually pretty accurate – as well as being a handy mental focus whenever things got stressful. My count was approaching 400 metres when ahead a squat rectangular shape began to solidify from out of the mist. The map didn’t indicate the presence of such, but that had to be a summit shelter. I reached it, and it was; a low, roofless horseshoe of slate, perhaps two foot high, but with its back to the wind and substantial enough to hunker inside and take stock.

The second I was beneath and away from the gale, I realised just how silly my decision to push on had been. My clothing was now so saturated my trousers were falling down with the weight of the water they had sponged up, and my sleeves hung limp around my arms. This little shelter would, most likely, have been my place of repose had I been lucky enough to catch a clear, calm night from which to appreciate the dark skies of the Brecon Beacons. But to me, right now, the thought of spending the night up here, in this weather, was chilling. I felt cold, soaked, and – however disappointed I was at not being able to reap the starry benefits of being this far from other people – truly, comprehensively alone. This was certainly an antithesis to comfort and civility, but it was starting to feel a little out of control. Were I to give up and stay here, hunkered down in this little windbreak in these conditions and the saturated state I was in, it wouldn’t be long before hypothermia began to gnaw. I can’t say the thought occurred to me at that exact moment – huddled and cold, being blasted by storm-force gales high on a mountain, miles from anywhere, with night solidifying around me – but my, what a strange way to spend a Saturday night this was. Or, put a slightly different way, what a privilege.

The safeguarding of Britain’s – and the world’s – dark skies revolves around a change in people’s thinking when it comes to their own use of light. By this reckoning, all that Britain’s wild places seemed to need in order to attain what the residents of the Brecon Beacons National Park were now obliged to do was a collective effort to reduce the amount of light pollution projected into the sky.

Something as simple as ensuring an outside light is angled downwards instead of obliquely, using a different type of lightbulb and – heavens – actually turning the things off when not being used to read the paper or shoot a burglar seemed, if embraced en masse, to be all that was needed to make a difference. In January 2012, the Somerset village of Dulverton – which lay within the other of Britain’s Dark Sky Reserves* (#ulink_9416303a-ed29-59a3-86bc-bda65fc17ba1) – staged a mass switch-off of the village lights for a live TV event to highlight the difference even a modest settlement could make. As it happened it was pouring with rain, and instead of the jolly amassed crowd cooing in wonder beneath a newly unveiled ceiling of stars, they were spooked by the opaque blackness of a night not dissimilar to the one increasing around me on the summit of the Black Mountain. The last time our cities experienced the same sort of consciously collective darkness – besides the odd power cut, during which people were presumably more preoccupied with reclaiming light than appreciating dark – was during the Blitz.

However modest, the Brecon Beacons’ new status was enough to illustrate that, as the anthropologist Margaret Mead once said, we should ‘never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.’ And when it comes to the search for space and freedom in the British mountains, it’s not just in matters of ‘light trespass’ where the actions of a few can trigger a reaction that will be influential down the generations in their enjoyment of wild places. In fact, were it not for the actions of one group in particular, weather would be the least of my barriers to experiencing the starlit skies of the Brecon Beacons; in all likelihood, I wouldn’t be there at all. Actions which, funnily enough, also involved a trespass.

Today, like all of us in Britain, I enjoy constitutional access to wild places under a law called the Right to Roam. And this is something we should be very, very proud of, on two fronts: one, that we have a country enlightened enough to have introduced such a law. And two, that it did so based on the acts of what our new friend Maggie Mead might call ‘thoughtful, committed citizens’: namely a bunch of working-class Manchester socialists who, on one otherwise unremarkable morning between the world wars, decided to go for a walk.

In 1932 Britain was a grim place if you were poor. The bite of the Great Depression was being painfully felt: industrial output fell by a third, and that summer saw unemployment hit a record high of 3.5 million – most of them casualties of the downturn in northern industries such as mining and steel. Seeking focus and amusement for little or no cost, many of the unemployed began to walk for pleasure. The problem was, this pastime – ‘rambling’ – was a play without a theatre. In 1932 there were no national parks, no long-distance footpaths. Land was owned, and enforced as such. Areas that weren’t practical for agriculture – that is to say, mountain and moorland – were ring-fenced and populated with grouse, which landowners would make available, sometimes for as little as two weeks a year, to be noisily and gleefully dispatched by those who could afford cars, guns and time to fritter.

