По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

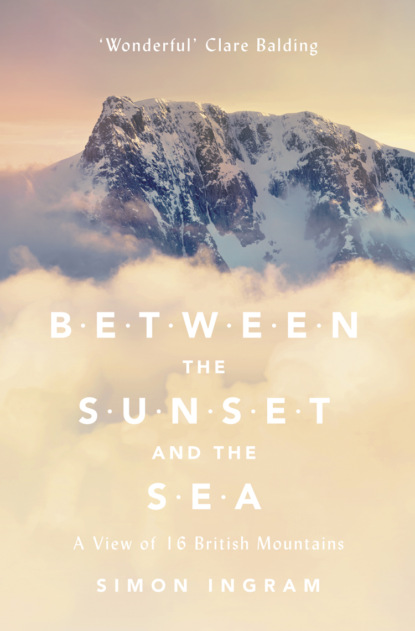

Between the Sunset and the Sea: A View of 16 British Mountains

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

I didn’t have time to do the Munros, even if I wanted to. I certainly couldn’t do all the Corbetts, or even the Wainwrights. I admired and envied the experiences of all those who did, but I couldn’t invest the precious time I had to spend in the mountains to one geographical area, and certainly not to the same narrow band of the vertical scale.

Stand on Beinn Dearg’s summit, make a little indentation in your thigh, and take a moment to consider your context – there’s the Atlantic, there’s the river, wriggling along far below, and here you are, alone amongst it – and you’ll realise how little numbers matter when it comes to climbing mountains. Beinn Dearg is a mountain: each and every one of its 35,970 inches builds towards a top of such elevated spectacle, you’d be mad to discount it on any basis, let alone it not making the coveted slate of a man whose life occupied but a flash of its own existence.

I looked at my watch. Six p.m. It had taken far more time than I’d thought to reach the summit and darkness would soon start falling. Cloud was beginning to mither the higher tops, and was creeping up the gullies and valleys around me. Walking out would take hours. Time I got down.

Taking a last look around, I walked south from the summit cairn, intending to follow Beinn Dearg’s skyline as it curved around to the east, then find a comely slope to descend into the valley once the mountain had surrendered most of its height.

Ahead of me, the edge of the summit appeared as a hard line against the sky, like the side of a flat roof or the end of a diving board. I wasn’t alarmed: the convex slopes that built these mountains meant that easy terrain beyond – a broad series of rock steps, or a thin path negotiating a steep slope – would emerge as I got closer.

Only it didn’t. I reached the edge of the summit plateau and froze. For the first time I saw the descent route, and it was a shock. Ahead of me and below was a thin sail of brown, bitten rock. Curved slightly, its outside edge was completely vertical in its fall to the valley floor, whilst the right side – now filling with rising cloud – had a steeply tilting grassy ledge across which a thin path beetled. Beneath that, a crag, then a drop of similar horror. From the top of the mountain down to the first bit of buttress-cut slope was probably in the order of 500 metres. That was the only way the mountain went. I’d two choices: climb the crest on good rock but over big exposure, or traverse the grassy ledge and pray it wasn’t slippery. My company on both of these options would be open intimacy with a drop as high and as vertical as the Empire State Building. I didn’t remember this! And this wasn’t even the most pressing problem.

At my feet – far from an easy toddle down a few amenably angled rocks – was a vertical step of about three metres. Its bottom was a little platform of rock, on either side of which the mountain fell away with fatal steepness. To get to it required a down-climb as if on a very steeply raked ladder, only with tilted footholds of wet rock instead of rungs, with no guarantees of integrity and no margin for error at the bottom. Piece of cake.