The ‘ramblers’ were almost comical in contrast. Unable to afford specialised gear, they would improvise: army clothing, work shoes, ragged clothing they didn’t mind being ruined. In addition, many walked under the auspices of groups such as the British Workers’ Sports Federation (BWSF), which were often suffused with broader moralistic leanings – in this case, communism – and which in many people’s eyes gave the activity a disagreeable air of rascal politics.

It’s difficult today to envision the kind of restrictions early ramblers were subject to. By restrictions we aren’t talking about barred access to a few manicured grounds or fenced fields: in the early 20th century an estimated four million acres of mountain and moorland in England and Wales were owned by a few inattentive individuals who didn’t – and couldn’t possibly – make anywhere near full use of it. Paths existed for ramblers to use, but such was the uprise in popularity in the pursuit amongst the working classes (it’s estimated that in 1932 some 15,000 ramblers took leave of Manchester on a Sunday to go walking) that these were often becoming as crowded as the suburbs, and potentially problematic frustrations were starting to mount. Worse, so-called ‘respectable’ walking organisations such as the Manchester and Stockport wings of the Holiday Fellowship – via deep-running relationships with dukes, earls and other influential citizens – were enjoying the freedom to wander on land forbidden to unemployed working-class ramblers. Enjoying the countryside – whether in the form of shooting, hunting or rock climbing – was, inexorably, a perk of the privileged.

By default, the wilder places of Britain became the scene of a strange class war. Landowning aristocrats were irritated by unkempt, Catweazle-type characters drifting illegally onto their land, and ramblers were increasingly frustrated at being barred from harmlessly entering what was effectively unused wilderness a bus ride from the inner city – and all over what they saw as little more than historic, ceremonial ownership by a few Hooray Henrys. It was a dangerously unstable stand-off: the ramblers had numbers and spirit, but the landowners and gamekeepers had the written law and cash – as well as employees with guns.

One of these landowners was the Duke of Devonshire. His particular 148,000-acre patch occupied an area of northern England known as the Peak District, which – despite a name that conjures pointy drama – is largely peaty moorland and vast, open plateau, reaching its elevational zenith atop Kinder Scout at 636 metres. It’s an agreeable if bleak place to wander, and its proximity to the northern industrial cities of Sheffield, Manchester and Huddersfield made it a natural choice for ramblers seeking to escape the depressing, economically stricken cities. But in April 1932 fewer than 1,200 acres of the Peak District were open for them to enjoy. Based on our estimate that 15,000 Mancunians left the streets and took to the upland paths each Sunday, this gave each person an area of considerably less than one tenth of an acre in which to find space and tranquillity. Something had to give – and on Sunday 24 April 1932, it did.

In the weeks prior to this a scrawled leaflet found its way into the hands of interested parties on both sides of the fence. One handed out in Eccles read:

B.W.S.F. RAMBLERS RALLY

This rally will take place on Sunday 24th April at 8 o’clock. At Hayfield Recreation Ground. From the rec, we proceed on a MASS TRESPASS onto Kinder Scout. This is being organized by the British Workers’ Sports Federation, who fight:

Against the finest stretches of moorland being closed to us.

For cheap fares, for cheap catering facilities.

Against any war preparations in rambling organisations.

Against petty restrictions, such as singing etc.

Now: young workers of [Eccles] to all, whether you’ve been rambling before or not, we extend a hearty welcome. If you’ve not been rambling before, start now; you don’t know what you’ve missed. Roll up on Sunday morning and once with us, for the best day out you’ve ever had.

Scenes photographed in Bowden Quarry near Hayfield – the hastily rearranged meeting place in an attempt to shake off gathering police attention – on the day of what history would remember as the Kinder Mass Trespass are extraordinarily vivid, despite their age. One shows a crowd numbering in their hundreds gathering amidst an amphitheatre of fractured rock looking up towards a figure standing on a gritstone plinth and purposefully addressing the crowd. Were he holding a medieval sword aloft it would resemble a scene from an Arthurian saga. According to contemporary accounts, the man on the rock launched into a passionate sermon against trespass laws and access restrictions, and after warning the crowd against using violence against whatever they encountered, presumably signed off with something stirring like, ‘Right lads, let’s go for a bloody walk.’ And off they went.

Five hundred people left Hayfield that morning, aiming for William Clough, a comely valley that ascends onto the Kinder plateau – the moorland for which the Mass Trespass was destined. It was here that the group met their opponents, a group of gamekeepers who had been specially drafted in for the day by the Duke of Devonshire, who had caught wind of the ramblers’ plans. Violence ensued. We’re not talking wanton bloodshed and rambling-crazed savagery (the most serious injury reported by the Manchester Guardian that afternoon was a keeper named ‘Mr E. Beaver, who was knocked unconscious and damaged his ankle’), but by the time the ramblers reached the plateau – there greeted enthusiastically by another group who had set off from the south – and retraced their steps back to Hayfield, the authorities had decided the landowners’ strife warranted some official fuss.

Assisted by several gamekeepers, the police arrested six ramblers, all aged between 19 and 23: John Anderson, Jud Clyne, Tona Gillett, Harry Mendel, David Nussbaum and the man on the quarry plinth – a 20-year-old, five-foot Manchester communist named Bernard Rothman.

‘Benny’ Rothman was actually not intended to be the rallying speaker at Hayfield Quarry – the original nominee grew meek when the crowd swelled beyond 200 – but the articulate sermon he delivered castigating official rambling organisations for their malaise stirred the crowd into a strident buzz, and Rothman soon became a figurehead for the respect (and the flak) the Trespass would later attract.

Something of a part-time political agitator, the event had been Rothman’s idea. He was a regular visitor to the Clarion Café on Manchester’s Market Street – a kind of informal parliament for the working class and frequently the scene of stylised political debates between socialists, Trotskyists, communists and supporters of other ideologies. Rothman became a member of the BWSF and took part in many of the weekend camps the group organised in Derbyshire, which would invariably draw unemployed young men, many wearing old First World War surplus kit. Following a scuffle with some gamekeepers on the nearby hill of Bleaklow some weeks earlier, Rothman observed that whilst it was not unusual for small groups of ramblers to be beaten ‘very, very badly’ by the gamekeepers with no rebuke, if there were 40 or 50 ramblers the balance would be tipped. Discussing what they viewed as the historical ‘theft’ of the moorland, the plan was hatched for the Trespass.

The main headline on the following morning’s Daily Dispatch read ‘Mass Trespass Arrests on Kinder Scout: Free Fight with Gamekeepers on Mountain’.

Rothman and his five companions were brought to trial at Derby Assizes on the charge of riotous assembly, assault and incitement. Tellingly, as regards the motives of the prosecutors, ‘trespass’ – seemingly the most obvious offence – was absent from the charge sheet, as it was a civil matter. By most accounts the trial was a farce; gamekeepers, members of the police and representatives of the Stockport Corporation Water Works, which owned and leased some of the Kinder Plateau for shooting, delivered overwrought testimonies to a jury comprised largely of the rural Establishment. Whiffs of political perversion in the communist leanings of many of the key figures,* (#ulink_cfd99fd3-5033-537d-a153-06d086133a24) as well as a bit of tokenistic anti-Semitism (the judge made the useful closing observation that several of the defendants were ‘obviously Jewish’), seemed to pervade the proceedings.

Rothman delivered another impassioned speech. ‘We ramblers, after a hard week’s work, and life in smoky towns and cities, go out rambling on weekends for relaxation, for a breath of fresh air, and for a little sunshine. And we find when we go out that the finest rambling country is closed to us,’ he said, before emphasising that ‘our request, or demand, for access to all peaks and uncultivated moorland is nothing unreasonable.’ The six men all pleaded not guilty; all but one were found guilty, and sent to prison for between two and four months, with the harshest sentence – predictably – given to Rothman himself.

It was a huge misjudgement. Far from putting down such actions, the convictions dished out to the Kinder trespassers further ignited the cause. The public response had repercussions still felt today; in many respects, the treatment of Rothman and his cohorts was really the best thing that could have happened to wild places. A rally in Castleton a few weeks after the trial was attended by 10,000 people. In 1935 the Ramblers Association was founded, and a year later the Standing Committee for National Parks was formed, publishing a paper titled The Case for National Parks in Great Britain in 1938.