I pulled out the map and looked at it helplessly. I’d no phone reception, and no rope – ropes are not necessary to reach the top of all but a few major mountain summits in Britain,* (#ulink_3701634b-a406-523d-8d3d-3d3e74bd4694) and next to useless unless you have someone with you. This was the way off; the only other option was to go back the way I came, and I didn’t fancy that either. With increasing alarm, I looked around at the clouds and tried to rationalise. The down-climb in front of me looked delicate, but achievable. I must have done it before, though probably under direction and encouragement – and with even a helping hand – from Tom. But I had done it. And confidence was two-thirds of the battle. As long as I didn’t lose my cool I could do it. Just a few feet of down-climbing and a bit of exposure, and I could be on my way to a meal and a bed. Either that, or I’d just have to learn to live up here.

Descents like this are what fatal-accident statistics are made of. Coming down mountains claims more people than going up by a ratio of about 3 to 1. What was worse, I really hadn’t expected this. By ploughing up the hill, waving my previous experience of the mountain as a tool which, as we’ve seen, turned out to be less than reliable, I’d neglected to do enough research. A failure. But a lesson, too – and one I could learn from provided I could safely find a way out of this jam.

Mustering confidence, I fixed my mind on something random. I’d read somewhere that reciting your telephone number backwards during times of fear engaged a part of the brain that antagonistically quelled your fright cells; as I turned to face the rock and placed my foot on the first ledge a few feet down the crack, I shakily began to do it. Three points of contact at all times; look after your hands, and your feet will look after themselves. I could smell the murk of the rock as I pushed my face close to it, trying hard to make my entire world the crack before me and the narrow tube of rock at my feet I had to get down. No mountain, no drop – just this little ladder. Nothing else.

Concentrating on moving my hands to where my feet were, striking the rocks with the edge of my fist to check their stability, and mumbling my reverse phone number aloud with my exhales, I steadily made progress down the crack. I dropped down the last foot, landing squarely on the little platform. My heart audible in my ears, I took a deep breath and continued on down the ridge, not wanting to lose momentum until these dangers were passed.

I rejected the crest of the precarious rocky sail in favour of the lower grassy terrace, moving to the right of the ridge’s frightening-looking apex. Trying to move as smoothly as I could, I traced the skinny path with my eyes then followed it with my feet, taking care – great care – not to trip. Writhing cloud had now clogged the void to the right, momentarily taking away the psychological impact of the drop. It parted as I approached the end, and I caught the glint of the river far below and the edge of Beinn Dearg’s mighty south-west buttress. There it was: that memory, that feeling of height – the kind of feeling that hits you like a nine-iron to the back of the legs. It was exactly what I didn’t need at that precise moment, but I stayed focused for the last few feet of the traverse. Then suddenly it was over. I scrabbled over a few rocks onto a little ledge, and when I saw that the mountain was considerably tamer from here on and that there were no more surprises in store, I let out an audible groan of relief, crumpling against the rock, my legs buzzing, arms shaking, breathing rapidly. That had been unexpectedly hairy.

Although I wasn’t off yet and the descent was still going to be difficult, I now knew that I was going to get down. After that, dinner was going to taste particularly good. I might even have an extra beer to celebrate being able to have an extra beer.

But this was only the first. As it would go, fifteen more mountains lay ahead – each with its own challenge, its own particular conditions, feel and story to tell. Beinn Dearg wasn’t the hardest. It also wasn’t the highest. But for me this was the mountain I’d always associate with this feeling of height; of that elevated perspective you can only get from a mountain, and of the exhilaration and the fear that grips you by the stomach – the basic elements that make these places so special. In 1911 the Scottish-American naturalist John Muir wrote that ‘Nature, as a poet … becomes more and more visible the farther and higher we go; for the mountains are fountains: beginning places, however related to sources beyond mortal ken.’

I rose, and as I did so I pushed my wet hair out of my face and felt a substantial deposit of sharp sandstone grit upon my forehead. Confused for a moment, I realised my hands had picked it up off the rock and I’d wiped it onto my brow every time I’d mopped it. I was literally sweating grit.

My eyes followed the rock at my feet up towards the ridge I’d just climbed. The stuff I was carrying down the mountain on my forehead, these mountains are made of it. That brown, course-grained sandstone is even named after the area best exhibiting it: Torridonian sandstone, they call it. The whole range has rocks made of this grit as their bedrock. It’s why Beinn Dearg is called Beinn Dearg: for the way the sun lights the brown sandstone and deepens it to red in the westerly glow of sunset. It’s famous for this.

But nobody ever tells you about the lichen. Brilliant white whorls of it, augmenting almost every rock. Unless you were on the hill you wouldn’t see it or know it was here. But up on the ridge it’s everywhere. It looks as if the mountain is pinned with white rosettes; silly little patches of prettiness adorning its hard skin.

* (#ulink_e3cb68f0-edd9-5c6b-9c5b-b7febfeb9721) Which was of course said by ill-fated climber George Mallory at a lecture in 1923 when asked, ‘Why climb Everest?’ Nobody really knows what he meant, or even if he said exactly this; it could have been something profound, or it might simply have been irritation at the question. Either way, it has passed into history as the most famous three-word justification of the ostensibly pointless.

* (#ulink_809496a8-c749-5287-a889-647279549092) Most famously, Sgùrr Dearg’s notorious ‘Inaccessible Pinnacle’ on the Isle of Skye. There are other summits in Britain – indeed, more on Skye – that require the use of a rope, and ability is of course subjective, but there are ways up most of our principal mountains without additional aid, certainly in summer.

PART I (#udee40a0e-8cb7-58c9-997d-92b4924499db)

SPRING

2 SPACE (#udee40a0e-8cb7-58c9-997d-92b4924499db)

It was May, and southern Britain was drowning. Winter had been hard, and spring hesitant to commit in its wake. The last six weeks had seen new lambs arrive along with the first, anaemic, blush of colour to the landscape; both were soon buried in snowdrifts. For mountain climbing, this didn’t bode well. Whilst such seasonal false starts were happening so dramatically in the valleys, the weather on the tops would be even more alarmingly fickle.

Six months after I returned from Torridon the thaw finally came – and with it rain, on a seemingly biblical scale. It was in between two of these May downpours that I went out to the garage to resume packing the bag I intended to take on the journey of sorts that, with the albeit damp foundations of spring firmly bedded, could now begin.

One of the most important aspects of this journey was my desire to see the mountains at their most wild, and experience their most extreme and dynamic moods. Happily, these conditions occurred every 24 hours without fail, and twice: sunrise and sunset. To really know a mountain you need to see it in all shades of the day and, preferably, at night – and in the high places of Britain contrasts are magnified far more than at sea level. A mountain feels intense and quite different in the dark. My plan, therefore, was to climb as many as I could at the frayed ends of the day, the time when the mountains lose the little civility they tolerate during the daylight and return to the wild. Where I could I’d sleep on them, drink from their streams, seek shelter amongst them and walk in all weathers. And whilst I’m not saying that I didn’t want to do the living-off-the-land thing and wander in with a stick, a cloak and a big knife (well, maybe I am), I was going in to enjoy the mountains, not survive them. But that still meant that a certain amount of kit was necessary.

It started out as a small bag; just the ascetic essentials for safety and warmth, crammed into a small rucksack that was light enough not to be an onerous burden, but fortified with enough to see me through any blip in the notoriously shifty mountain weather. I wanted it to be there, ready and packed – something I could stash in the car boot for deployment at any opportunity. As time passed, however, and I watched all manner of winter weather scrape by the window, additions inevitably began to creep in: another jacket, an extra pair of gloves, a second hat, my spare compass, the emergency map. There was, when walking at the extreme ends of the day, always the possibility of becoming cold or lost: and, as wild camping was on the cards, a tent – or bivvy bag, if I was feeling intrepid – a sleeping bag and a roll-mat needed to go in there, too. Now there was far too much for a little rucksack and so a larger rucksack was needed. And so on.