A setback came in 1939 when the progressively intended Access to Mountains Act was passed by Parliament in such an aggressively edited form it actually sided with the landowners, and made some forms of trespassing a criminal as opposed to a civil offence. But opposition to draconian access restrictions continued, and in 1945 – just as soldiers were returning home from the war to a country undergoing profound social changes – architect and secretary of the Standing Committee on National Parks John Dower produced a report containing the definition of what a national park in England and Wales might be like. Given what went before – and what would follow – it’s worth quoting at length.

An extensive area of beautiful and relatively wild country in which … (a) the characteristic landscape beauty is strictly preserved, (b) access and facilities for public open-air enjoyment are amply provided, (c) wild-life and buildings and places of architectural and historical interest are suitably protected, whilst (d) established farming use is effectively maintained.

In 1947, Sir Arthur Hobhouse was appointed chair of the newly enshrined National Parks Committee, and proposed twelve areas of the UK that would be suitable locations for a national park. ‘The essential requirements of a National Park are that it should have great natural beauty, a high value for open-air recreation and substantial continuous extent,’ he decreed in his report of that year. ‘Further, the distribution of selected areas should as far as practicable be such that at least one of them is quickly accessible from each of the main centres of population in England and Wales.’

In 1949 the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act was passed, and on 17 April 1951 – with an irony not lost on many of the Trespass participants – the Peak District, including Kinder Scout, became the first national park in Britain.

The Lake District, home to the highest mountains in England, followed on 9 May; Snowdonia, thick with legend and shattered geological grandeur, on 18 October; the Brecon Beacons National Park – where I was now being battered – was opened on 17 April 1957, six years to the day since the first, and itself the tenth national park to be opened in England and Wales. Somewhat slower on the uptake, Scotland opened its first national park in 2002 (Loch Lomond and the Trossachs), with the Cairngorms National Park following suit the next year.

For the first time, access to our high and wild places was gilded by law. By 1957, with the opening of the Brecon Beacons National Park, 13,746 square kilometres of the most arrestingly beautiful countryside was officially enshrined as national park – just under 9 per cent of the total area of England and Wales.

The golden ticket in the eyes of access campaigners, however, was not stamped until the turn of the 21st century. The national parks were a giant leap forward, but much of what truly lay open to free access was only the very highest land, where agriculture was poor. Other than areas owned by bodies such as the National Trust, access agreements still had to be reached with landowners concerning the often restrictive rights of way through their land. But in 2000 the Countryside and Rights of Way Act (CRoW) was passed, coming into effect five years later, providing ‘a new right of public access on foot to areas of open land comprising mountain, moor, heath, down, and registered common land’. In other words, the balance had finally swung to the benefit of walkers, who could now roam freely in open country – the inverse to the Enclosure Acts of the 1800s that ramblers had fought so hard to repeal. In a stroke, the area of land upon which a walker could freely roam had expanded by a third.

Benny Rothman lived to see the CRoW Act passed. After a lifetime of lending his voice to access causes, the passing of the act was a vindication that came just two years shy of the 70th anniversary of the Kinder Scout Trespass. This he did not live to see; he died aged 90 just a few months before it, in January 2002.

Had he been at the anniversary celebrations he would have witnessed a fitting endstop, when the current Duke of Devonshire – grandson of the man who unleashed his gamekeepers on the trespassers of 1932, and evidently something of a good sport – took the podium. Presumably with a quiver in his voice, he addressed the crowd thus:

I am aware that I represent the villain of the piece this afternoon. But over the last 70 years times have changed and it gives me enormous pleasure to welcome walkers to my estate today. The trespass was a great shaming event on my family and the sentences handed down were appalling. But out of great evil can come great good. The trespass was the first event in the whole movement of access to the countryside – and the creation of our national parks.

Whether or not the national parks would exist today without the Trespass – and whether I’d be able to appreciate the feeling of gradually being ripped from my feet on the top of the Black Mountain in the chilly spring air – we cannot know. But what is clear is that access to the British countryside took a great leap forward that day in 1932, and the degree of freedom we can all now enjoy wasn’t easily won.

However grumpy I was feeling in the summit shelter atop the Black Mountain, I was glad to have made it. Now all I had to do was make it back to the car. Emerging from the shelter, I caught sight of the trig point – a slim concrete pillar found on many British summits, for reasons detailed later – twenty metres or so away. Staggering over and touching the top, I snapped an awful summit photograph and, with no small degree of haste, turned in the direction from which I’d come.