It’s easy to get excited about outdoor kit. The shops that sell it are little pieces of the mountains dropped into urbania; boutiques filled with shiny, purposefully robust equipment destined to become muddy and tarnished. It’s no problem at all to disappear into these places for ages. Inside, you can appraisingly touch the latest waterproof fabrics, assess the tents packed into tight nylon sausages for weight, gaze at the newest boots, and wonder what it might be like to have it all at your disposal. You’ll recoil at the price tag, but over the coming weeks you’ll come to realise that you not only want this piece of equipment but categorically need it. Every hobby has its own infectiously fetishistic side, and climbing mountains is no different. There’s something slightly gladiatorial about it; layering up with stiff, rugged fabrics and packing everything on your back that you need to self-sustain in a wild environment is a pleasing feeling. But aside from the pomp, drastic financial outlays and painful colour clashes, dressing properly is also absolutely necessary. You need to not only be warm and dry, but comfortable under considerable physical strain. It gets pretty tough out there.

I was fairly sure I was in possession of everything I needed for whatever I was about to face; the problem with our seesawing climate was knowing exactly what that was likely to be. Eventually I gave up on trying to pack the perfect bag and instead lugged the now considerable pile of clothing and kit in various states of garage-induced mustiness to the car boot. Most of it would remain there for almost a year and less than half of it would get used. But as I packed the last pieces in, it was empowering to think that I’d be comprehensively covered should I be seized at any moment by the notion to turn north in search of mountains. You can choose your cliché. To get away from it all. Escape the rat race. To get some headspace. For many who habitually head for the high, wild places, this idea of space, of solitude, is a key part of the appeal. For many, it’s the whole point.

Of the many things you get used to hearing when you live in Britain – the moans about the weather, the speed at which the government of the day is sending the country to hell on a skillet and the fact that petrol isn’t as cheap as it used to be – one gripe that’s particularly difficult to escape is how hopelessly, intolerably crowded the country is. It would be easy for an outsider to visualise Britain as a kind of unstable skiff of disgruntled, over-jostled passengers that at any moment will crack loudly and spectacularly discharge its contents into the North Atlantic. But in practice this preconception is really complete nonsense.

The next time you find yourself travelling long distance across the country, allow yourself for a moment to be struck by just how physically empty much of Britain is. We’re not talking boundless, unmolested wilderness exactly; just space. Leave London by car in most directions and minutes after you’re outside the M25, the number of buildings falls away and you’re amidst the most bewitching countryside. Even in the industrial north – where, if maps were to be believed, cities seem to spill into each other in an arc that starts at Liverpool and doesn’t really stop until Leeds – there are huge expanses of not an awful lot. There doesn’t seem to be anything sizeable at all between Lancaster and Whitby (the span of the entire country) except high, savage moorland; ditto between Carlisle and Berwick, and Newcastle and Penrith. Of course this is difficult to appreciate from King’s Cross or central Birmingham. And on the face of it, the numbers do disagree.

According to the 2011 census, 56,075,912 people live in England and Wales. This equates to just under 371 souls packed into every one of a combined 151,174 square kilometres. That’s a lot. But that’s also presuming they’re spread uniformly, which of course they’re not. The 70 most populous towns and cities in England and Wales cover a total of 7,781 square kilometres – around 5 per cent of the two countries’ total area. Into that a staggering 60 per cent of the population is shoehorned. A total of 33,899,733 people live in one of these built-up areas, which means the average population density of the remaining 95 per cent of the country exhales to a rather more spacious 154 people per square kilometre. This is a third of England and Wales’ ‘official’ population-density figure, but again in practice this is a rather misleading measure as the remaining population is also by no means evenly spread, being instead compartmentalised even more by the many thousand smaller clumps of population: big towns, small towns, villages and so on.

Scotland belongs in a different class altogether. Covering 78,387 square kilometres and home to 5,313,600 people, its average population density of 67 people per square kilometre drops to a decidedly thin 37 when the ten largest settlements – which cover just 769 square kilometres, or a fraction under 0.9 per cent of Scotland’s total area – are disregarded. So really, when you think about it, Britain consists of a small amount of space in which a huge amount of people live, and quite a lot of space where relatively few people live.

Mountains are the unconquerables. They are, in every sense, the last frontier of Britain – and its emptiest places. By their very nature, they will be the last bulwarks to be overcome by the rising flood of population and development that the gloom-mongers tell us is relentlessly on its way. Inhospitable and extreme, they’ll become refuges for those seeking escape; pointy little islands of silence and space, too awkward to be developed, too inconvenient to be home.

Of course, for those who crave calm, said solitude and escape from the very real crowding of cities, the mountains are refuges already. They’re the greatest empty spaces in a country of otherwise relatively lean dimensions. Consequently, I was keen to find a mountain that might demonstrate exactly this, a wilderness close to something, but bare of anything; a kind of accessible antithesis to claustrophobia.

I spent some time trying to find it. It needed to be a place where you could feel like the only person in existence, where the landscape around you is so limitless and free of human meddling it has the potential to redefine perspective and blow any sense of claustrophobia or overcrowding out of the system. The trouble was – and this was a happy dilemma – there seemed to be too many places to choose from.

Arthur’s Seat, standing above the spired city of Edinburgh like a spook over a child’s bed, stood at one extreme, given its striking juxtaposition of the brimming and the barren. Such is the intimacy with which the city and the peak nuzzle up against each other you could honk a horn or even open a tub of particularly delicious soup in the city and someone up on Arthur’s Seat would notice. Not just that, the visual contrast was particularly unsubtle. The roots of a long-dead volcano hewn and squashed into its present form by glaciation during the Carboniferous period some 300 million years ago, its bold profile grinning with crags made for a strikingly bare companion to the twinkly steeples and townhouses of Edinburgh. But at 251 metres it’s tiny even by British standards, and didn’t so much offer an escape from civilisation as stand proud as a podium amidst it – somewhere to gaze from a pleasing point of observation down upon the city, but never to feel truly removed from it.

Dartmoor, in the south-west of England, seemed to offer almost limitless desolation with a pleasingly eerie footnote, thick as it is with folk legend and weird, gaunt tors. Much of it sits at around 500 metres above sea level, making it surprisingly elevated for a moor; look north from its highest point at 621 metres and the next comparably lofty ground in England doesn’t crop up until Derbyshire. But a quarter of the national park – and around half of the area you would call the ‘high’ moor – is used by the Ministry of Defence, who, for a few hours most days bounce around on it in jeeps and shoot at each other with rocket launchers and other noisy things entirely unfavourable to tranquillity. To give them their due, the military look after the moor rather well in the moments they aren’t using it as a kind of Devonshire Ypres. But to me, the process of having to check access times on a website to avoid the slim possibility of being shot – or inadvertently stepping on something that might cause me to be returned home in a carrier bag – sort of defeated the object.

My search area was beginning to spiral northwards again when a news story caught my eye. Suddenly the answer was obvious, and a decision was quickly made. And fortuitously enough, the solution to this quest for space came in the form of space – albeit space of a quite different kind.

Whilst the most obvious menace with the potential to collectively rob us of quality elbow room and the balm of tranquillity is hustle and bustle, cars, noise and overcrowding, it appears there’s another, more insidious, space thief at work in Britain. Disruptions of migrating birds, erratic breeding patterns of animals, falling populations of insects and even serious health conditions in humans are being blamed on it. I learned all of this one morning in February during a discussion on the news centred on an area of South Wales that had just become the fifth area in the world to be selected as an International Dark Sky Reserve. What this meant was that the quality of the night sky above this particular area was of such superior clarity, free of the sickly orange bleed of large population centres and their streetlights, that it not only warranted recognition, but also protection. The area was the National Park of the Brecon Beacons. The Brecon Beacons are mountains.

It made perfect sense. Where there are people there’s light, and therefore where there’s light, you can never truly be away from people or their influences. But there’s also light where there are only people some of the time: roads, warehouses, industry, infrastructure. Subtle though it is, understanding this relationship between human-manufactured light and the night sky will lead you to the emptiest parts of Britain.

During idle moments over the next few weeks I learned some interesting things about light pollution. I learned that light that falls away from the area where it’s needed or wanted is called ‘stray light’ and an unwanted invasion of this – be it a washed-out night sky with stars lost to the amber haze of a nearby town or the clumsily angled floodlight on your neighbours’ wall that lights up your bedroom like an atomic flash every time a cat walks under it – is given the apt term ‘light trespass’. Lighting used to throw dramatic illumination on a building or object is called ‘accent lighting’, and I also learned that all of these are in general bad news to lovers of dark skies and given the neat collective term ‘night blight’. One of the worst-afflicted places on the planet is Tsim Sha Tsui in Hong Kong, where the level of light has over 1,200 times the value defined as the international standard for a dark sky.* (#ulink_5871fb58-8024-50ca-95c9-913a8d9714f1) The facility where this is measured is, with unfortunate irony, the Space Museum. I also learned – thanks to a charming organisation called the International Dark Sky Association – that an unspoiled sky is visually packed with stars right down to the horizon and the starlight is strong enough to cast noticeable shadows on land. In such conditions, picking out individual constellations is almost impossible to the untrained eye given their sheer abundance above.

I also learned that, perhaps surprisingly, Britain has some of the largest areas of dark sky in Europe. This was illustrated by a natty map of the United Kingdom as if seen from space, with clumps of heat-signature colour spread over the country like an outbreak of digital pox. The largest population centres – London, Liverpool and Manchester, Birmingham and Glasgow – were coloured an angry red, surrounded by a scab of yellow, gradually fading into pale blue. The areas of least pollution were deep navy, tonally seamless with the sea. On land, the places where these were darkest and most extensive were the mountains. Scotland blended with the sea just north of Stirling. The Pennines, the Southern Uplands of Scotland, the moors of the south-west, and the Lake District were all dark – as were blanket swathes of Wales.

The population-density maps had been one thing, but I hadn’t seen anything quite so starkly illustrative of this idea of mountain ranges as islands – or voids – amidst British civilisation. This map cut through the intricate camouflage of daylight, highlighting human intrusion like phosphorescence in a murky lake: a true map of British space. And a week into May, with my eye on the weather I picked the best of a bad bunch of moonless days and headed for South Wales, to spend the night on top of the mountain – all being well – that lay beneath some of the darkest, most spacious skies on the continent.

The mountains of the Brecon Beacons – like most British mountains – are totally unique. The name rather evocatively comes from the signal fires once lit on their summits to warn of approaching English raiders. But whilst many other mountains wear the suffix of ‘Beacon’ across the land, none is quite like the Beacons of Brecon. None is even a bit like them.

Such is the ancient, much-brutalised geology of the British Isles, that every bit of land sticking its neck up has been battered by a particular something, in a particular manner, at a particular point on its long journey, marking it as different to mountains not that distant from it. That’s why British mountains have long been of interest to geologists: they are some of the most scrawled-on and kicked-about creations nature has ever sculpted, and they wear these signatures like scars.

The Beacons are a perfect case in point. From a distance, as you approach from the direction of south-west England, their character is clearly seen. They look like they’ve been finely carved from wood by a carpenter with an eye for nautical lines; all elegant scoops, gorgeously concave faces and wedged prows, a natural symmetry that seems somehow too symmetrical to be natural. These ingredients rise, gently but inexorably steepening towards the 900-metre contour line, whereupon they are abruptly sliced flat, as if by plane and spirit level. Their characteristic form is best demonstrated by the highest massif – the ‘Brecon Beacons’ themselves, the central trio of Pen y Fan, Cribyn and Corn Du – but all of these startling mountains display the same touch. The other visible hallmark is their cladding: these are not cragged and hard-skinned like the mountains of Glen Coe or Torridon, or even Snowdonia. All have coats of horizontally ridged green corduroy, the edges of which catch the first winter snows and hold the last, striping the mountains white. Where paths have worn through, the mountains beneath bleed sandstone a vivid, Martian red. The flat ‘billiard’ tops exhibited by the most distinctive of these mountains are the remnants of ‘plateau beds’ – a much grittier, harder sedimentary layer that has been chewed into the air by weathering, then resisted further attack. If the mountains look as if they’ve been cut flat it’s because, in a manner of speaking, they have.

These central mountains are the most frequently climbed of the Brecon Beacons, and are rewarding and accessible to all. The drops are huge, the views immense, the sense of achievement fulfilling and the aesthetic tremendous. But it wasn’t Pen y Fan I was here to climb. At each of the park’s extremes lie two ranges that confusingly share the promising (promising if you’re in search of a lovely dark night sky, anyway) name of Black Mountain. Well, they almost share it: the Welsh names for each reveal the subtlety lost in their English translation. One lies close to the English border in the east, and is a high but inauspicious collection of moorland summits bearing the collective name the Black Mountains (Y Mynyddoedd Duon). The other, on the park’s spacious western fringes, bears the singular denotation the Black Mountain (Mynydd Du), and this one most definitely earns its chops in the spectacle stakes. Burly and remote, its summits are in fact the hoisted edges of an enormous, wedge-shaped escarpment, tilted into the ocean of moorland like a sinking liner.

The more specific names associated with this mountain and its features are rather bewildering, and you may have to bear with me here. Mountain toponymy – as we will continue to see anon – is not an exact science, and is often inconsistent across a relatively short distance. A summit in South Wales (Fan, Ban, Bannau, Pen) isn’t necessarily a summit in North Wales (Carnedd, Moel), although in both places a llyn does tend to be a lake, cwm a valley, craig a crag, bwlch a pass, and fach and fawr little and large, respectively. The Black Mountain as a massif is Mynydd Du; the long escarpment of the eastern flank is given the name Fan Hir, fan meaning crest. But fan can also mean peak – and there are two of these on the Black Mountain, three if you count Bannau Sir Gaer, which uses the term bannau, which is probably derived from ban, which is in turn the plural of fan. Bannau Sir Gaer means the ‘Carmarthenshire Beacon’, and this is often still known by its mixed translation Carmarthen Van, van being yet another variant of fan. Fan Foel is one summit, probably meaning ‘bald peak’; Fan Brycheiniog is the other, named after the small kingdom to which the mountain belonged in the Middle Ages. Like I said, bewildering. But if you take anything from this, make it simply the following: mountain names can be complicated. And it was remote Fan Brycheiniog – at 802 metres the highest point of the Black Mountain – that was to be my mountain of space.

The weather was, it has to be said, not good at all. The rain held off long enough for me to enjoy the sinuous roads over the border and the tentatively awakening villages and pubs as I approached Brecon. It even stayed clear enough to appreciate the tall, distinctively clipped top of Pen y Fan as I passed Brecon and headed for the empty western part of the national park. A few miles outside a little place called Trecastle, a left turn led into a long valley of arched hillsides and naked, wintered trees. The road dwindled to such a degree that I began to suspect it led nowhere, and indeed it proved more or less to do just this. It first climbed, then dropped into a scraped landscape of wide-open moorland. This was one of the barest landscapes south of Scotland. And to the west, far away across it, there it was.

The Black Mountain filled the horizon like a wall. Though it was smudged by cloud, I could just about see the top reaches, for the moment at least. I certainly wasn’t going to be reclining under an umbrella of stars tonight, that was for sure; although I’d brought a tent, my optimism of a clear night out atop the mountain had faded with every squeak of the windscreen wiper. More concerning was the wind; I could feel it whumping into the car as I sat gazing out at the grey landscape, and by the rate the weather was moving across it, things would only get rougher higher up. Trouble was, whilst camping probably wasn’t an option, it would inevitably be night in a few hours. Whether I liked it or not – and regardless of whether the weather improved – I’d definitely be coming down in the dark.